Don’t feel too guilty if you don’t know what Junagadh is all about—not many people do (which can be quite a blessing). Many places have rich, complex, multi-layered histories, but for sheer individuality, era after era, story after story, no place can beat Junagadh. It is now every tourist’s dream oxymoron—a quiet city!

Eccentricity embellishes the folklore here. One favourite is that of Sultan Bahadur Shah who valiantly, perhaps illogically, defended his kingdom in the 16th century by opposing the Mughals and the Portuguese. Fearing a Mughal victory, he is said to have despatched exotic treasures, priceless jewels and even the ladies of his harem out of Junagadh, intending to follow if Humayun won. Except the ships fell into the hands of the Sultan of Turkey and never returned.

One of the 200 states of Saurashtra never absorbed into British India, the Nawab of Junagadh, Mahabat Khan III, opted to accede to Pakistan post- Independence. This was an unexpected move, given that almost 500 km of Indian Gujarat separated the jaunty ruler from his political preference. His majority non-Muslim population was not amused either. Exiled in his own fiefdom, he had to flee—but not without his dogs (an obsessive canine lover, he was famous for getting his dogs married in elaborate public ceremonies!). Legend has it that he left his spouse behind and took his dogs instead. The records are silent on the matter of the dogs but they do tell us that, on the plane, with him went a veterinarian.

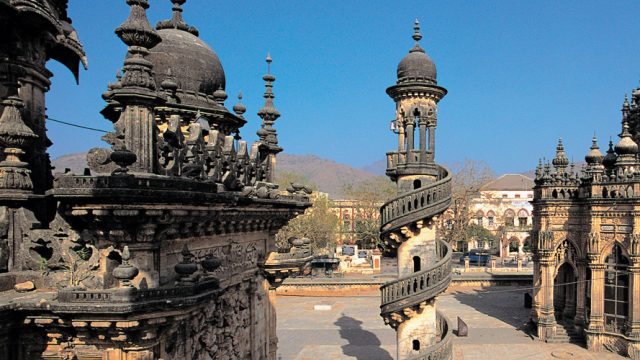

Walking about Junagadh is like taking a quirky history lesson that got left out of the syllabus—may be because it refused to take itself too seriously. Venice meets Lucknow here, where stories and structures from the past come together and meld into a thick, rich, incredibly exotic brew. Where else would you find architecture that is straight out of a fairy tale, the dome of a tomb that looks like a UFO and the most unconventionally beautiful mosque possible? Junagadh is the ultimate post-modernist pastiche in many ways—and it was so long before anyone had heard of PoMo. History hides here and it’s only because no one has come seeking it.

Junagadh is a walled city with the central Dhal Road running through it. Every other road in this town is either twisting or narrow or both. It is best to start with Bahauddin (or Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel) Gateway, across the railway station.

The most bizarre of all Junagadh’s buildings must be the 19th-century Mahabat Maqbara, built by Bahadur Khan III for his father Mahabat Khan II. The structure, a mixture of Indo-Saracenic, Islamic and European architecture, is awesome. A board next to it calls it ‘an excellent example of post-medieval Islamic architecture in an Indian environment’. Next to it is the elaborate Bahauddin Maqbara (built in 1878-92) with its elegant corkscrew towers straight out of a fairy tale. Request someone from the neighbouring Jumma Masjid to open its doors

In the 19th-century Junagadh Palace, near Diwan Chowk, is the Durbar Hall Museum with an unusual collection of artefacts associated with Junagadh Nawabs. It has chairs and thrones arranged to imply an imminent durbar session. On its walls hang portraits, including two of Mahabat Khan III with his dogs wearing jewelled collars. Another section has ornate brass howdahs and palanquins. There are elaborately sculpted female chauri (plumed fan) bearers being swallowed by fish. There’s also a macabre weapons collection, including a walking stick with a small pistol built into its handle.

The bazaar in front of the Junagadh Palace celebrates late 19th-century kitsch with Gothic arches, standing next to Awadhi style gateways, and surmounted by a European clock tower. The 19th-century Jumma Masjid, with its Gothic arches, chandeliers and colonial ceiling fans, can be easily mistaken for a ballroom, if it wasn’t for the mimbar. Its multi-coloured pillars are a bit of an eyeful. Near Khapra Khodia lies the 19thcentury Maqbara of Naju Bibi, an ambitious and powerful begum who briefly ruled over Junagadh in the name of her teenage son. It is fashioned in a distinctly indigenous Junagadh style and the dome actually looks like something akin to a UFO.

