I’ve done a few stories for this magazine that I never had any intention of doing, but this assignment — to explore Delhi’s wilderness — inspired, for some unfathomable reason, hidden reserves of unenthusiasm in me. When the story idea came up, I endeavoured to look impossibly unwilling, but the boss was — as he often is — quietly firm about it. I had to do it. Karma gone wild, I call it. I’ve spent almost a decade living in and carping about ‘saddi Dilli’. For anyone who ever asked why I was here, I had a ready answer: “The mountains are so close!” I spent as much time as a salaried individual can in them Himalaya, and spent the rest of the time railing that I wasn’t getting enough holidays. Delhi was wild, I agreed, a wilderness even, but not like, you know, the Serengeti, more like Gangs of Wasseypur.

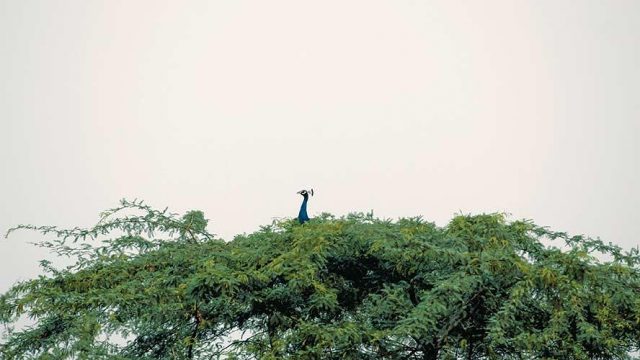

To be fair, I’ve often been struck by the stark beauty of the Aravalis, the flight of parakeets across the sky at dusk, the crash of a nilgai in the undergrowth in Jawaharlal Nehru University, the slow sprouting of fresh leaves on the trees around India Gate or the sight of a peacock staring derisively down at me, daring me to finish the final pitch at the climbing wall of the Indian Mountaineering Foundation. Even so, it seemed to me that I didn’t know enough about the city I lived in. After all, I hadn’t even been to the massive Jahanpanah City Forest, barely ten minutes from my house. So I decided to start my wanderings there.

Delhi’s bioregion is usually divided into four types: the kohi (hilly tracts), the bangar (arable plains), the khadar (sandy riverine) and the dabar (floodplains). The kohi encompasses the ridge that runs sporadically through the south, west and north of the city, an extension of the Aravalis. Jahanpanah, which forms a 550-odd-acre buffer roughly between Tughlaqabad in the south-east, Chirag Dilli in the north-west and GK II in the north, is something of a transition zone, belonging primarily to the kohi but also to the bangar. Late in the afternoon, a few steps from the hellish Alaknanda-GK-II road lands me in another universe. Car honks give way to birdcalls, exhaust-fumes to fresh air. A few joggers pant up and down the perimeter of the forest. Parakeets protest loudly, treepies, babblers and redstarts chitter in the undergrowth, while a woodpecker sits zen-like on a power pylon.

Jahanpanah is a managed forest — there are many ornamental trees here, planted by the Delhi Development Authority — but as I move deeper into the thickets down the narrow paths that crisscross the forest, the indigenous trees show up. Deciduous trees like kareel and ber, ronjh and khair brush against creepers, huge bushes and cacti with large, phallic appendages. A bountiful monsoon has left the forest bursting with health, and it seems that the birds understand this. Far from the main walkways, I sit beside a chain of shrubs and watch families of sunbirds and babblers go about their business. At first, they warily stay out of sight, but the longer I wait, patient and still, the bolder they get, until they’re buzzing around me, oblivious of my presence. In the slanting sunlight, the leaves turn a hundred shades of riotous green, and the chatter of bird call rises to a fever pitch. Then the sun starts sinking, and the colour starts draining fast; the forest falls eerily silent.

