The Shanku, as the Himalayan wolf is known in Spiti, is found in parts of India, Tibet and Eastern Nepal. An endangered species today, it is considered to be one of the earliest species of wolves, traceable to 800,000 years ago. In an attempt to sight this elusive animal I set out for Kaza in the Spiti valley, escaping Delhi’s summer heat for the cooler climes of the Tibetan Plateau.

Kaza, at first glance, is a veritable Disneyland of colours. Bright red, green, yellow roofs greet you as you descend into the shadows of the valley. I was a little disappointed with Kaza, but to give it its due I must add that it is a good place to base yourself for treks and tours to other parts of the valley.

We were met at the office of Spiti Ecosphere, an ecotourism outfit that works with villagers in Spiti, by Sunil and Norbu, the latter a former Mr Spiti and an excellent source of local legends and tales. His ancestors served as amchis, physicians to the kings of Spiti. Every generation passes on its skills to the next, along with a vast reservoir of tales and legends that gain and lose detail with time and with every telling.

The first half of day one was spent acclimatising. I sat on the steps of Spiti Ecosphere’s office with a hot cup of tangy tsering tea (made from the skin of the seabuckthorn berry). Spiti Ecosphere, set up by Ishita, Parikshit and Sunil, aims to create a self-sustainable economy and conserve the natural habitat in the region through its various programmes, which includes the cultivation of seabuckthorn apart from other ecotourism initiatives.

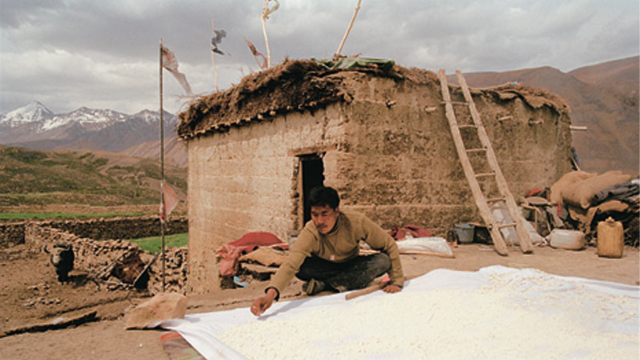

Our first destination on the wolf trail is Langza, in the Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary. A pleasant looking lady, wearing a printed headscarf around her head in the traditional manner, welcomes us. We are shown into a neat room with choksas (long low tables) arranged neatly along the walls. The lower half of the house is for the livestock and the upper half divided into rooms, with the kitchen being the largest and central space in the house.

After a simple meal of dal chawal we walk towards the Rewonk Phu area on our maiden attempt to track the wolf. Sunil, who’s accompanying me on this trek, tells me that the wolves have given birth to cubs and should have moved away from their lairs. Rewonk he explains is rabbit in Boti, the local language, and their caves are often confused for those of wolves. In order to protect their livestock from the wolves, the locals are known to have smoked out wolf cubs from caves, weaning them away from their mothers, and letting them die. As more forestland under the state governments Nautod scheme is allotted to locals for agriculture, the few wolves retreat into the mountains, stepping out only under cover of darkness.

We walk up a small nallah. Sunil picks up stones and inspects them closely. “The area is rich in fossils,” he tells me. I look at the round stone in his hands, cracked on the sides; it opens easily like an oyster’s shell to reveal a beautiful fossil on the inside. “These are sold for Rs 40-50 in markets in Kibber and Kaza.” I take a photograph of the fossil and leave it by the nallah. We’re walking on a magical layered bed of history somewhat akin to the years etched in the walls of the mountains that surround the area.

“Wolves have been here,” Sunil says, pointing to the scat on the earth, as we walk along the ridge, “Not very fresh, maybe a week old.” Lhote, the cook, is accompanying us and walks ahead to check on the caves up ahead. The area is far greener than I had expected, rocky in places, sprinkled with patches of wild flowers.

“Wolf!” I cry out and immediately Sunil and Lhote’s eyes turn towards my pointing fingers. Sunil pulls out his binoculars. “It’s a fox,” he exclaims. I look through the binoculars, disappointed of course but happy to have seen something of the wildlife in the area.

The evening is spent with a family at a local home stay. We sit around the chakthap (rectangular stove with a long chimney that extends to the roof) as a member of the family deftly stuffs boiled potatoes and local spring onions into small pancakes, turning towards us intermittently and smiling. We’re eating momos for dinner. The men are drinking chhang, every now and then checking the television to see if Kumkum is on air. Sunil informs me that a wolf has been sighted near Gyara and we decide to skip Kaumik and head towards Gyara the next day.

