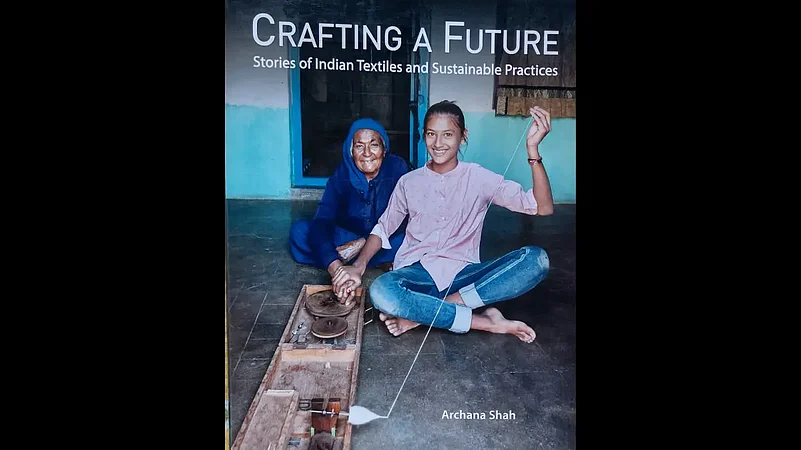

To study the diversity and true value of India’s handcrafted textiles, Archana Shah – an alumnus of India’s prestigious National Institute of Design (NID) and the founder of the eco-friendly clothing brand Bandhej – travels throughout the length and breadth of the country. ‘Crafting A Future – Stories of Indian Textiles and Sustainable Practices’ is an outcome of her many travels and interactions with the artisans.

According to her, a handloom product has to be interesting enough to attract the consumer. “The handloom sector, if managed properly, can generate millions of dignified work opportunities, even eliminate the need to build one large industry at times. But the consumer will not buy a product because you are creating jobs. They will buy it because they like it. So it is necessary to ensure that fabrics are special and of good quality to justify the minor price difference between mechanised production and unique, handcrafted textiles,” she said

The Hyderabad-based Malkha project was started in 2003 by Uzramma, a handloom revivalist who had earlier initiated the Dastkar Andhra Trust in 1995. Malkha derives its name from a combination of the first three letters of the words 'malmal' and 'khadi'. According to Uzramma, ‘the vision was to put the whole cotton cloth-making chain back in the hands of the people who did the work, and to make a complete chain of cotton growing, cloth making and local markets.’ The Malkha process explores technology that responds to the needs of the primary producers, does away with unnecessary and wasteful processes in its journey from plant to cloth, is ecologically sensible and least damaging to the intrinsic properties of cotton. Malkha is pure cotton cloth made using the raw cotton that grows in the vicinity, and it stands for a decentralised, sustainable, field-to-fabric cotton textile chain, collectively owned and managed by the primary producers, the farmers, ginners, spinners, dyers and weavers. Small-scale spinning units have been established near the cotton growing regions to save on transportation.

***

The move away from baling cotton was at the heart of the Malkha project. Although weavers in villages are surrounded by raw cotton, they almost always have to get their cotton yarn from spinning mills located miles away. Farmers too face a similar problem; there are handloom weavers all around them, but they end up selling their raw cotton to ginning mills, which then sell pressed bales of cotton to distant spinning mills. The cotton thus travels from the village all the way to the spinning mills for conversion into yarn, and then travels back to the weavers in the villages. If the raw cotton produced in the village could be converted into yarn locally, both farmers and weavers would benefit greatly. Moving away from baling and un-baling also helps preserve the inherent qualities and lustre of the lint.

Uzramma’s vision and the technological inputs of L. Kannan, a graduate from IIT Madras, have made Malkha’s small-scale energy saving approach possible. The first step was the setting up of a small spinning unit at Chirala, close to the cotton-growing region. Once this proved successful, the Chirala model was replicated at eight cotton growing locations in Andhra, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. The Decentralised Cotton Yarn (DCY) project is funded by the Ministry of Rural Development through the National Institute of Rural Development. Today there are six units producing Malkha yarn, spread across the four states, Chirala, Khammam and Karimnagar in Andhra Pradesh, Bellary in Karnataka, Wardha in Maharashtra and Balrampuram in Kerala, which is run entirely by women.

Malkha spinning is different from conventional spinning; it saves the lint from the damaging process of baling and un-baling. This saves valuable energy, and allows the yarn to retain the absorbency, bounce and lustre that is natural to cotton. Secondly, Malkha yarn making is a small-scale activity, and provides work for people in their own neighbourhood. The yarn is specifically produced for handlooms, and distributed in hanks that works best for this sector. The slow-speed processing of different stages of handweaving avoids the heat and stress created by mechanised weaving. The handloom sector treats Malkha yarn with respect and ensures that the natural qualities of cotton retained during yarn-making are also preserved in the processes of cloth-making.

