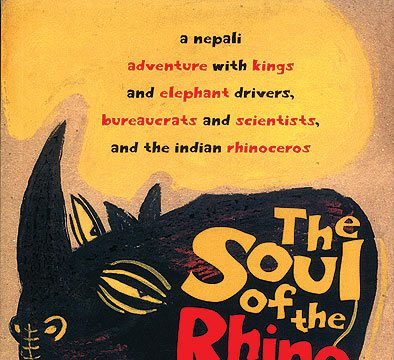

It’s difficult not to be fascinated by a creature as conflicted as the rhino — pugnacious yet placid, incongruous to the eye yet incredibly agile and, as Hemanta Mishra declares in the first few pages, “ugly yet enchanting”.

This paradox is also the focus of mythological creation accounts of the rhino. In one endearing story mentioned in The Soul of the Rhino, it is described as a “masterpiece of the art of imperfection” — with the skin of an elephant, the hooves of a horse, the ears of a hare and the heart of a lion.

This book chronicles one man’s lifelong enchantment with this strange beast. Mishra joined Nepal’s Ministry of Forests in 1967, having completed a course in forestry. His first assignment was to explore Chitwan — the sprawling terai wilderness.

Very quickly Mishra realised he was woefully under-prepared for real forests. Tapsi Subba, an elephant driver, came to his rescue. Tapsi was from the indigenous Tharu community. He was foul-mouthed, impatient with city-boys like Mishra, but knew the forests and its largest and most famous occupant, the rhinoceros, in the most delightful detail. With him Mishra saw the shocking aggressiveness of two rhinos thrashing towards an orgasm, learnt that rhinos often urinate while walking backwards, spraying urine more than two metres away, and that their communal defecation sites serve as a means of communication and territorial demarcation.

He also learnt the ‘shamanistic’ local customs of the Tharus (rather bloody affairs involving goat and pigeon sacrifices) which he would have to respect and follow if he was to have their co-operation.

In the 1970s Nepal’s conservation movement was in its infancy. So, while Mishra and his companions were free to experiment with paradigms, they had to balance scientific conservation practices with local needs and wisdom, and the imperatives of conservation with those of government and bureaucracy.

The balance was tested on occasion, leading to grave self-doubt. At one time, King Birendra decided to perform the Tarpan, a ceremony that involved killing an adult male rhino to offer its blood to the souls of ancestors. There’s a haunting description of the latter — of the king stepping into and emerging bloodied from the eviscerated skin of the dead rhino strung up between trees.

There were major successes too — like the relocation of rhinos to establish a second viable breeding population in the Royal Bardia National Park in southwestern Nepal and the creation of community tourism initiatives in Chitwan.

This is the eloquent and touching story of Nepal, rhinos and a personal quest. Part memoir, part eulogy (to the rhino) and natural history — so delicately interwoven that it’s difficult to separate the man from his rhinos.