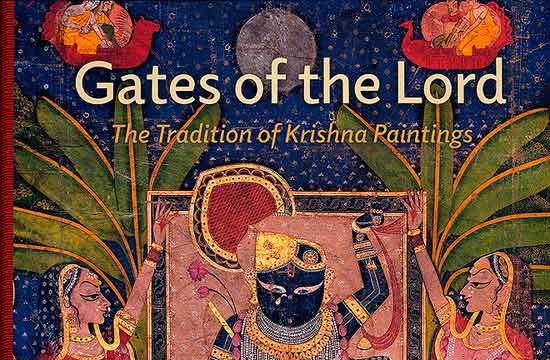

Published in conjunction with the ongoing exhibition by the same name at the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago (through January 3, 2016), this lovely book is a tribute to the intimate and exquisite visual culture of Pushtimarg, the Hindu denomination of western India that’s dedicated to the worship of the seven-year-old child-god Krishna as Shrinathji at Nathdwara (literally, ‘gates of the lord’). A deep, centuries-old intertwining of devotion and art comes vividly alive in the nearly 200 images that work their magic in this book, and I am disinclined to refer to it as coffee table publishing despite its muted richness because it’s matched by the academic gravitas that Mapin brings to its titles. Both the exhibition and book meticulously document pichvais (the Nathdwara style of painting on cloth) as well as textile hangings, embroidered and brocaded pieces, illustrated manuscripts, and icon images commissioned by pilgrims to the temple town. Today, visitors would have to search for true examples of pichvais in the back-alley homes of Nathdwara’s dwindling numbers of master practitioners.

The opening essay is written as a personal journey by the book’s editor Madhuvanti Ghose, Alsdorf Associate Curator at the Art Institute. If she weaves her childhood memories of visits to Nathdwara with her artist mother into the context and evolution of Pushtimarg’s aesthetic heritage, the encyclopaedic Amit Ambalal, works from whose rare collection of pichvais have been loaned to the exhibition, delves into their history/mythology (with their intriguing overlaps). Rounding up the sumptuous study are Anita Shah’s “story of a Pushtimarg family”, Tyrna Lyons’ introduction to the varied careers of three later Nathdwara artists, and Kalyan Krishna’s exposition on narrative textiles. Everything from haveli sangit (mystically insightful poetry set to music and performed at each of the eight daily darshans at Nathdwara) to the spiritual foundations of seva (loving service to the deity) gets its due. I also appreciated practical considerations such as a labelled sketch of the inner sanctum of Shrinathji (for cross-referencing) and detailed write-ups accompanying each of the catalogued illustrations, which always enhance my enjoyment of art. Having read the book, now I really must go to Nathdwara!