A small group of men had collected outside the closed door of the Kailash Bar and Restaurant, the only liquor outlet in Padum, Zanskar’s largest settlement. “Tashi,” shouted someone. “Tashi!” “He isn’t here.” Just then Tashi arrived on a motorcycle. He shook his head. “The stock is over,” he said. “Don’t know when it will come.” The supply of mutton hadn’t arrived yet either. “The pass has just opened, and now the DC has to fix the rate before it can be brought here,” I was told. The BSNL mobile service had been out of order for over a week, and no one knew when it would be repaired. Most hotels were still closed. And there was electricity for only three hours in the evening. But no one was complaining.

The thick winter snows had retreated to the tops of the mountains that surround Padum. A dense carpet of grass studded with yellow and blue flowers was emerging from the dry and dusty Zanskar plain. The Penzila pass had opened and Zanskar is who’d spent the winter outside were returning. Men in their ochre Ladakhi gonchas had emerged from their houses to drink tea at roadside dhabas, while women with children clinging to their backs chatted in the fields. During the day the sun was bright and warm. The ephemeral summer had finally arrived. Everyone in this little outpost, 230 bone-rattling kilometres from Kargil, was celebrating.

We’d flown to Srinagar, and then driven to Kargil. By the time we left Kargil the next morning the main market was bustling. Kebabs were cooking on the coal fires of roadside stalls; old men with creased faces, wispy goatees and grey turbans stood drinking tea on street corners; and music blasted from a riot of Tata Sumo taxis that jostled for passengers on the main street.

Leaving the melee behind, the road emerged into the valley of the Suru river, a green swathe between the dry rocky mountains. Poplar and willow trees lined the roads. Emerald green fields of peas and barley, fringed by yellow spring flowers, spread out from small villages.

After Sanku the road started climbing rapidly. So rapidly that at Panikhar you could almost reach out and touch the angular, snow-covered Nun-Kun massif, which towered above the village. Tongues of snow now reached down gulleys, almost licking the road. The tree cover which had been thinning had now disappeared, and the grass here looked out tentatively from the thawing earth. A small white chorten indicated Rangdum, the first Buddhist village.

Then the climb to the 14,500ft-high Penzila pass started. Sheer crags of snow-covered mountain reared up on both sides of the road, which had shrunk to a narrow furrow of brown in a sea of white. The car’s engine struggled against the altitude, belching vast amounts of black smoke, while we braced ourselves against the cold, adding another warm layer to the existing two. A chorten marked the top of the pass. A few hundred metres from the pass, the enormous Drang Drung glacier, source of the Stod river, came into view, a vast jagged river of ice snaking its way between the mountains. Far below us, the road levelled out, running straight out across the start of the Zanskar plain.

The speck of green in the distance turned into a village of stone houses, narrow lanes, cows, horses and donkeys. A man was walking down the road in traditional homemade leather shoes, two arrows sticking out from the back of his shirt. “Drukchen Rinpoche, the head lama of Hemis is visiting Zanskar. A three-day archery competition starts in Padum tomorrow, after the Rinpoche’s speech,” said a lama who’d hitched a ride with us. A few more villages passed by. The mountains moved apart. After 200km of ups and downs, the plain ahead seemed to stretch lazily, luxuriously, eternally out. The road cut across the plain, skirted the edge of a mountain, and came to an abrupt halt at a kilometre-long stretch of small shops and houses ringed by towering snow-peaks: Padum.

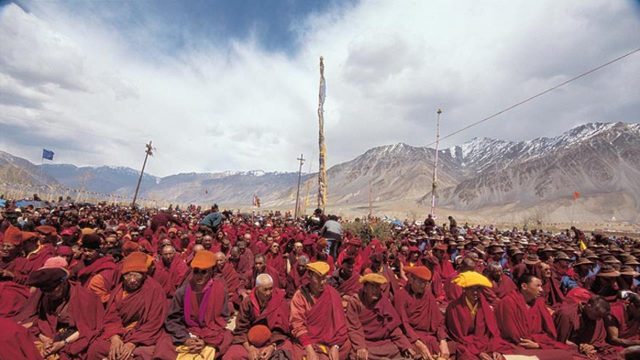

The large dusty courtyard of the Photang (the Dalai Lama’s guesthouse), a square two-storeyed structure a few kilometres from Padum, was crawling with people. Old men twirling prayer wheels shuffled slowly alongside young men in jeans and women wearing elaborate silver jewellery and flowing turquoise-studded peraks. Entire families from across Zanskar had come, children and picnic baskets in tow. The Rinpoche was delayed, and would only arrive in an hour. People, many of whom were meeting for the first time after winter, settled down to talk in any shady spot they could find.

At 1.30 a tungchen (long trumpet used by the lamas) let out a rumble from the roof of the Photang. The first of a long procession of chomos (nuns) and lamas entered the compound. Sandwiched between them, sheltered from the mid-day sun by a tall parasol, walked the Rinpoche, waving to the crowds that bowed before him. “I wanted to walk through Zanskar as an anonymous monk,” said the Rinpoche addressing the crowd, “but many people have joined me.” A clap went up. The chomos started chanting and the crowd joined in. Soon I could only hear snatches of what the Rinpoche was saying. Bread was being distributed among the lamas. The villagers had pulled out their thermoses and were drinking gur gur chai.