Smitten by my experience, I head off to another part of south Delhi to Sanjay Van, an old forest in Mehrauli and a major link in a chain of greenery extending from the parks south of the Qutub Minar to JNU and Vasant Kunj to the north-west. Curiously, many of Delhi’s forested areas stand on sites associated with Delhi’s history. Jahanpanah had been a part of Muhammad bin Tughlaq’s Delhi, while Sanjay Van had been home to the Delhi of the Tanwars, the Chauhans and the Khiljis. Lying just off the traffic-choked MG Road to Gurgaon north of old Mehrauli, Sanjay Van is a wilder forest than Jahanpanah. A part of the south ridge, it is divided into two sections: a partly managed medicinal forest and an Aravali forest. I make my way to the ruined ramparts of Qila Lal Kot for a better view of the forest canopy. The sights are quite spectacular. Qutub Minar and the dome of the bulbhulaiya stand tall out of the dense greenery to the south, while the forest stretches away as far as the eye can see to the north-west, with some water towers on the skyline marking JNU’s location. Closer to the north rear up the buildings of the Qutub Institutional Area; it’s quite a sight.

Within the enclosure of the Lal Kot walls, a colony of egrets was hanging around, and this abundance of prey drew in a golden jackal. I stumbled upon him purely by chance as I descended from the fort’s ramparts. For a split second, jackal and I were face to face, absolutely still. Then he turned tail, darted over a rise and vanished. I apologized for upsetting his supper as a couple of babblers hopped about on a nearby tree, hurling harsh invective. I followed the path around the perimeter of the ramparts through the forest. The intense heat had brought out an army of large black ants. They followed a straight-line trail for about half a kilometre, busily hauling food to a hole in the ground, the caching for winter well and truly under way. Although Sanjay Van has a rich ecology, nowhere is the unique problem faced by Delhi’s indigenous trees more evident than here. Vilaiti Keekar, a Mexican mimosa that was introduced by the British in 1915, has proliferated alarmingly, even edging out many of the region’s indigenous trees like the dhau. Sanjay Van has lots of them, their twisted barks running through the forest like trees on steroids, imprisoning the surrounding fig trees and other indigenes in a proliferation of branches. These trees, much like the similarly British-introduced Chir Pines in the Himalaya, are a menace to the ecology of the region.

But they do look quite dramatic, especially when framing, say, a Khilji-era gateway — or a nilgai calf, such as the one I faced off with in Sanjay Van. Young and gangly, all spindly legs and knobbly knees, he showed no alarm at my approach and even headed my way. Then he stood there for the longest moment, as if lost in reverie, but then something clicked in his head and he bolted ungainly into the undergrowth.

If Sanjay Van is the wildest city forest, the central ridge forest is arguably the most degraded. Although quite large, and very atmospheric from a passing car, the forest is in crisis. Surrounded by densely populated areas like Karol Bagh and Jhandewalan, and proximate to infrastructure projects like roads, flyovers and the metro, it is being eaten alive by encroachments. An illegal Army polo ground and its stables pollute a large chunk, while a certain notorious godman’s ashram nibbles away at another end of the ridge. The nearby diplomatic areas and five-star hotels have done their bit to deplete the already shaky water-table.

One forest that is thriving is the Asola Bhatti Wildlife Sanctuary. Again, the bountiful monsoon rains may have been playing tricks with my mind, but the forest seems a lot more mature and lush than I remember it from my last visit five years ago. In its 22nd year, Asola too has it rough, ringed as it is by real estate, urban villages and air force stations. And yet, it teems with life: its trees are growing tall and there are nilgai in the thickets, cranes in the sky and peacocks perched on the canopy; woodpeckers rat-tat-tat away, and an assortment of Indian tree pies and weaver birds, jungle babblers and sunbirds dart in and out of flowering thickets. A forest’s beauty is defined as much by its smallest inhabitants as by its largest. I sit and watch a tiny, emerald spider of exquisite beauty patiently build a silvery web. A peacock cries in the distance, and several others echo the call, and suddenly the forest is reverberating with their harsh cries. It stops as suddenly as it started, and the chirpy static resumes. A nilgai looks balefully at me, a large black-naped hare twists away with the speed and agility of a rustabell. I wish the inhabitants well and set off across the state border to the hidden forest of Mangarbani.

