Characters often travel, or wander, in comic book narratives, because wandering allows for a rapid change of scene, and makes it possible to extract characters from a given situation with an economy of panels: the wanderer can always run away. Having said that, while there are many wandering characters (in Garth Ennis’s Preacher, for example, or Watsuki’s Rurouni Kenshin), there aren’t that many comics that concentrate on travel for itself. I’m not referring here to the quest, mind you. Quests are common in comics and indeed in most fantasy, but they aren’t quite the same as a journey, since they are oriented towards reaching a goal. Of course, these are tricky terms to throw about, and a good quest usually involves an engrossing journey. But the story isn’t about the journey.

Not so Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, one of the most beautiful and subtle comics ever produced. It is done on an extra-large page format in subtle tones of sepia and grey, and has no words. The story is told only through pictures, without speech bubbles or captions. Yet the story lacks neither accessibility nor clarity. It is about a young father who leaves his wife and child to travel to a foreign land, where he cannot speak the language or read the script, to find work and make a new life for himself and his family, who eventually join him. Both his home world and the new one are profoundly yet serenely different from ‘reality’. Some of the visual vocabulary, like the menacing dragon of the young man’s home world, does suggest where the roots of this tale lie: in the story of Shaun Tan’s ancestors who left China to settle in Australia, but because the tale pulls us into a bizarre fantasy universe, we are not distracted by the earthly history that must nourish it. Instead we read it as a pure journey: moving from the familiar to the scarily unfamiliar, which through the kindness of strangers who become friends, once again becomes the comfortingly known.

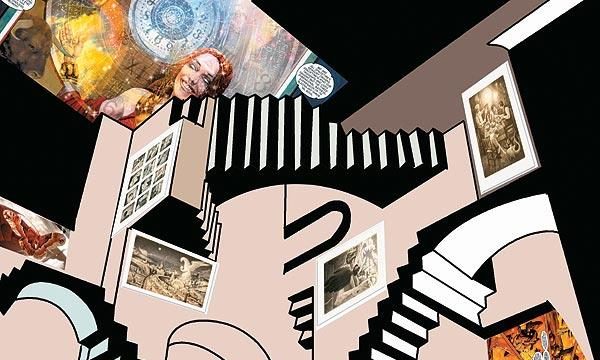

A different kind of journey is the set piece ‘trip’ that occurs in the middle of Alan Moore’s Promethea series. Promethea is arguably Alan Moore’s masterpiece, a tour de force into which he puts everything he knows about the Kabbala and the esoteric knowledge. The story arc follows Sophie Bangs, a New Yorker in a near future world of flying taxicabs and ‘science heroes’, who becomes Promethea, a goddess born in ancient Alexandria, protector of art, science, learning and the imagination. As Sophie learns how to be Promethea, she journeys into what Moore calls the ‘Immateria’, the place where all ideas, concepts and the roots of magic live. While trying to rescue and help Barbara, the woman who was Promethea before her, she and Barbara find themselves journeying along ‘Route 32’, the central route up the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. Each of the Sephiroth, or levels, of the Tree forms a stop on their trip, with its own Hebrew letter, magical symbol, fragrance and significance: each is a pocket realm.

This journey is a coming of age rite. Whether you call it pabbajja or Inter-railing, travel is essential for young people to be able to come home. On the way they are changed. Thus, the journey of the Buddha in Osamu Tezuka’s eight-part series of that name is the third great travel tale I’m including here. Like Sophie, the Buddha is travelling towards himself, but in this case we already have a template for his journey: we know where he went and why. However, Tezuka takes pardonable liberties with the Buddha’s story: he introduces fictional characters, makes up incidents and changes others. Tezuka’s spare, clean line art, the childlike hands and feet of all his characters, the tiny snub noses and the large eyes, humanise even the ‘evil’ characters. With an economy of meaning that touches genius, Tezuka’s lines make spaces for the characters to traverse: the sal grove, the Deer Park, the palaces of Vesali. So the journey is not about progressing, or learning, or growing old and powerful: it is about returning. That return is redemption.