India has a long history of nature writing, going back to some of the earliest literature, including the Rig Veda, which contains several hymns to nature. One of these is addressed to Aranyani, goddess of the forest: “Aranyani. Aranyani. Timorous spirit of the forest, elusive goddess who vanishes amidst the leaves…At twilight your presence fills the forest…Mother of wild creatures, your untilled forests are full of food, fragrant incense and sweet herbs — Aranyani, accept my prayers, sheltering goddess of the trees.”

Ancient poets and philosophers drew inspiration from India’s rich and diverse ecology, her forested plains, rivers and mountains, as well as the sea. Both the Mahabharata and the Ramayana epics contain episodes set in the jungles of the subcontinent, a primal wilderness that is both discomfiting yet protective of those who enter its green embrace. The Sanskrit poet Kalidasa composed narrative verse and drama that celebrates nature. His Meghadutam contains one of the most remarkable metaphors — a cloud shaped like an elephant that drifts over the verdant countryside. Observed from this flying jumbo the landscape below is described with lyrical precision, curiously similar to satellite images we find today on Google Earth.

The earliest invaders and travellers to India were struck by the lush fertility of the land. The Greek historian Megas-thenes who followed in the footsteps of Alexander, could barely contain his sense of wonder for the natural resources he discovered: “India has many huge mountains which abound in fruit-trees of every kind, and many vast plains of great fertility intersected by a multitude of rivers…It teems at the same time with animals of all sorts — beasts of the field and fowls of the air — of all different degrees of strength and size. It is prolific, besides, in elephants, which are of monstrous bulk, as its soil supplies food in unsparing profusion…”

Many centuries later, Mughal writers, too, were struck by the complex array of species that they encountered after crossing the Hindu Kush. The Baburnama and Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, both imperial memoirs, describe the birds and other creatures observed in India, colourful elements of the land they conquered. Court painters were commissioned to copy miniature images of these species with scientific accuracy. Scribes who recorded the emperor’s memoirs included both physical descriptions as well as accounts of the bird’s or animal’s behaviour.

Of all the visitors, interlopers and invaders to enter India, the British were the most enthusiastic naturalists. Botanists like J.D. Hooker made extended expeditions into the Himalaya, cataloguing and classifying thousands of different varieties of flowers, shrubs and trees. Animal life, particularly those species identified as ‘game’, was of particular interest to colonial hunters who expressed curiosity and admirations for their prey, even as they decimated the population. The hunter-naturalist became an iconic figure during the Raj, entering the jungle with a rifle in one hand and a pen in the other. G.P. Sanderson’s Thirteen Years Among the Wild Beasts of India is a classic example of the genre, which combines zoological research with bloodsport. Under the British rule, man-eater stories became a popular subject in India, a junglee variation on detective novels, in which the hunter pursued an elusive killer through the forest, picking up clues along the way — identifying pug marks, blood stains and alarm calls.

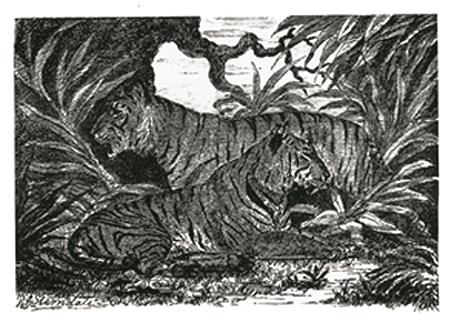

Jim Corbett is the best known of these hunter-naturalists. Born in India, he had a closer connection with the land than most of his British compatriots. He approached nature with a sympathetic and observant eye, even as he tracked down man-eating tigers and leopards, one predator pitted against the other. Corbett was among the first to voice concern about dwindling populations of wildlife, particularly tigers. In a sentence that has been quoted more often than any other statement on Indian wildlife, Corbett writes: “The tiger is a large hearted gentleman with boundless courage and when he is exterminated — as exterminated he will be unless public opinion rallies to his support—India will be poorer by having lost the finest of her fauna.” Unlike many of his contemporaries, Corbett was acutely aware of the fragility of nature and its vulnerability to human encroachment.

Extracted from the introduction to Writing Outdoors: A Natural Reader, edited by Stephen Alter and published by WWF-India and the Hanifl Centre for Outdoor and Environmental Study at Woodstock School.