Somewhere between the Black Sea and the Caspian, Europe segues into Asia. Fertile and rich in trade routes, this region is the cradle of many cultures and, inevitably, of much conflict. Since Troy, 3,000 years ago, Greeks, Persians, Romans, Armenians, Georgians, Turks, Swedes, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Romanians, Poles, the English, the French and assorted tribes have scrapped back and forth across the rolling steppes and the Caucasian mountains. The most vicious World War II battles took place here. In 2008, Russia invaded Georgia.

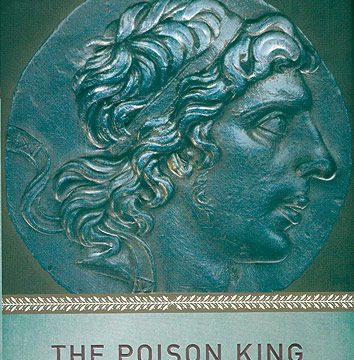

One of the fascinating characters who shaped history here was Mithradates VI Eupater (134-63 BC), King of Pontus. Mithradates was Persian-Greek, styling himself shahenshah and tracing bloodlines to Cyrus and Alexander. Pontus at various times included bits of modern Greece, Bulgaria, Russia, Macedonia, Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Iran and Turkey.

Mithradates was an implacable enemy of Rome. His career included three wars against the Romans, punctuated by multiple assassinations, alliances and intrigues.

Even by contemporary standards, the Pontus royals were dysfunctional. Mithradates’s mother poisoned his father. He poisoned his mother and brother, and married a sister to cement claims to the throne. He married many other women, killed most of them and quite a few of his children as well. He committed suicide when one of his sons finally pulled off a coup.

On occasion, he beat the Romans. He once stage-managed the genocide of 80,000 Roman citizens on the same day across various parts of the region. However, despite this, the Romans rated him a generous victor and an open-handed, just ruler.

He is now recalled more as a pioneering toxicologist than for the ups and downs of his reign. Mithradates experimented systematically, using condemned criminals, with poisons and antidotes. He’s famous for building up a personal tolerance to arsenic and developing anti-toxins against other poisons. One of his discoveries, a coagulant based on snake venom, saved his life when he took a bad wound during battle. On another occasion, he incapacitated a legion with naturally poisonous honey. Many medieval Europeans used compounds distilled from Mithradates’s formulas as specifics against poison.

The author is a historian specialising in bio-chemical warfare. She’s written an entertaining yet scholarly account of a complex personality, who combined characteristics of the savant, the mythic hero and the psychopath. Unusually, where historical detail is lacking, Mayer has used speculative fiction to fill in blanks. As it is, the known facts about this ruthless polyglot genius, who spoke 22 languages and established the basic principles of bio-warfare, are startling enough.