I wandered off in search of my horseman and guide, who had vaguely mentioned that he’d meet me here. Tsering was circumambulating the Photang, prayer beads in hand, when I spotted him. He broke into a toothless grin on seeing me. His wrinkled face, dark glasses and broad-rimmed hat gave him the look of an ageing Western actor. “Juley, juley,” he said clasping my hand. We went over our schedule one last time.

At nine the next morning I heard the tinkling of a bell coming down the road. Tsering had shed his goncha for jeans and a jacket. “This is Sta,” he said stroking his sleek brown horse, “He’s two years old.” Leaving the market we got on a footpath between barley fields. The fields gave way quickly to a dusty trail. Sta was in a playful mood, nibbling on Tsering’s backpack and chewing on his arm, as Tsering smiled like an indulgent father. The tinkle of Sta’s bell set our pace. Our destination, the village of Karsha, was visible two hours away, perched at the bottom of a mountain slope. A small explosion of green in this formidable brown landscape.

Mutup Chospel was away at the archery competition in Padum, when we reached his house at Karsha, but his wife and children were home. His house is part of a circuit of homestays created by the Snow Leopard Conservancy. The aim is to provide villagers alternative sources of income, in the hope that this will bring down the retaliatory killing of snow leopards (the snow leopard or shen is a major predator of livestock). The room for guests, which had been added recently, was on the third floor, and had stunning views of the mountains above Padum. It was simple but clean. A deliciously cooling snack of thick bread (tagid tsurkur) made from atta, lassi and chhang with a dip of curd with a kind of spinach (tangtur) was brought up for me.

Above his house, clinging to the hillside, was the majestic maze of buildings of the Karsha gompa, the largest in Zanskar. The crumbling ramparts seemed to grow out of the brown rock of the mountain. Narrow alleys squeezed their way between prayer halls and monks’ quarters. The blowing of a conch signalled dinner time. In the chamba dukhang, the oldest prayer hall in the monastery, a three-storeyed Maitreya image radiated a deep and benign calm, while a fierce wind rattled the windows. “This,” said the young monk who’d been showing me around, pointing to a large gilded castle in a glass case, from which many intricate spires rose, “is the abode of Mahakala. It’s where we go when we die.”

Tsering was at the door early next morning. “We’ve got a long walk ahead,” he said. Leaving Karsha, the trail ran on the plain above the sunken gorge of the Zanskar river. As we walked towards Zangla, the ancient capital of Zanskar, the valley narrowed. Scree slopes cascaded down from high jagged edges of rock. Distances became deceptive. Chortens many hours distant looked like they were a few kilometres away. “Look,” said Tsering pointing to a pugmark in a wet patch of sand, “sankhu (Tibetan wolf).” “Two of them passed this way in the morning. And a lomdi (jackal) was behind them. What the wolves leave, the lomdi eats. That is why they’re brothers.”

We’d barely walked a couple of kilometres when we met another horseman. He’d apparently seen the wolves pass by early in the morning, and had rushed to retrieve his horses from a field where he’d left them to graze. Tsering and he got into an animated conversation. Then Tsering pulled out a plastic bottle filled with chhang. They took turns at taking swigs. In between, Tsering opened Sta’s mouth, and they peered at his teeth, nodding gravely. I looked at the river, and shuffled my feet. But the rules seemed to require that the chhang be consumed before we could move on. Twenty minutes later, with a final gulp, the other horseman stumbled backwards. “He’s a drunkard,” laughed Tsering, turning to me, “Finished most of my bottle.”

A few hours later the ruins of the Zangla fort appeared high on a hill above the village. We crossed the fast-flowing green-grey Zanskar on a rickety wooden suspension bridge. We’d been walking for almost nine hours. The clip-clop of Sta’s hooves as they kicked up puffs of dust, the tinkle of his bell, Tsering’s occasional grunts and the sound of the river surrounded us like a cocoon. Sta was tired, stopping at every stream to drink water.

I climbed up to the fort the next morning. The building was a square three-storeyed structure, with narrow balconies that looked out from the top floors. This was where half of Zanskar was once ruled from. It was also where Csoma de Koros, the 19th-century Hungarian Tibetologist, stayed and worked for a year in 1823. A narrow passageway led into the fort. Many rooms had fallen, but it was still possible to climb up to Csoma’s small dark room on the third floor. The wooden beams in the hall outside his room were black with age, and sparrows nested in cracks in the wall.

Tsering, Sta and I were back on the trail later that afternoon. Sta was in a playful mood again. The short track to Pidmo village ran just above the road. Tsering was singing a slow Zanskari song. The first terraced fields of Pidmo appeared. It was warmer here than Padum, and the crop of barley and peas taller. Twilight had turned the fields a dull gold. Donkeys and horses were being herded back into their enclosures. It was time to say goodbye to Tsering and Sta. They would head to Pishu, while I would take a car back to Padum. I patted Sta on the forehead. “Juley,” said Tsering, giving me a big hug. Then he got onto Sta and trotted off into the evening.

Padum was quiet when I got back. The ‘First CEC Cup Archery Tournament’ was over, and the officials who’d come for it had left. That day, the clouds which had been hovering around the mountaintops came down early, turning dusk to night. Prayer flags fluttered furiously in the breeze. The lights of the Karsha gompa spread up the mountain at the other end of the plain, while those of village houses at the base gleamed like a cat’s eyes in the darkness. The first slivers of moonlight touched the snow peaks, moving slowly downwards. A gaggle of men was standing outside Kailash Bar and Restaurant. The booze still hadn’t arrived.