About an hour’s drive south from Asola over horrendous roads leads you deep into the northern fringes of the Aravalis. Scrub and thorn forests predominate and the land rises. This part of Haryana is infamous for the mining nexus that has illegally carved open large chunks of this ancient range. But Mangarbani, for now, is different. It isn’t a notified forest or a sanctuary, but this remote valley has been able to preserve a bit of the Aravalis in pristine condition. Fed by a seasonal stream, it is sacred to the memory of Gudariya baba, a mystic who has a striking domed shrine deep inside the forest. For a few hundred years now, the villagers of nearby Mangar, Bandhwari and Baliawas have kept the forest free of grazing to abide by Gudariya baba’s wish that no harm should come to his forest. This has resulted in a thickly wooded valley, about a 100 hectares in area, filled with trees — like the dhau, the kala siris and the salai — which have all but disappeared from Delhi. These trees stand around in wild profusion, and the dhau, with its wayward trunks and phantasmagoric branches, is the closest thing I’ve ever seen to an Ent in real life. Tree pies and babblers seem to love it here, as do parakeets, with the dhau providing the perfect home. The forest is also home to jackals and nilgai, which I didn’t see in the noonday heat, but is overrun by peacocks. We couldn’t take five steps without a crashing sound in the dense undergrowth around us, as a peacock scrambled away with a squawk. Clumps of peacock feathers are lying around: these are the preferred offerings to Gudariya baba. We climb out of the valley and up to the northern lip of the enclosing ridge. Here, the forest cover thins a little, and giant boulders appear — knobbly rocks almost 150 million years old. I feel a shiver through my spine just to imagine such antiquity. And yet, there they stand, beloved of geologists and quarrymen, some of the oldest thing on the subcontinent. From up here, Gudariya baba’s shrine looks even more dramatic. Sunbathing lizards scamper for cover. It’s all indescribably peaceful, and I find myself praying that it stays this way.

Much has been written about the death of the Yamuna, and the river as it passes through Delhi is certainly a sorry sight. However, it says something about the resilience of the wild that even in such toxic surroundings, the flood plain continues to support an astonishingly wide variety of fauna. To find out more, I head to the Yamuna biodiversity park in Wazirabad. Run by a bunch of scientists led by Faiyaz Khudasar, the 457-acre wetlands is in fact an ecological experiment. As Faiyaz tells me, it is an attempt to artificially recreate a riverine environment which in the long term becomes a self-sustaining bioregion. After about a decade of work, just a patch of the park is self-sustaining now, but with complex environments it takes time.

The park’s main attraction is the large lake in the middle. Complete with reed thickets and an artificial island, the lake draws a large number of migratory birds in winter. When we get to the lake’s edge, the island is occupied by a couple of darters. These are large and gawky birds, with long necks that earn them the colloquial name of snake-birds. To me, they look like the missing link to dinosaurs, as one plunges with a huge splash into the lake, fishing. The reeds too teem with life. Storks alight on branches and then take off again. Little weaver birds, looking like scruffy children foot-dragging their way to school, tweet and hop from reed to reed. Meditating bee-eaters sit stock still, until they spy a bee far above, at which point they launch themselves into an elegant gliding swoop to pluck their prey from the sky before alighting on a branch and proceeding to bash the bee to death. Fascinated by this display, I ask Faiyaz about the health of the Okhla Bird Sanctuary, the only one of its kind within Delhi. He smiles and says that even though the Yamuna is horribly degraded, the sheer size of the wetlands in Okhla provides for a patchwork of habitats. So even though Okhla may be too polluted to provide food to the avian community, it remains a great site for nesting.

