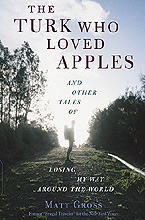

Late in his new book The Turk Who Loved Apples, former New York Times travel columnist Matt Gross argues that reading about travel offers the same rewards as the travelling itself. “Maybe it’s a little perverse for a travel writer… to suggest reading as an alternative to actual travel,” Gross muses. “But there’s something to be said for the book (and journalism) as a vector of vicarious experience.”

It’s a typically frank statement from Gross, who for years wrote the amusing and useful Frugal Traveler column. But it’s not an equation that endears the author to this reader. For though Gross expresses the desire to join the ranks of Steinbeck, Chatwin and Vollmann, chasing the fever dream of exotic romance around the world, in these pages only rarely does he emerge as the unfettered soul who not only finds travel transformative, but who can bring that story home. The book dwells too much on Gross’ interior monologues — ‘Where am I? Why do I feel so lonely? Is this an authentic experience?’ — and not enough on the quest itself. For all Gross’ globetrotting and gastronomic excess, the storytelling itself remains surprisingly and disappointingly inert. Such reservations aside, there is quite a bit to recommend this book — and to suggest that the Times and others have not been mistaken in offering Gross work.

Some of these travellers’ tales appear to be outtakes or excerpts from previously published articles, as when Gross describes the hilarious-yet-terrifying experience of trekking with balky ponies in Kyrgyzstan. Later Gross heads for Montreal with his younger brother in tow, ostensibly for the food but also to patch up a strained relationship. They find themselves at a “topless” diner where changes in the local laws mean that the formerly nude waitresses now wear bikinis.

As Gross builds to the denouement of their semi-debauchery, brother Stephen gives as good as he gets. Writes Gross: “After a while Steve spoke. ‘I know you’re my big brother and all,’ he said, ‘and you wanted to introduce me to women. But is that it?’”

Such moments unfortunately are few and far between. In the place of such small, evocative stories, Gross relies on long, discursive discussions about how persistent bouts of giardia led him to become an expert in toilet talk. From the standpoint of his column, these may be edgy or original passages, but for almost anybody who has spent time in India or elsewhere, it’s hard to stifle the yawn they induce. By contrast, Thomas Kohnstamm got good mileage out of exposing his own episodes of misbehaviour while on the job for Lonely Planet in Do Travel Writers Go To Hell? Chuck Thompson, in Smile When You’re Lying, similarly laid bare the seamy truth of professional travel writing.

So by the time Gross weighs in on the Taj Mahal — for all its vaunted symmetry and flawlessness, the author finds it “boring” — it’s next to impossible to know whether he is in on the joke. I’m guessing Gross did not want to jeopardize future job opportunities, but that means he misses his chance to show just how transcendent a good book can be. When it comes time to plan my next overseas journey, I’ll refer to his tips on travelling cheaply, but I doubt I’ll revisit the rest of the volume.