This is a food book with a difference. Instead of talking about the different kinds of Indian cuisines, Colleen Taylor Sen sets out to document Indian food through history, something which no one has done before. She traces Indian food through the Vedas, pointing out that alcohol was frowned upon, though other intoxicants like som ras were used for religious rites. Since then soma has vanished from Indian botany and remains an unidentified ingredient. The book is peppered with similar interesting titbits focussing mainly on spices which Sen sees as the connecting thread between the vast variety of Indian food.

There are also 14th-century recipes and even an Ode to Ghee. We learn about the various cookbooks starting with the seminal work attributed to the mythical ruler Nala in whose honour all northern Indian cooks were called maharaj. Chandragupta Maurya was apparently a Jain and starved himself to death in the ultimate Jain fast. Many of the Muslim rulers ordered cookbooks so that their five senses could be stimulated by the different aspects of Indian food.

Painstakingly following the history through empires and religions, Sen gives us a complete picture of the influences on modern Indian cuisine. She also traces the different strands from Avadh to Hyderabad and Kashmir—documenting the fabled Kashmiri wazwan served on celebratory occasions and the various conceits created by the royal cooks of Avadh and Hyderabad who excelled in making pulao look like pomegranate seeds or could cook a different daal dish for every day of the year, as Shah Jehan’s jail chef claimed.

There are lists of incredible ingredients or the different poetic names given to pulao—biryani somehow failed to inspire such poetic heights. Curry apparently came from a Tamil word and the Portuguese in the century they ruled Goa changed Goan cuisine totally while apparently influencing the Bengali tradition of curdled milk sweets.

Much of the work was translated from Sanskrit with the help of researchers and it is obvious that Sen herself is not too familiar with Indian languages. To a Bengali, the glaring error would be classifying bhetki as a sea fish, which she does when she talks about Bengal’s food habits on the eastern and western sides. Odiyas might be annoyed at having Lord Jagannath’s splendid kitchens left out, though Sen does talk about prasad and its religious significance. According to her, Assamese cuisine is truest to the vedic traditions, showcasing different flavours, sour, salty, sweet, astringent in every meal. Though she does talk about the chilli being introduced from North America, she does not delve into how it spread in its different incarnations across India. However, given the vast amount of research that has gone into the book—coming a good 25 years after K.T. Achaya’s groundbreaking Indian Food: A Historical Companion—Sen is wise not to attempt an overload.

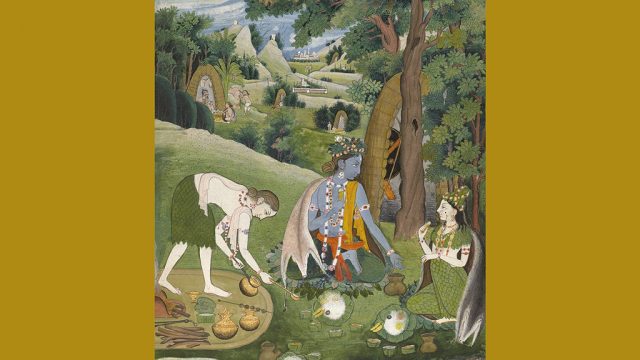

While the book’s reach stretches out to the 21st century, embracing the global spread of the Indian diaspora and modern Indian eating habits which have resulted in the growth of diabetes, it must be admitted that Feasts and Fasts’ true wealth lies in the historic sections with the pictures, the poems and the recipes—though many of them are untested and most follow the habit of not giving exact measures, relying upon the chef’s skill.