I keep this in mind when I accompany a group of seasoned birders to Okhla Bird Sanctuary at dawn the next day. September, when I visit, is a sort of transition month before the winter migrants start arriving, but you can still catch the early bird. So the talk is that of early migrants, juveniles, plumage and other bird jargon which is quite quaint to my ears. The people I’m with apply themselves with a vengeance to the task of spotting birds. One of them, Peeyush, tells me that there are essentially two types of birders: those that are genuinely interested in birds and their habitats, and those that are trophy hunters, devotees of the exclusive photograph, at any cost. My companions, led by long-time bird enthusiast Kanwar B.Singh (armed with a telescope), are firmly in the first camp. Despite it being the off-season, so to speak, there are plenty of birds around. Ducks aren’t plentiful but they’re there; there’s even a flock of flamingos in the distance. Painted storks fly elegantly over the marsh reed thickets, and lapwings step daintily on legs that would put a model to shame, pausing to pick out insects from the water. Bee-eaters are legion, swooping with deadly accuracy. I follow one right into the sun, fascinated by its plumage. A bronze-winged jacana is spotted, and everyone strains at their binoculars to catch a glimpse. It turns out to be a juvenile.

The reeds here grow man-high, and like the shifting, surreal nature of wetlands everywhere, it’s quite a thrill to walk over a path that’s somewhere between solid and liquid. Just as I’m negotiating it gingerly, a quiet, meditative man pulls me up with a sharp intake of breath. “Look to your right,” he whispers, “what a beauty!” And it indeed is, this tiny red bird, with a drip of perfect white spots on his back. As we watch, the red avadavat dances about on the reed stalk, engrossed in picking the requisite kaash phul (reed flowers) for his nest. He seems oblivious of our presence as he tugs and hops slowly away into the maze of reeds.

I go home in a daze, up to my beak in Delhi’s wilderness. Come evening, I make my way to Jahanpanah, to say hello to the sunbirds. I feel like a prodigal returning home.

The information

Jahanpanah City Forest

The most accessible point to this large wilderness area is the gate opposite Don Bosco School on Alaknanda Road. Entry is free; open from dawn to dusk.

Sanjay Van

Situated in Mehrauli, it’s a thickly forested area of the south-central ridge. Enter from Aruna Asaf Ali Marg, the Qutub Institutional Area or from MG Road beside the TB Hospital. Entry is free; open from dawn to dusk.

Hauz Khas

A landscaped park for the most part, it’s still a great place to go tree-watching. Open from dawn to dusk, next to the Hauz Khas Village; entry is free.

Central Ridge Forest

This thickly forested area of the central ridge of the Aravali is situated behind Raisina Hill. Enter from the Buddha Jayanti Park. Open from dawn to dusk.

Northern Ridge Forest

The smallest of the ridge forests, it’s also something of a heritage walk. Open from dawn to dusk.

Yamuna Park

The park near Jagatpur village in north Delhi isn’t technically open, but those interested in biodiversity or in birding can contact park authorities at 011-27616569 for guided walks. Opens at 9 am.

Asola Sanctuary

It can be accessed from the Surajkund Road opposite the Tughlaqabad Fort. Open from 10am to 4pm.

Mangarbani

The sacred commons of the village Mangar hosts the best-preserved Aravali forest in the Delhi region. A rough road branches off south from the Gurgaon-Faridabad toll road at the Mangar police station to Mangar village, from where a dirt track leads to Mangarbani. Respect villagers’ feelings and don’t litter the habitat. Sure, you can drive much of the way, but it’s best to approach the shrine and the forest by foot.

Sultanpur

This bird sanctuary, roughly 15km from Gurgaon on the Gurgaon-Farrukhnagar road, is great for sightings of migratory birds in winter—despite the creeping encroachments.

Okhla Bird sanctuary

Located just off the DND Flyway to Noida, it comes alive in winter when migratory birds come in droves. There are a couple of machaans for birders. Open from dawn to dusk; entry fee Rs 30.