Travel is metaphorically referred to as an escape: a chance to re-imagine ourselves emboldened, adventurous, doing the heretofore unimagined. And yet, as travel becomes more and more a staid, bourgeois entertainment, we forget that leaving home was often a literal escape, less a voluntary meander and more a mad dash from a home that hemmed you in and censured your actions. And those character-building or destroying transformations occurred whether you hoped for them or not. Misfits might, in leaving home, abandon the restrictions and expectations in what Kierkegaard would call the ‘suspension of the ethical’. In their place they would find a wall-less raucous freedom, open to the abrupt behaviours from another world that signify the old self emptied.

In Lolita, Nabokov’s classic, the world’s most celebrated anti-hero Humbert Humbert sets off on an epic road trip through America. Inspired by the Nabokov family trips out west to hunt for butterflies, Humbert and Lo’s adventures with each other are set during a car trip through the desolate towns of the American interior. Humbert forsakes the moral compass provided by settled, married life to consummate a journey of sexual depravity, fumbling over his 12-year-old nymphet Lolita as her very name trips over his teeth. I imagine thoughtful, monstrous Humbert staring at Lo against an arid landscape, watching the moment unravel before him in all its inexplicable tragic mystery. Away from others, their unwitting innocence becomes a foil for the possible and suddenly we find that we are capable of condoning anything.

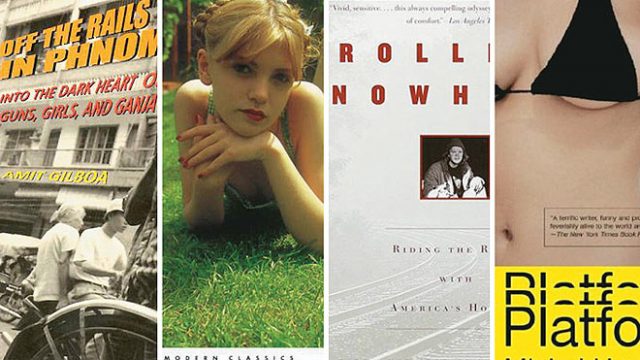

In Off the Rails in Phnom Penh, young Amit Gilboa left behind his breeding and, as the subtitle intimates, found himself “into the dark heart of guns, girls and ganja”. He reveals Cambodia for the dangerous, amoral playground it has become: its perceived post-Khmer Rouge lawlessness inviting further paroxysms of unruly behaviour from the westerners who flocked to it. The climax of the book arrives when Gilboa hires a prostitute to experience firsthand what he has been writing about. Not far behind in its fascination cum censure of such vacation misbehaviour is Michel Houllebecq’s Platform, wherein our heavyhearted protagonist finds becoming a sex tourist is the only way to protest the sexual exploitation he witnesses in South East Asia. Both find that the only way to understand what they see as the moral vacuity of these foreign lands is to surrender to the illicit.

Ted Conover left behind his straitlaced, naïve youth to aimlessly ride freight trains with hoboes and tramps across the American continent in Rolling Nowhere. These men and women (voluntarily or otherwise) set for themselves a life outside the mainstream. Searching the road and the land for their own stories, they found that the struggle to end alienation ensured a different kind of alienation. They are the permanently dispossessed, who, like sadhus, but with no promise of spiritual cleansing, chose a life of ceaseless rambling, thus levelling the harshest indictment against our settled, unquestioning life. In his violent masterpiece Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy, through the blood-drenched journeys of the Kid in the old southwest, lays plain the carnage between Native and New American, of one civilisation making place for another, the ache of the marginal to make itself known and others forgotten. This is manifest destiny in all its brutality, as men leave the world behind with the aim to remake it again.

In these stories we exult in essentially destructive, antisocial fantasies. They let us momentarily disengage not just from the present physical world, but from the moral one as well. The anti-hero shows us the lands that make us and how shallow the waters are that keep him from us.