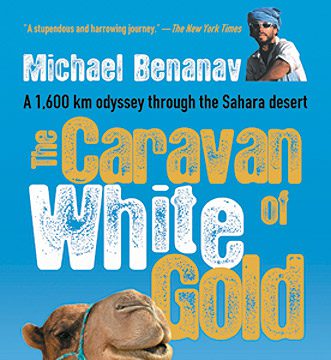

In case you’ve ever wanted to run out and do a bit of salt mining under the blistering Saharan sun, this is definitely the book for you! But American desert-fancier Michael Benanav quickly reveals that he’s not your average tourist: “I had been a wilderness guide in the western United States for about ten years and had spent weeks at a time roaming its deserts by foot. Without a pack animal, I had carried all my supplies, even gallons of water, on my back, and had become expert at ignoring pain while hiking for many miles with shredded feet. The thought of not showering or changing my clothes for the estimated 40-day camel journey struck me as, at worst, a minor inconvenience and, at best, a chance to set some new personal benchmarks for sustained filth.”

His journey begins — as so many modern journeys do — on the internet. A Timbuktu-based tour-operator prices the approximately six-week, 1,000-mile round trip at $5,000. That’s almost double what the 33-year-old is willing to pay. The operator, whose name is Alkoye Touré, quickly convinces him that prices can be made to suit the pocket and Benanav sets out for the West African country of Mali.

Of course things go awry! For instance, in the taxi to Timbuktu, when he meets a tour operator called Alkoye Touré, Benanav assumes it must be the same man. Except it isn’t. When the original operator finds out, he’s spoiling for a fight. But Benanav is the kind of seasoned traveller who knows (a) he will be scammed, (b) he can choose to get over it and move on. His writing style is workmanly rather than poetic but that’s what makes it exactly right for the austerities of the desert. Only an extremely naïve Westerner with terminal wanderlust would sail off on an elderly camel in the company of an illiterate, Arabic-speaking man with no inclination to be a guide-cum-nursemaid. But only an extremely resilient, philosophically mature person would survive such a trip and return from it giving thanks to Allah. Which is what Benanav, though Jewish, fervently does.

The journey begins with a sinus infection, but Benanav must either head out right away or drop out forever. Walid, the guide and camel driver, will set off to pick up his cargo of salt regardless of the foreigner. In order to earn a living from this gruelling trade, he must make the most of the limited time he has. Meanwhile Benanav has no radio, satellite phone or buddies waiting to bail him out with first-aid kits and helicopters. Taking his cue from the intrepid explorer of the Arabian Peninsula, Sir Wilfred Thesiger, he tells us, “Part of true adventure — and the way explorers travelled by necessity until recent times — is pushing beyond the reach of outside aid, managing situations with the resources one has, being smart while praying for a touch of divine grace. You perceive your environment and yourself differently if help is merely a phone call away.”

In spite of the expression ‘back to the salt mines!’ the salt I am familiar with is a product of the sea, not a mineral that requires mining. So it was enlightening to read that for connoisseurs, such as Malians, the different grades and flavours of salt are prized in exactly the same way as a fine wine. Unlike wine, of course, the deposit is buried deep underground in vast flat layers and will one day run out. But the trade is centuries old and for the time being, at least, it seems set to last.

For Benanav, the goal of the journey is to travel with a caravan, meaning a contingent of 70 or more camels and their drivers, all moving and resting at the same time. I will admit I found his insistence quite annoying because it seemed entirely contrary to the whole Zen and the Art of Picking Up Camel Dung aspect of such trips. Fortunately there’s just enough Zen to counterbalance the author’s Inner Brat. The immensity of the Sahara and the poignant sturdiness of those who eke a living from it transform him and heal him. When he eats his first good curry after weeks of subsistence food, he says, “It was so good, so beautiful, tears gathered in the corners of my eyes.”