I like travelling in Kerala, with its air of timelessness and fecundity. Even though I am from neighbouring Tamil Nadu, Kerala has a foreignness that makes every moment fresh. So, I quite looked forward to a book on the ‘new emerging Kerala’, but what I get is a mixed bag. Inside are some lovely pieces, and then some that prove nobody believes in editing anymore. Editor Shinie Antony’s gushy Foreword is my first warning of things to come (“the path to soul-neutering”? And how does one “criss-cross into the global spotlight”?). Inside, she spoils what could have been a crisp collection with vague rambling.

Antony is at her best when she transforms interviews in Malayalam into taut monologues — the two here are among the best in the book. The memoir of 90-year-old Gowri Amma, a veteran of the Communist Movement, is just a tiny slice of her life but one that captures perfectly the mood of those times. And the last, ‘Happy’, as told by Omana, a Malayali housemaid in Mumbai, is so perfect it could be framed.

Susan Visvanathan’s languid tale of an interrupted train journey keeps perfect step with Kerala. It’s the kind of meandering piece I love to read on a slow train to nowhere. In ‘Countryside’, the old-fashioned theme of a village girl deserted by her ‘foreigner’ husband is slowly and charmingly told by Mukundan. Sadly, Dalrymple is not at his best; in ‘Sisters of Mannarkad’, a story of how a legend brings Christians and Hindus together, he is clearly floundering and disengaged with South India.

K. Satchitanandan’s essay (‘Everyday and the Avant-Garde’) is best described in Anita Nair’s eloquent words — “inviolate, insoluble, and heavy with incomprehensibility”. Honestly, what is such a leaden academic paper doing here? Nair herself is accomplished as she demolishes literary critics in her humorous story ‘Orhan Pamuk, Nair and I’, and makes one wonder if she could be the eponymous author?

Of the translations from the original Malayalam, some like Paul Zacharia’s tight satire ‘Hijack’ lose nothing in translation, and the pathos of the Malayali IAS officer wanting to hijack a plane home is brilliantly built up. But ‘The Clove’ as translated by Sangeetha Sreenivasan is a serious disservice to author Sarah Joseph. The sensuality, which one imagines heavily imbues the original, is entirely lost and the language is rank bad.

Artist Yusuf Arakkal, whose paintings I hugely admire, disappoints in his prose — it’s dry and boring. Actually, it becomes a bit tedious when most of the essayists indulge in breast-beating about all the famous Malayali flaws — lazy labour, activism, endless arguments and so on. What essays should be like is illustrated by Hormis Tharakan, whose ‘Sitrep Seventies’ is by far my favourite. The descriptions of his Parayil family ancestors, the anecdotes about their church connections, the Naxalite struggles and his own role in the police force — his account is gripping and a perfect example of history made into story, something no Indian author has done well so far. Tharakan should write more; I would love to read his autobiography. Equally brilliant is Suresh Menon with ‘No Sex Please…’ Full of sly humour, it’s a nostalgic and loving look at Irinjalakuda, Menon’s birthplace.

Another one I loved was ‘Fort Lines’, a brief, taut play by Shreekumar Varma about a reformed activist. Moving sharply from scenes of how Jayesh staged rasta-rokos with thugs to the present Jayesh studying for the Civil Services, it is stark and moving and made me want to see it put on stage.

S.S. Lal, Jayant Kodnani and Sheila Kumar are good and experienced, taking you easily along their practised ways. The hurdles are essays like ‘Chinese Takeaway’, ‘Music and Lyrics’ or ‘A for Anglo’, which are irritatingly and obviously commissioned to cover predictable areas. Where’s the whimsy? Why break the magic created by little gems like ‘The Gift’ by 13-year-old Nimz Dean or Vinod Joseph’s ‘A Matter of Faith?’ They are the ones that make the book worth reading.

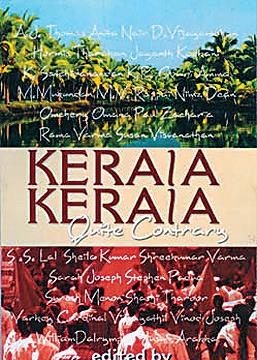

Eclectic writing from Kerala

A collection of thoughtful, satirical, passionate even whimsical pieces introducing readers to the 'new emerging Kerala'

Eclectic writing from Kerala

Eclectic writing from Kerala