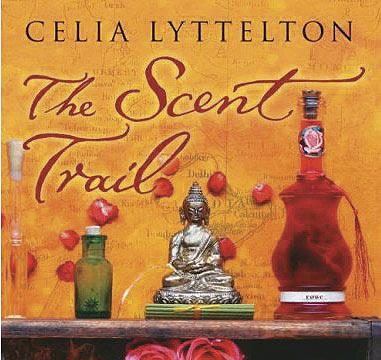

As a lifestyle journalist Celia Lyttelton wrote for pioneering glamour rags such as Vogue, Harper’s, Vanity Fair and Tatler. Then she set her heart on that ultimate couture accessory — a scent of her own. Soon she followed where her nose led — from the perfumer’s fairground of Grasse for a whiff of mimosa, through fields of Turkish damask rose, in search of petitgrain and neroli at Moroccan souks, into the earth of Italy after the iris root, to India guided by heady zambac jasmine and calming vetiver. Arriving at an intimate understanding of each of ‘her’ aromas, she put a stopper in the bottle — and let out choice verbal whiffs from The Scent Trail for the curious sensualist.

Is it egotistic to want such an exclusive, one-of-a-kind odour? If it is, it’s at least a more emancipated ego than the one relying on labels!

In the last few years or so, trendsetters have been turning away from designer house fragrances. Together with the movement towards simples and single notes since the late 1990s, this has completed the conversion of even mass-market buyers to confidently mixing personalised ‘signature scents’. (Hence the success of The Body Shop’s and Jo Malone’s blend-your-own bottles.) Bespoke perfume is the pinnacle of this cult of individualism.

Yes, that custom-blended perfume, never to be worn by another person, comes at a hefty price. Not many outside the peerage (the author is one of the pedigreed) or celebrity A-lists can hope to get their mitts on one. Back to ego strokes, then?

Well, given the way scents tug on the umbilical cord of memory, perhaps we should be speaking of Id instead. Lyttelton’s bespoke perfume, for instance, reflects — and recreates — scent memories (à la Proust) of childhood at her grandparents’ home by the sea and her youthful introductions to the ‘exotic East’ on journeys with her mother.

Then again, in a Baudelairian series of correspondences, Lyttelton’s pursuit of her personal perfume involves a colour profiling, an experience startlingly like a session in the fortuneteller’s tent.

Lyttelton’s tone vacillates between knowledgeable reportage and self-conscious journalising. If it sometimes makes you blink in surprise, it doesn’t unduly jar while demystifying the alchemical-musical vocabulary of perfumer’s organ, alembics and stills. The narrative’s somewhat self-absorbed tendency to constantly reiterate the point of this ‘olfactory odyssey’ — ‘a scent for Celia’ — is counterpointed nicely by more objective information nuggets every few pages. These short boxes (on, say, the anatomy of ambergris or essence in Ayurveda) make for a book that can be read two ways — as a chronological narrative or as a fount of fragrance wisdom to dip into at leisure. It helps that she doesn’t overtly ‘educate’, but rather shares the reader’s delight at discovering an attar of tomato leaves or that musk smells of ‘concentrated fart’.

Well worth inhaling.