Next to Naju Bibi’s tomb is Barah Shahid, the graves of 12 martyrs —soldiers of the Tughlaq Sultanate of Delhi who died in a failed ambush against the Rajput ruler of Junagadh. The graves are housed in an oblong, early medieval building.Visible from Naju Bibi’s maqbara are the 2nd-century CE caves of Khapra Kodia. An erstwhile Buddhist monastery, also referred to as Khengar’s Palace, it is a rock structure carved into a series of cells, passages and stairways.

Uperkot, the sprawling ancient fort that dominates the city, is layered thick with myths. Believed to date back to the reign of Chandragupta Maurya, it gives Junagadh its name—‘Old Fort’. Its history speaks of 16 sieges. For example, the 11th-century ruler Rah Khengar is remembered for his defiance of Sidhraj of Patan—he married Sidhraj’s bride-to-be, Ranakdevi. Insulted, Sidhraj lay siege to Uperkot. Local historians claim the siege lasted 12 years, after which Sidhraj stormed the fort and killed Khengar. The Navghan Vav (stepwell) in the fort dates from Khengar’s time. The fort was apparently abandoned between the 7th and 10th centuries CE before being discovered again.

The approach of the fort is through a strangely narrow gateway with an ancient archway, a fine example of the Hindu torana. The top of the fort is flat and crossed by paths linking the principal sites. Inside, on the western wall, are two colossal cannons, Neelam and Manek. Neelam Tope was cast in 1531 in Egypt, and is 17 ft long. It is beautifully wrought and intricately detailed (and was probably incredibly destructive in its prime). The inscription on it makes its purpose clear, “to fight the incursive Portuguese, who are the infidel enemies of State and religion”.

Close by is the 15th-century Jama Masjid of the Uperkot fort, built from the remains of a former Hindu palace, said to be that of Rah Khengar and Rani Ranakdevi. A little further are the Buddhist caves, some dating back to 2nd CE or perhaps even earlier. Coin hoards of the Saka Kshatrapa kings, found during excavations, hint at links between monastic Buddhism and worldly trade—monasteries often tended to serve as the repositories for the safekeeping of merchants’ money. Due to the profusion of western Kshatrapa coins found here, it has been surmised that there was a mint.

The caves have an elaborate cistern system for water. Greco-Scythian style carvings beautify the lower hall, three storeys underground but open to the sky! To the east of the caves are two breathtaking stepwells. The first is the Adi-Chadi Vav, named after two slave girls of Rah Navghan who are said to have constructed it in the 11th century. This looks as much a natural wonder as a manmade one. The rock is cleaved by a narrow, wind-eroded staircase that descends 100 ft to a broad well. The second, Navghan Vav, plunges even deeper to 170 ft. It’s said to have been completed in 1060 CE. It has rock-cut circular stairs going to the bottom, with occasional apertures in the shaft for light. Not for the faint-hearted, the vertiginous or the weak-legged! The Uperkot fort also has a reservoir from the time of the Junagadh Nawabs—with a pumping station still in use and even a few visiting water birds.

GOING TO GIRNAR

Girnar Hill, rising 3,000 ft over the otherwise flat plain of Sorath, dominates the horizon and the imagination of Junagadh. The flag of Nawabi Junagadh preserved in the Durbar Hall has a sun rising over a mountain (Girnar) and a lion (from Gir), the emblems of the state. At the foot of Girnar Hill is the rock on which Ashoka’s 14 edicts in Brahmi script are carved. Girnar also attracts Hindu and Jain pilgrims to Junagadh.

One gets to the historically important Jain temples climbing 3,700 steps up the cliff, past some caves, after a thick deciduous forest at the base of the hill. The steps were built in 1889, after funds were collected by floating a lottery. There are shops for refreshments on the way, and the view is breathtaking. At over 1,500 ft, after crossing many garish new constructions, you come to what looks like a 16th-century fortress clinging to a cliffside. This is the Jain temple complex of Girnar.

There are 16 shrines here, with the biggest dedicated to the 22nd Tirthankara, Neminath, dating back to the 12th century. Architecturally, the most striking is the Vastupla Temple with an image of Mallinath. It is actually three temples joined together. There are elaborate carvings on the exterior and interior. The complex has an air of tranquility about it, increased by the sound of the bells tied to the shikharas of the temples.

