The rustle amidst the leaves was more noticeable this time. It couldn’t have been just the breeze, of which there was very little anyway in this balmy environment. “This movement is typical of orangutans,” our guide Nina whispered. She had barely finished speaking when the branches moved again—this time far more definitively than just a rustle. As a coat of flaming orange emerged from the foliage, the collective gasps of a dozen or so people were drowned in the frenetic clicks of their cameras. These were people who had travelled from all parts of the world to Indonesian Borneo to catch a glimpse of man’s closest relatives in one of their last remaining natural habitats.

Our journey had commenced earlier that day when Nina had picked us up at Pangkalan Bun airport. The short taxi ride to Kumai was spent taking in instructions: do not litter, always keep out of the path of orangutans, do not touch them even if they touch you… Once in Kumai, our luggage was swiftly loaded on to what would be our home for the next three days—the top deck of a klotok, a traditional Bornean dinghy. Soon, along with our crew of three, we were on our way to the Tanjung Puting National Park for our orangutan adventure.

Nearly the size of Bali, the park spreads out in a seemingly endless canopy along the 40km-long stretch of the Sekonyer river. Boats are the only way to get in. As we settled into our klotok, we were briefed a little more about the itinerary for the coming days. Three major orangutan rescue camps operate in the region and we would be visiting the first of these today during their feeding hour.

The word ‘orangutan’ literally translates to ‘man/people of the forest’ and the camps were set up to ease the reintegration of captive orangutans into their natural habitat. Foraging for food was a key skill that these orangutans were expected to develop and, therefore, the treats at feeding stations were only meant to be a supplement and not a substitute for a meal. “If they have managed to eat enough in the wild, they won’t turn up at the feeding station,” Nina had said apologetically.

That was not the case, as evidenced by the bearer of the flaming orange coat, who now stood before us in full view. Chi-cha was one of the matriarchs of this first camp, Tanjung Harapan. Much to our delight, she was soon joined by her children—the reticent Chelsea and the showwoman Chi-na, who put on quite an act for us gawking humans. Clambering up a trunk, she deftly swung from tree to tree, pausing occasionally for breath and applause, before moving on to her next gravity-defying routine. Not one to be outshined by her own daughter, Chi-Cha too joined the fray, bringing with her not just an inimitable swag but also the newest of her children, the tiny, unsexed and unnamed youngster that clung to its mother for dear life. Soon enough, hunger trumped ego and games of one-upmanship were abandoned in favour of the sugarcane that was laid out on the feeding platform. After pulling the cane apart and gathering armfuls of it, each scurried away in search of a shady patch to savour the treat undisturbed. The power play of just moments ago was already forgotten.

Humidity hung low in the rainforest and the trudge along the wild into the feeding station, though short, had sapped our urban bodies. The plate of freshly made banana fritters that awaited us at the klotok, courtesy our cook Zuleha, was wolfed down gratefully. As the klotok negotiated its way further through the peat swamps, more delightful forest residents came to the edge of the river for a bit of people-watching. Most numerous among these were the proboscis monkeys—Tanjung Puting has the distinction of being the only natural habitat of these distinctive simians.

As we dropped anchor at nightfall, the gentle chugging of the klotoks died down and a deep silence descended over the waterways, the still night air only occasionally pierced by the nocturnal calls of the long-tailed macaque. Being some distance away from civilisation, boat captains ensure that they park within shouting distance of other klotoks. Leaving their guests to dine in the low wattage, crews got busy securing the vessels for the night, amusing themselves with raucous inter-klotok banter. Our tummies full of rich Indonesian curry and minds full of snapshots from the day’s adventures, we crept inside our mosquito-net cocoon and were soon lulled to sleep by the gentle swaying of the klotok.

Day two was heralded by the choral songs of the kingfisher and the hornbill. Tanjung Puting is a treasure trove of all manner of fauna: 50 breeds of fish, 230 varieties of birds, crocodiles, snakes and primates, the last as varied as the slow loris, langur and gibbon. But the main draw here is undoubtedly the orangutan. And so, shortly after breakfast, we set sail to catch the morning feeding at the second camp, Pondok Tanggui. There is something to be said for an early start. Being the first to arrive, we pretty much had the place to ourselves and couldn’t believe our luck as we were greeted by a mother-son duo of lazing orangutans—Linda and little Lincoln.

