I am the sum of my books,” said Sir V.S. Naipaul, in the 2001 Nobel lecture, “everything of value about me is in my books.” Yet, the famously irascible author had received news of his Prize in Literature by acknowledging “great tribute” to only “England, my home, and India, the home of my histories”. Despite being honoured specifically for “works that compel us to see the presence of suppressed history” he had conspicuously suppressed Trinidad from his own history, neglected to mention the island of his birth and early upbringing, the setting for five sparkling early novels, and subject of many essays written across six decades.

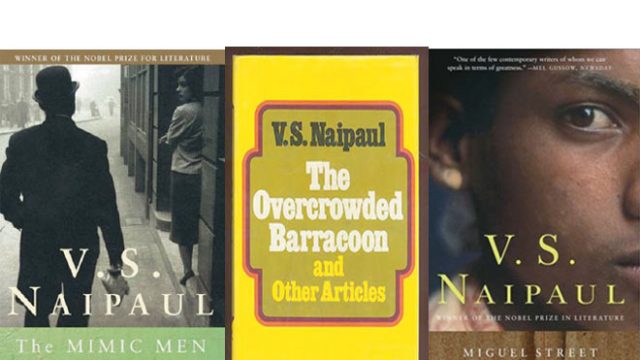

Trinis, as the island’s famously relaxed natives call themselves, weren’t particularly perturbed; they expect it from Naipaul after so many years of carefully calibrated scorn. He’d made his feelings known almost as soon as he’d managed to get away from home. By the time the young writer had pronounced Trinidad “a simple colonial philistine society”, in a 1958 essay included in The Overcrowded Barracoon, it was clear that he was made for bigger challenges. “The only way out” he declared, to despatch the “barrenness” that had beset him, was to head immediately into the larger, unknown, unexplored world.

He was only 26 when he wrote that, but three increasingly mature books into the game, and Naipaul was already making for roads which led everywhere but home. Like the narrator of the beautifully observed miniature universe of Miguel Street, the instinctive young writer trusted the half-perceived portents around him, and walked purposefully towards the unknown, “not looking back, looking only at my shadow before me, a dancing dwarf on the tarmac”.

At the time, it was probably a necessary break; the confining home society abandoned to bring distant horizons within reach. Trinidad is just a squarish little blob of land the size of Goa, marooned in the mouth of the giant Orinoco river, populated by well under a half million people in those years, comprising a somnolent, unabashedly pleasure-seeking society. It’s a place where ‘liming’ (or purposeless, companiable idling) is still a national pastime, where half the population spends half its annual income and most of the year preparing for the spectacular Carnival blow-out that shuts down the entire country for a week.

Trinidad has spectacular beaches fringed with jungle, mud volcanoes and a bubbling lake of pitch, rice-growing marshlands at one limit and wide sugarcane fields in the interior. And it has always been a regional cultural powerhouse— original home of calypso, the steel band, limbo and Indo-Caribbean chutney music, breeding ground for great cricketers, Olympic sprinters and international footballers, motherland of delicious Creole culinary syntheses—but it has never been home to the kind of culture that compels ambitious colonials far from the metropolis. Naipaul was never wholly of Trinidad, merely from there, he did need England and, eventually, India, to properly work out where he needed to go and how to get there.

As he admitted in the Nobel lecture, the breakthrough came with the searing The Mimic Men, a masterful, completely assured, fully developed, portrait of the island culture he had inherited. “In just ten years,” Naipaul said at that Stockholm podium, “my birthplace had altered or developed in my writing: from the comedy of street life to a study of a kind of widespread schizophrenia. What was simple had become complicated.” And with that great novel, he outgrew Trinidad as personal centre of gravity, and headed off to travel the areas of darkness in the world, to steadily pile together the insightful non-fiction that eventually gained million-dollar recognition and the Nobel Prize.