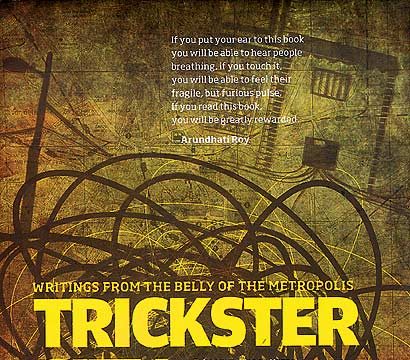

When you’re done rolling your eyes at her hyperbolic cover blurb and read this volume, you’ll find that Arundhati Roy is actually on to something. “If you read this book, you will be greatly rewarded,” she assures us. I did, and was, and if your interests encompass Delhi or indeed any city and the way its inhabitants negotiate an often adversarial urban experience, then this book is essential reading.

The stories — by young working class writers associated with the Cybermohalla initiative of the Ankur Society for Educational Alternatives and the Sarai programme of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (both of Delhi) — map a city most readers won’t recognise. Dakshinpuri, a ‘resettlement’ colony that resulted from an earlier spate of demolitions during the emergency, lies to the south. Nangla Maanchi, a squatter’s colony whose demolition in 2006 is both spark and engine to this book, lies on the bank of the Yamuna, historically the eastern edge of the city. The still rural village of Ghevra, far away to the northwest, is where the oustees of this particular demolition have been ‘resettled’ by the government, hours and a life away from the world they know. The shadow of the Commonwealth Games, dark inspiration for the uprooting of the residents of Nangla Maanchi, hangs over everything.

But this volume is much more than an impressionistic litany of wrongs. Arish Qureshi gives us a finely rendered day in the Idgah abattoir in ‘The Slaughterhouse’, while Yashoda Singh teases out a Muslim housewife’s sense of injustice at being hostage both to her landlords and the local police in ‘The Tenants’. Daily life isn’t the only canvas, either. Thus Rakesh Khairalia, in ‘Daily Acceptances’, writes: “Writing has a likeness with wandering. A vagrant thought gathers wisdom from the many contexts it travels through. It braids within itself the shivers and the sediments of different experiences, and the texture of their differing tempos.” When you freight craft and authorial intuition with experience, the result can be magical, and there are many moments like this to savour in Trickster City.

Most of the pieces in this book were originally published in Hindi in Bahurupiya Shehr (Rajkamal Prakashan, 2007), while a few were added in later. They’ve all been translated, sympathetically and with verve, by Shveta Sarda.

And everywhere, contrary to what you might have been led to expect, is the distinct flavour of hope: of a new life, a new home, the belief that the city still has space to grow. Ghevra won’t always be an outpost. Daskhinpuri too was once the edge of the world. Today, you’ll know it as lying close to Sainik Farm, the malls of Saket a walk away.