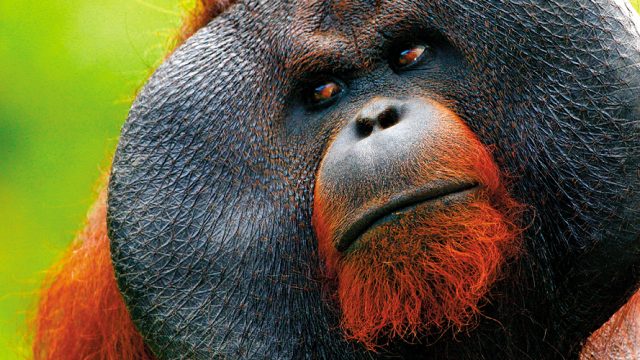

Milk was being given out at the camp and, being a favourite orangutan treat, the guides were confident that at least a couple of big guys would make an appearance. They weren’t wrong, as one of the first to show up was the alpha male of the camp, Doyok, cheek pads and all. In true headman fashion, he claimed the milk bowls on the feeding platform, leaving a bunch of females hovering tentatively at the edges. After having helped himself to a couple of vats of the white stuff, Doyok perched atop the tallest branch, surveying his kingdom and the two-legged curiosities on it.

Heading to the last camp, perched on the bow of the klotok, we were serenaded by assistant captain Ohan. As is the case with sidekicks everywhere, the onus of being chief entertainer was down to Ohan—and he proved that he was totally up to the job with his distinctive live act based on Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham!

Watching the scenery unfold with the wind in your hair and a cup of steaming coffee by your side, it was easy to lose sight of the disturbing reality that orangutans are faced with. Besides Sumatra, Borneo is the only region in the world where orangutans are found in the wild. There are about 54,000 orangutans in Borneo today and this number is dwindling alarmingly as forestland steadily gives way to palm oil plantations. Mining is the other major threat the national park authorities have to contend with.

In fact, the Sekonyer’s waters have taken on a permanently muddy hue because of the residual mercury released into the river from the mines. Interestingly, as the klotok made a right turn towards the last camp and away from the mining precinct, the water colour instantly and very distinctly turned to a clear black—purer and devoid of any mining residue. The stark contrast in water colour was a graphic indicator of things to come if the mining continues unchecked.

As the most high profile camp, Camp Leakey is often synonymous with Tanjung Puting itself. This camp was started by noted orangutan activist and founder of Orangutan Foundation International, Dr Birute Galdikas. Her unconventional methods were often questioned, but are now acknowledged as being highly successful in rehabilitating captive orangutans. Day-trippers who zip in on their speedboats for a bite-sized orangutan adventure usually skip the other camps and head straight to Camp Leakey. The near-constant human presence means that the orangutans here are a lot less reclusive and wander around freely—one cheeky young fellow even attempted to hop onto our klotok!

Having witnessed the last feeding earlier that day at Camp Leakey, we sat silently on the deck with that all-too familiar melancholy at the impending end of a holiday. The klotok had once again anchored by the riverbank and we had the best seats in the house for the spectacular light show put on by the fireflies. Taking stock of the last couple of days, we counted a total of 25 orangutan sightings. Perhaps it was the immersive nature of the experience or the fact that we were biologically so close to these apes—Homo sapiens shares 97% of its DNA with them—but this had been a wildlife trip unlike any other. Be it the adorable adolescent Ursula who came to see us off at the last camp or Chicha’s little baby, each encounter felt unique and personal. More important, however, was the realisation that these young orangutans had a right to grow up without threat—in the knowledge that the forest would be theirs and they would indeed continue to be the people of the forest.

The Information

Getting There

There are no direct flights from India to Indonesia. Malaysia Airlines and Singapore Airlines are two convenient options, flying to Jakarta via Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, respectively. From Jakarta, it is a 1hr 20min flight to Pangkalan Bun airport in Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo. Kal Star and Trigana Air fly the route daily. Their flights are usually not available to book online. ticketindonesia.info is a reliable local agency that can make the booking for you.

The Orangutan Adventure

This can only be booked through a tour company. We used wildorangutantours.com. The package is usually an all-inclusive one: airport transfers from Pangkalan Bun airport to Kumai and back, accommodation, all meals and wildlife sighting. While the 2N/3D klotok stay is the most popular option, you can opt for a shorter or longer duration. Some travellers prefer to spend one or more nights in the Rimba Lodge, the only land-based lodging inside the Tanjung Puting national park. 2N/3D package for two people: â?¹ 48,000 (October-May, excluding the Christmas-New Year period); ₹ 74,000 (June-September).

What to Pack

Binoculars

Quick-drying clothing and footwear

Flashlight / headlamp

Mosquito repellent spray

An extra battery pack for your camera

A sense of adventure!