Even before the term ‘popular culture’ gained currency, the Epics had captured the imagination of artists and artistes alike. Virtually all forms of wall paintings and sculpture traditions across the country—be it the pattachitra, madhubani, kohbar painting, patua paintings or the mandna tradition terracotta sculptures—all look towards the Epics for their thematic sustenance. The Epics must be viewed against the backdrop of not only the value system and ideals they represent but also visual and performing art traditions.

In this backdrop comes the latest lavishly illustrated tome of Ramayana by J.P. Losty and Sumedha V. Ojha with paintings from the Mewar Ramayana prepared for Rana Jagat Singh of Mewar (1628-53) in the miniature tradition. It is the first time that these paintings from different locations have been collected and presented in a single volume. Largely sourced from the British Library in London, the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sanghralaya in Mumbai, the Rajasthan Oriental Research Institute and a few private collections, the volume of nearly 400 paintings from the Mewar school of miniature paintings is in amazingly good condition. It’s no surprise that J.P. Losty was the former curator of the extensive Indian visual collections in the British Library and is one of the world’s leading authorities on paintings of colonial India. Sumedha V. Ojha is a writer and speaker on ancient India with a special focus on a gendered analysis of ancient India.

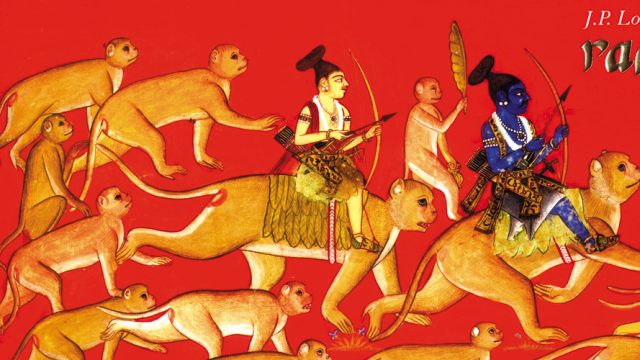

Painted by mid-17th century artists, the saga of Ram has been artistically turned into an elegant expression of Rajput ideals and society. The main painter during Jagat Singh’s reign was Sahib Din and the entire lot seems to have been painted by him and possibly by other ateliers under his supervision for there is an invisible thread that binds the works together. Interestingly, the stylisation is so brilliant that it lays the ground rules for the way all Mewari artists drew the human figure in subsequent centuries. The spatial and temporal differentiation is superb as elements are separated by landscape to delineate depth. The colours take a leaf out of the royal lifestyle of the Rajputs, replete with grand palaces and bejewelled queens and kings.

The book is divided like the Ramayana itself—into kands or chapters. Each painting has an explanation and a tale behind it. Since the entire set of paintings follows a chronological pattern, there is a connect in the visuals as the characters move around the designated framework yet the painter takes the occasional visual liberty, akin to a poetic license. While Sahib Din glorifies deeds of heroism, he paints Ravan, almost sympathetically, as the flawed and tragic hero. In some works, there is a graphic delineation of the narrative, for instance when Kumbhakaran is killed, the way his arms, head and body fall is depicted as if it were a film strip.

Most of us have grown up listening to stories from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. But the way the book has handled them, it reaches out to Indians and Indophiles who might be interested in a step-by-step telling of the epic in the most arresting manner.