The book under review positively reels under the evocative weight of its subtitle. “What I know are fragments,” Shepard writes in her prologue, “I am here to weave them together, to create a new story, a story uniquely my own.”

Sadia Shepard is someone whose rich and complex inner life is clearly a source of endless fascination — at least to Sadia Shepard. She is absolutely enamoured of her mixed blood. Everything around her seems to be hell-bent on reflecting back to herself her own story. Sitting at the Film Institute in Pune, a friend, Rekhev, describes what used to happen here, in the following, choice, words: “‘Place memory,’ he says. ‘The imprint of past action on an environment. We are surrounded by ghosts here.’”

In a library, she chances upon a book about Amrita Sher-Gil, and it, too, becomes a mirror: “I look at her picture, tracing her Hungarian parent in her face, then her Indian one. A half-half person. Like me.” A simple instruction from her mother — “Come home” — becomes a heartfelt plea to fulfil an impossible destiny, an opportunity to dwell on the inherent complexity of the term.

The book is the story of the fulfilling of a promise, made to her grandmother as she lay dying (and helpfully reiterated even after she is dead, in a series of dreams): “Go to India, study your ancestors.” Her grandmother, Nana, is a touchstone for young Sadia, a spinner of tales, a secret-keeper, a repository of timeless wisdom in whose dual identity (she was a Bene Israeli Jew who changed her name, and religion, to marry a Muslim man) the author finds yet another echo of herself.

She writes episodes in her Nana’s life in the present continuous — a sneaky trick to make you think that this is actually what her grandmother thought, this is actually what happens. I don’t buy it: not for a minute. “Nana looks up at him, her eyes filling with tears. She loves him too much for her own good, she thinks.” I mean, really. Really?

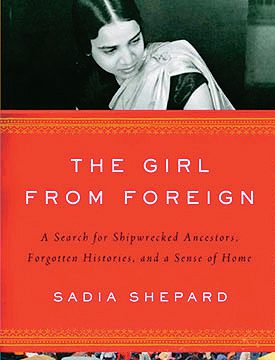

The Girl from Foreign traces a particularly American journey: a journey to ‘find oneself’, to come to terms with stuff in one’s past, to achieve ‘closure’. It’s possibly a valid course of psychotherapy, but it doesn’t make for a terribly good book.

Unlike, for example, Mrinal Hajratwala’s Leaving India, the reader is left feeling like she knows rather too much about the author and precious little about anything else.