All quests make compelling reading and this book has not one, but two. Aatish Taseer embarks on a journey to discover the Muslim part of identity, but that identity is, itself, part of a more fundamental search — he wants to get to know his father, the prominent Pakistani politician, Salmaan Taseer, who had parted ways with his mother almost as soon as Aatish was born. As he grew up, Salmaan Taseer remained an unknown quality, who fended off — while not absolutely rejecting — his son’s few and tentative attempts to make contact. Aatish was brought up by his Sikh mother in India, but as an adult, well adjusted and doing well, he nonetheless felt the need to excavate his complicated Muslim-Sikh-Indian-Pakistani heritage, so inextricably entwined with the savage history of the subcontinent. At the core of this tangle was, he felt, his father.

His journey to his father’s bungalow in Lahore took him through Mecca, Istanbul, Damascus and Tehran and, in Pakistan, through Hyderabad (Deccan) and Karachi. His descriptions of places and encounters are crisp and illuminating, but what really holds the narrative together is the fact that this is unequivocally a personal journey, a pilgrimage of sorts; it is not a travelogue. It is also a vivid evocation of being Indian in Pakistan — the familiarity and yet the unfamiliarity, as he describes it.

Interacting with theology students in Damascus, Marxists in Turkey, pilgrims in Mecca and feudals in Sind, Taseer explores how they see their ‘Muslim-ness’. For instance, a Turkish acquaintance who says that there is a ‘civilization of faith’ which binds all Muslims together, or his father’s claims to being a ‘cultural Muslim’ — a category which does not practise but feels one with all the cultural aspects of Islam — or those who feel Aatish should not wear the kara his Sikh grandmother gave him because he is Muslim by virtue of having a Muslim father. It is the view of a secular observer, imbued with a post-Enlightenment liberal spirit, who finds the ways of exclusivist faith both alien and disturbing. Though the book’s subtitle, ‘A Son’s Journey through Islamic Lands’, signals that such explorations were to understand the unknown side of his heritage, it is hard not to read this as extending his personal quest into the wider question of Muslim identity, and that works less well. In the end, Taseer convincingly describes the way he has come to terms with his missing father; he has laid that particular ghost by finding it wanting, both intellectually and emotionally. He can move on. Stranger to History is a moving and beautifully written account not just of Taseer’s uniquely individual issues with parentage and cultural affiliation, but also an exploration of what makes us who we are and how we decide what we don’t want to be.

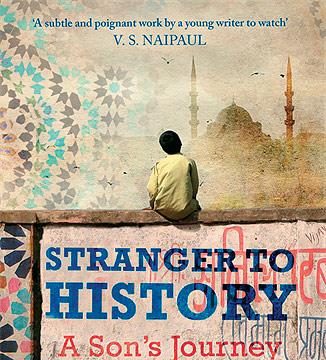

In search of identity

Author Aatish Taseer explores his individual and cultural identity

In search of identity

In search of identity