This temple complex is only halfway up Girnar. There are many temples and kunds all the way to the top, all of 7,000 steps, including the Bhairon Jap (from where people would jump off to be reincarnated as kings in the next life!). Great views of the Junagadh city and the plains beyond. Fortuitously, as enterprise is never too far from religion in India, there are masseurs waiting to attend to your aching calves and thighs when you descend from the mountain! The ideal time to climb up the hill is just before sunrise, in the relative absence of pilgrims. Photographing the idols is not allowed

The town does not offer too much for visiting shoppers. There is a local market called panchatadi which has shops selling saris and daily provisions. On Azad Road, there is a Khadi Gram Udyog where one can pick up handmade products native to Gujarat that are marketed by the Khadi and Village Industries Commission.

Where to Stay

Most hotels in Junagadh city offer basic facilities. The Lotus Hotel (Tel: 0285-2658500; Tariff: ₹1,250-2,500) is close to the railway station. Hotel Girnar (Tel: 0285-2621201; Tariff: ₹300-1,000), run by Gujarat Tourism, is a fairly reliable budget option—it is opposite the RTO Office, Majewadi Gate. Other budget options include Hotel Vishala (Tel: 2631599; Tariff: ₹1,000-2,000), Hotel Shree Paramount (Tel: 2623893; Tariff: ₹500-1,500) and Hotel Indralok (Tel: 2658511-14; Tariff: ₹1,200-1,850).

Where to Eat

Geeta Lodge, close to the railway station, has the most amazingly tasty and filling Kathiawadi thalis, a flavour distinctly different from Gujarati thalis. Not to be missed and not heavy on the pocket either. Watch out for specialities like khasta kachori (lentil and spices-tuffed puri), undhiyon (marinated vegetables and a gram flour savoury cooked in a mud pot), the rich lasania batata (garlic-flavoured spicy potatoes), the filling bajra rotla (unleavened bread made with pearl millet), gatte ki pulao (steamed and deep fried gram flour in flavoured rice), chaula methi dhokla (steamed dish made of black-eyed beans) and masala bhaat (spicy rice). Desserts include the special Kathiawadi kheer and malpua (milk-flavoured sugar pancakes). Sagar Restaurant, on Jaishree Road, is good for Kathiawadi food as well.

AROUND JUNAGADH

GONDAL (64 km)

Halfway between Rajkot and Junagadh, Gondal was said to be the only princely state in Saurashtra that did not tax its subjects in the 19th century. During Bhagwat Singhji’s rule in Gondal (1884-1944), railway lines were laid, a school was built and a nine-volume history of Aryan Medical Science was written. It appears that the income generated by freight trains passing through the region raised sufficient revenues for the state. To get a fair idea of the history of Gondal and its fascinating maharaja, start at the Naulakha Palace. Have a look at the impressive Vintage Car Collection of the Gondal royal family.

SOMNATH (89 km)

The drive to Somnath, south of Junagadh, is as interesting as the destination. It passes through Vanthali (16 km), where you will see a number of 1940s Fords being operated as taxis! Just short of Somnath lies Veraval, a port with a history of maritime trade. Even today, it is a major ship building centre for dhows. The wood comes from Malaysia.

Between Veraval and Somnath is the Bhalka Tirth, where Krishna is believed to have died. The site is disappointingly modern and kitschy. But drive past the wooded graveyards along the beach, and you can imagine a forest of reeds here, planted by a curse—as the legend goes. It is said that the reeds turned into maces, with which Krishna’s drunken Yadav clan slashed each other to death. Horrified, Krishna ran into the forest, where he was killed by a hunter’s arrow.

Somnath has been a pilgrimage spot for long. It could be because of the Triveni Ghat, the confluence of three rivers, Hiran, Kapil and the mythical Saraswati. The Somnath Temple stands by the sea, its wall thrashed by waves. The first temple is said to have been built by Somraj, the Moon God himself. The current temple was built in 1961 after excavating the remains of the former temple at the site.

The Somanth Temple faced many Muslim raids after Mahmud Ghaznavi’s attack in 1026; it was rebuilt by Hindu devotees. The irony is that while local Muslims have died defending Somnath, and Hindu rulers have plundered pilgrims by taking gifts for the deity. Sculptures and remains from the earlier temples are now housed in the Old Museum.