The Malkha yarn is delicate as it is not as highly twisted as the mill-made yarn. To strengthen the yarn for the warp, it is treated with starch and oil to make it stiff and smooth enough to withstand the rigour of weaving. Natural starch made from local rice or millets is used for sizing. This is sprayed onto the stretched warp, then brushed with a sizing brush to spread it evenly. The fabric is woven on a handloom, by both men and women. Bamboo or millet stalk reeds are used for the weaving, which are gentler on the yarn than the metal reeds used for mechanised production. They allow the uneven natural slubs in the Malkha yarn to come through in both warp and weft. This gives the fabric its unique tactile quality and the touch and feel of handspun, handwoven khadi fabrics.

Only natural plant-based ingredients are used for dyeing, which causes no environmental pollution. Before they are dyed, the yarns or fabrics are well scoured to remove natural oils, and dipped in a mordant bath, with the exception of indigo, which does not require any mordant. A variety of plant-based products are used to dye the yarn or fabric: Indigofera tinctoria for indigo blue, Acacia catechu for shades of brown, Terminalia chebula (harda) and Punica granatum (pomegranate rind) for yellow, and Onosma echioides (kasimi) for grey, and non-toxic alizarin for red, and the dyers have standardised the processes of colour fastness.

***

The Malkha fabric becomes softer, more absorbent and comfortable to wear with every wash, and has a low carbon footprint. Many designers and high-end retailers working with handcrafted textiles are using this fabric in India and abroad. The fabric is currently exported to Italy, France, Norway, the UK and the USA. This wonderful initiative needs to be expanded to benefit larger sections of farmers, weavers and all artisans involved in this supply chain. It is an eco-friendly means of production with the possibility of preserving indigenous varieties of cotton, which is good for the soil and for the user, preserves the diversity of both raw material and techniques of weaving, and has the potential for creating a large number of jobs within the region. Malkha has become more than a mere quality of cotton fabric. It is fundamentally rooted in scaling up sustainable, eco-friendly formats of processing cotton and yarn, and seeks the ultimate goal of linking producers directly to buyers.

Natural Dye Centre

The Malkha initiative uses only natural dyes for all its cotton fabrics, and for a regular supply of natural-dyed cotton yarn for its weavers, Malkha set up the Natural Dye Centre in 2004 under the guidance of natural-dye experts Chandramauli and Jagada Rajappa, who have trained the staff in the process of natural-dyeing. The centre is located in Hyderabad at the Rural Technology Park on the campus of the National Institute of Rural Development, and today, it is headed by the dye master, M. D. Salim Pasha, who has trained a group of women to do the washing and dyeing.

***

Salim took on the responsibility of setting up a dyeing unit and training women from the surrounding Rajendranagar area who had no previous experience of dyeing. His team of six women has now mastered the art of dyeing around a dozen shades by using colourants such as indigo for blue, non-toxic alizarin for red, pomegranate peels for yellow, ratanjyot (jatropha) for grey, a solution of fermented jaggery and iron for black, pomegranate peel and a solution of fermented jaggery and iron for olive green, catechu for brown and manjistha (madder) for pinks.

Cotton yarn is sent by the Malkha office to the dye centre where it is first boiled in natural soap and soda ash solution to remove the inherent wax coat and impurities for better colour penetration. The hanks are dried, and then, the next day, dyed with myrobalan solution. They are dried and kept for a day or two before they are dipped in alum solution, which acts as a mordant for colour absorption and fastness. The hanks are again dried and left for a few days before they are dyed in the required shade. Only indigo does not need a mordant and the washed hanks are directly dyed in indigo vats. The centre has 40 indigo vats, and these are used in rotation for dyeing the yarn. Indigo blue is one of the most popular colours for Malkha fabrics, so normally, for two hours at the start of the day when water is boiled for the dye baths for other colours, they dye fabrics in indigo, which is a cold process. All other colours use the hot process where the dye bath solution is boiled before the hanks are soaked in the tub. For deeper colours, ounds. They have learnt new skills and have become accomplished dyers. The work is laborious but the women said, ‘Once you get used to the work, it is quite easy and safe as we use only natural ingredients. We have built close friendships at the dye centre and are happy to spend a pleasant day working together.’

Extract from the book Crafting A Future – Stories of Indian Textiles and Sustainable Practices by Archana Shah, published by Niyogi Books.