Less than a hundred years ago, the pilgrim trail was a far more dangerous place than it is today. Cold weather and landslides took their toll, as did some of the local fauna — several of the victims of the man-eating leopard of Rudraprayag were devout Hindus on their way to the holy shrines in the Himalaya. Big cats, with or without a taste for devotees, are now scarce or nearly extinct, while good roads, cushy SUVs and even helicopters make for a considerably easier passage for pilgrims. For the most part, that is; a few journeys remain a challenge even for hardy travellers.

The trail to Mount Kailash and Lake Mansarovar in Tibet is one of them. The 200km trek winds upwards from northern India, along the Kali river, into the mountains and high plateaus of Tibet. The lake is over 4,500m above sea level; the circumambulation of the 6,638m peak takes pilgrims through the 5,500m-high pass at Dolma. Conditions here are brutal. Even very fit and experienced climbers treat such altitudes with a fair degree of caution.

The pilgrims, though, are mostly sedentary urban dwellers with little outdoor experience. Most are at least middle-aged, some elderly. A profound faith keeps them going. For the Bon (an ancient Tibetan faith), Buddhists, Hindus and Jains alike, Mount Kailash and Lake Mansarovar are imbued with the deepest possible spiritual significance. For thousands of years, Indian pilgrims have been making this arduous trek. Twentieth-century politics closed the route for years until an agreement between the Chinese and Indian governments opened it again for escorted groups.

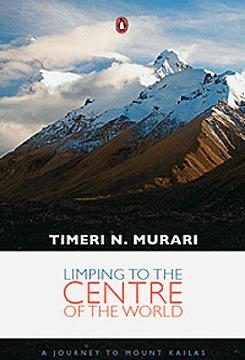

Author (his oeuvre spans journalism, novels, plays and scripts) Timeri Murari travelled with one such group in 2005. His account of the journey to this very remote part of the world is absorbing, intriguing and honest. Skills honed as a historical novelist (though currently Chennai-based, Murari worked in the West for decades and is arguably still better known outside India) mean that the narrative rarely slackens and is always informative; though perhaps not quite enough for experienced outdoors types, who may chafe at what is after all the particular perspective of an urbane, educated city-dweller. The pleasure in the book lies elsewhere; Murari’s view is consistently honest — he calls it as he sees it. This is true whether he is writing about Gujaratis, the Chinese, or even about his companions. Pilgrimages are something like an extreme form of package tour. Regular travellers unused to the genre can find their companions’ objectives and behaviour quite alien to their own. Yet Murari never lets a judgement skew what he has to say about his companions’ charm and warts. He compares neither their piety nor their pettiness with anything, not even his own views. But he depicts them nonetheless, and this, even more than the holy pilgrimage, is what makes the book come alive.