The fluid movement of the snake – as it entered the bridal chamber and bit groom Lakhindar and retreated – was amazing. If it was not part of the puppet show, then we could have easily mistaken it for a clockwork toy. Marvelling at the magical fingers of the puppeteer handling the snake, we too clapped in unison with the local spectators. We were at Muragachha Colony, deep inside Nadia district of West Bengal and about 120km from Kolkata, to watch the puppet festival organised by the local people under the aegis of a social welfare organisation called Banglanatak dot com.

A mere dot on the map, Muragachha colony, and its neighbouring village Borboria, are home to families of puppeteers who, in the past, not only plied their craft across Bengal but also travelled to many fairs and festivals across India. Masters in string puppetry or ‘suto putul’ as it is known in Bengal, today they are trying their best to preserve this traditional folk theatre (often referred to as ‘putul natok’ or ‘putul nach’ in Bengali) against stiff competition from electronic media.

“Our families arrived in Nadia in the 1950s from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and continued with the tradition of puppet theatre,” says veteran puppeteer Ranjan Roy by way of introduction. Most puppeteers in these areas trace their roots to Khulna and Barishal in Bangladesh. According to Roy, the string puppetry practised by them probably owes its origin to ‘kathputli’ of Rajasthan but how the influence travelled to Bengal (then undivided) he could not say. “But the younger generation is not keen to pursue the family profession owing to dwindling income,” he adds.

In between watching the different puppet companies present their plays at the makeshift stage erected in the middle of the field, we took a tour of the village. Swamped in greenery, the settlement was set back from the suburban town. Rows of mud-built cottages stood on both sides of the narrow motorable road. Clusters of trees and shrubs bordered the cottages. Beyond the village boundary, we could see agricultural fields. We were also charmed by the hospitality of the locals who invited us to a community lunch that had been organised by them for the participating puppeteers and their families.

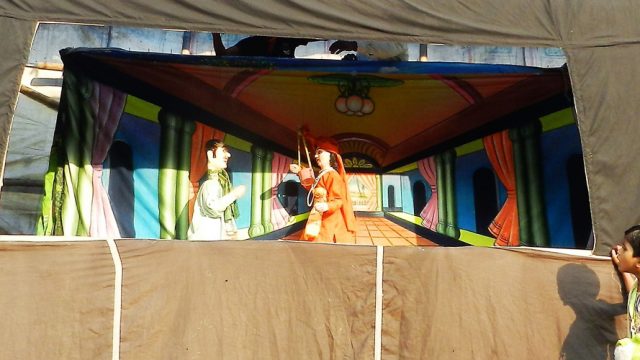

On the veranda of some of the houses we could see incomplete puppet heads and other tools of the trade lying around. These light-weight puppets hang by strings whose free ends are held by puppeteers operating from behind a curtain.

A puppet head is usually made of shola-pith and its making is a long-drawn process. Painting the expressive faces requires a master touch. Designing and tailoring the garments of each puppet is also very important. “Making a puppet is not as easy as it seems,” says senior puppeteer Panchanan Roy, “one has to breathe life into them.” Not only the puppets on stage but those used to decorate the gate and the boundary of the field spoke volumes of the artistic excellence.

The head and hands of the puppets are fixed to the body with a piece of wood or thread but there are no legs; the puppets are clothed in flowing garments which hides that aspect. The puppets have to be strong to withstand the rigours of travelling in boxes and the presentations. A team consists of a writer and narrator with singing skills, musicians, puppeteers, and assistants.

Traditionally, the puppeteers travel all over Bengal between Durga Puja and the beginning of summer — performing at various fairs and festivals and household functions – with their portable stage and dolls. Tales from religious texts and mythologies form the bulk of the plays, referred to as ‘pala’ in Bengali.

According to Nirmalya Roy of Banglanatak dot com, the need of the hour was to contemporise the stagecraft and dialogue while keeping the traditional presentation intact. They have been working with the puppeteers for the past few years and imparting training to them. Not only for entertainment but puppetry can be useful for knowledge dissemination too, feels Roy. “It can be a popular mode for conveying public awareness messages to a wide audience,” he says. Therefore, the organisation has been training these puppeteers how to make their dialogues and stagecraft more contemporary and how to create stories with relevant content. With support from WBKVIB’s Rural Craft and Cultural Hub initiative of West Bengal government’s MSME&T department in association with UNESCO, the fair was organised for the first time to spread awareness about ‘suto putul’ of Bengal. And going by the number of photographers from Kolkata and other places attending the festival, it seemed quite a successful attempt.

One of the plays we watched was the ‘Megh Brishti Pala’, a proof of how this relatively low-cost entertainment can be used to spread awareness about social and safety issues keeping its attraction intact. It was a delight to watch a couple of dancing skeletons teaching a romancing couple, Megh and Brishti, about the dangers of crossing the railway tracks when the couple decided to take a short-cut after they were late in returning home from a secret meeting.

Information: From Kolkata, Muragachha Colony (near Bagula; not to be confused with Muragachha town lying north of Krishnagar) is about 120km via Ranaghat and takes around four hours to reach; be prepared to drive through some narrow roads towards the last stretch. Those willing to rough it out, can take a Gede-bound local train from Sealdah station and get down at Bagula from where you have to take local transport to Muragachha Colony. There is no hotel or lodge here; staying with a local family is the only option. Those interested in taking lessons from the puppeteers of Muragacha Colony or participating in workshops, may contact Banglanatak dot com