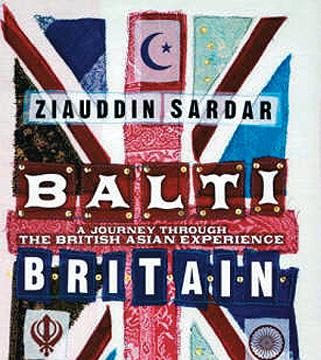

Part-memoir, part-travelogue, part-social, anthropological and pop-culture history, eminent Muslim intellectual Ziauddin Sardar’s account of the South Asian immigrant psyche is an ambitious endeavour that would smack of hubris if it weren’t for its touching sincerity. An insiders’ guide to the British desi experience from the 1600s onward, the book examines all that’s borne aloft by the “whirling wind of migration” — from the eminently edible, such as the invention of cheap ‘Balti’ cuisine, to the downright hard-to-swallow — bombers and biradari, the regressive system that considers ‘honour killings’ as an apt retribution for the ‘shame’ that sullied chastity — or merely, a woman’s exercise of agency.

His journey begins in Birmingham, the Mecca of curry munchers, where he takes a deep, demystifying whiff of the curry cult. Through anecdotes about various curry house owners, he traces back the curry’s etymology and (apocryphal) legend, and describes, down to the last, lipsmacking detail, the finer distinguishing points of Balti mutton curry. In the light of the 7/07 attacks on London’s transport systems and the fortituously bungling Glasgow bombers, Sardar travels from Leicester to Bradford and Glasgow to examine the rise of radical Islam; the “disease that is in us, is of us, and within us”. He also travels back in time to his own Hackney childhood, and the lasting impression that violent racial discrimination left on him, in the shape of a misshapen nose.

Sardar’s method of combining autobiography and anecdotes has a vivid, engaging effect when he counterpoints the British view of colonial history with what was related to him by his ‘hakim’ grandfather. Through Urdu couplets, his Nana had spoken of the Battle of Plassey and Jallianwala Bagh as instances of firangi betrayals and brutality. Which is why he mutinously burned his textbooks in a ‘pyre’ on his desk, upon hearing his history teacher Mr Brilliant’s version of history, in which the 1857 ‘struggle for freedom’ was a ‘mutiny’ and Tipu Sultan was denounced for his ‘savage behaviour’.

On other occasions, however, his rambling anecdotes seem irrelevant. One does ponder the worth of knowing all the names tried for his first-born daughter, or that his wife flung a bucket of water on him right before their (arranged) marriage. This is one loaded Balti, but it may get a little wearying to chew all the way through.