The rheumy-eyed priests watch impassively as raucous boys play marbles in the pillared courtyard of a temple in Ahmedabad. The ash-smeared old men don’t say a word about the adolescent antics; they barely seem to breathe as they recline on a bench. They could be 80 or 100 or as old as Kala Ramji Mandir itself — a 350-year-old structure painted with vegetable dyes in a fading shade of verdigris. Both priests and temple exude the mellow ambience of a bygone era that pervades the pols in the city’s old quarter.

Marvels of urban traditional architecture – now threatened by development – Ahmedabad’s 6,000 pols are self-contained neighbourhoods consisting of clusters of houses laid along narrow streets. Each has a name and a distinct identity (often related to the community and caste of the residents), and its own public courtyard, chabutara or bird feeder, and a public well. The oldest, Muharat Pol, was built in the 1500s.

For almost five centuries, the pols’ network of gateways (the word ‘pol’ derives from the Sanskrit word pratoli or gate), guards’ cabins, cul-de-sacs and secret passages kept its residents safe during riots, wars and periods of social unrest. But a more recent threat is less easily overcome: carved wooden houses are now being converted into cinderblock buildings, and charming chabutaras into makeshift, pop-hued shrines.

The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) in 2000 started to place name plaques at the entrance to the pols to raise awareness about this architectural tradition among residents and visitors. It also conducts daily heritage walks since 1997 to showcase the art and culture of these unique neighbourhoods.

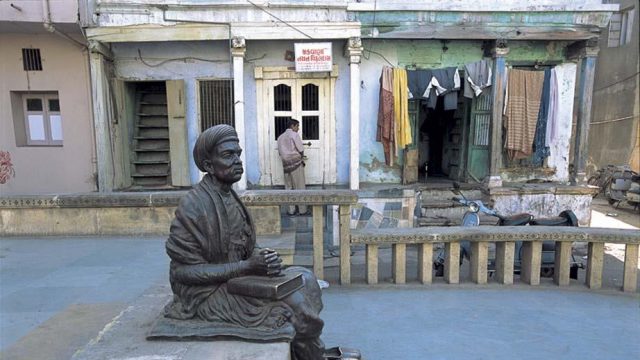

At Kavi Dalpatram Chowk, a sculpture of the Gujarati poet, after whom the public square is named, contemplates a tulsi plant across the street. A reproduction façade marks the spot where his house stood in the 19th century. Then, as now, animals and birds were integral to the daily life of residents. A well-preserved 100-year-old chabutara, with a granary cleverly built into its base, attracts the descendants of the pigeons the poet perhaps fed. The exterior walls of some buildings contain high niches, rimmed with stucco moulding, in which parrots nest. In the porches of temples, squirrels swing on tin feeding trays.

The pols’ temples are spare in size but ornate in design, and each has its own secrets and treasures. At one Jain temple, Queen Elizabeth, playing a sitar, is ensconced above a lintel, while lions lounge on either side of her. Another, the Jagvallabh Mandir, has its sanctum sanctorum in the basement; the 700-year-old marble idols of Tirthankaras, adorned with pure diamonds and rubies, were brought from the holy site of Palitana in Saurashtra. In the temple’s backyard, a 400-year-old tank is still filled with rainwater collected from the roof and conveyed by pipes to the underground cistern.

The houses in the pols are typically compact and low-ceilinged, but some are prodigal of rooms as well as open space. Almost a century old, JaiSinghbhai no Haveli requires renovation, and cobwebs strangle an old-fashioned water pump at its entrance. But the decrepit air accentuates the grandeur of its 40 rooms and the romance of aerial bridges between structural wings. The 180-year-old Harkunvar Shethani ni Haveli contains 60 rooms, most of which open on to interminable pillared balconies, supported by the longest carved wooden bracket in Ahmedabad.

The pols seethe with colour. Bright greens, yellows and oranges cover every pillar, plinth and spire of the Swaminarayan temple in Kalupur, built in 1822. Contrast is a cherished principle of design — a mint-green house has yellow shutters, a white house has royal blue glass windows. The stalls of Manek Chowk display polychromatic heaps of mukhva or after-dinner mouth fresheners, and the otherwise bland Shri Samvegi Upasrai Mandir has violet pillars.

The busy colour patterns are complemented by the buzz of mundane activity. “Manjula behn!” a vegetable seller cries as she negotiates a crooked street, and the customer so addressed promptly appears in a first-floor window. Elsewhere, through an open door, an old man can be seen teaching the Gujarati alphabet to a little girl in thin pigtails and thick kajal. At the book market near Fernandez Bridge, vendors starting their workday slam ledgers onto tabletops.

The sacred and the profane — religion and commerce — commingle in the pols, as seen in the reverence of shopkeepers for their livelihood and in the ubiquitous juxtaposition of shops and shrines. The clamorous, cobbled road at Fernandez Bridge leads to the Jumma Masjid and the adjacent tombs of Sultan Ahmed Shah I, who founded Ahmedabad in 1411, and his descendants. It comes as no surprise to find that Rani no Haziro, the hallowed burial site of royal ladies, now contains the city’s hotspot for trendy teens — Fashion Street.

Contact: Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, Mahanagar Seva Sadan, Sardar Patel Bhavan, Danapith, Ahmedabad, Tel: +91-79-25391811 to 25391830, e-mail: info@egovamc.com