Our day begins with freshly baked round tirik bread and a cup of yak butter tea. Tsering, a local guide with Spiti Ecosphere, joins us on our journey and ensures that our backpacks and gear are loaded on the donkeys and the lone chiru that will accompany us.

It’s a steep climb up to Chu Ulsa where we stop to rest. There is little vegetation on top and the seasonal nallah is still dry. Langza, ‘headquarters of the devtas’, is visible in the far distance as we walk up. There is a strong belief in local devtas or deities who solve people’s problems through gurs or intermediaries. Norbu and Sunil had both told me of an instance in nearby Poh where the local devta prohibited the cutting of juniper trees for incense. The faith in these demigods is unshakeable and on every Li Dui, or day of the devtas, villagers assemble to pray to the local devta.

We camp near a small stream in the Gyambaley area. We’ve been walking for a few hours and the altitude is now beginning to take its toll on me. I decide to rest for a few hours sipping chai in the shade of the kitchen tent. Sunil decides it’s best for me to take it easy and visit the wolf caves in Chulcha the next morning.

The walk to the Chulcha area the next day is pleasant; walking downstream, we check for more fossils as we head towards the wolf caves. The caves are off the main path and we stop below a rock face. Leaving our bags on the dry riverbed we walk up the steep path behind Tsering. The caves are deep and Sunil mentions that some may even accommodate two body lengths. Checking a few caves further up we head towards Gyara.

Gyara, at 4,465m, is a doksa (temporary settlement) of Demul village. A few men mounted on horses are driving the yaks further down the valley. A handsome grey yak has been arranged for the following day for our journey to Balangri Top, often described by locals as a world visible only to avtari lamas (lamas who are reincarnates) — it’s replete with everything from monasteries and people, to cats and dogs.

We spend the night camping on the periphery of Gyara. I can hear dogs barking in the distance. “There must be a wolf in the vicinity,” Sunil smiles, sticking his head out of the tent. It’s too cold and the thought of stepping out in the night cold to check for wolves is less than appealing. I sit up to listen to the barking and eat my soup of pakchels (conch-shaped balls made from wheat) and yere, a local vegetable.

An animal is pushing against our tent. Half expecting to see a wolf I step out and instead find a donkey nuzzling against the sides of the tent. Sunil drives the donkey away. Our yak, tied to a stone, stands still on one side of the open field seemingly in the same position that we had left it the night before. Perhaps he’s meditating, I think to myself.

We walk up around the side of Dey Gurtuk, the magnificent chokula (mountain) standing tall in front of us. My yak lumbers along slowly. The saddle is hard and I dismount to walk the last few kilometres to Demul. I can see blue sheep grazing in the distance. After a short break in Demul we begin our steep ascent towards Balangri. This is possibly our last chance to see the wolf, as we will head for Kaza tomorrow. There is wolf scat in the area but no wolf in sight. Reconciling myself to this disappointing inevitability I look ahead to Balangri, still a distance away.

From the top, the valley below looked deathly, with steep cliffs outlining the sharp fall. The last 40m up to the top were very steep. I could see prayer flags fluttering in the wind. Sunil had already made himself comfortable at the far end of the top and was now calling out to us to join him.

I stood at the mouth of the ledge looking straight ahead at Sunil and walked the last few steps towards the edge, sitting down as Sunil made space for me at the narrow edge. Comfortable, I craned my neck to look at the views around me. Sunil and Tsering point out villages to me in the distance and try to identify the 20-odd villages that it is possible to see from Balangri. It’s hard to believe that during Namgen, a local harvest festival (August 15), horse riders race up to Balangri Top to offer prayers for a good crop.

Back in Demul, we visit Amchi Chundui, Norbu’s father, who has just returned from Kaza. Sitting in the large dining room he recounts how his ancestors moved to Demul, his hands stoking the fire as he talks. “We lived around the Phibuk area in a village now known as Yul Shikpo,” he tells us, slowly sipping his arra (a refined form of chhang). According to local legend one of the villagers of Yul Shikpo lost his dimo (female yak) and came looking for it, reaching Demul as we know it today. The villagers sat there for a while before heading home. Later in the year, the dimo was missing again and the villagers found her in the same place as they had earlier. This time they found barley growing in the area which to their surprise the dimo did not touch. “Our village then was facing a water shortage and, considering this ominous, our ancestors decided to relocate to present-day Demul.”

It is a clear night as I step out onto the terrace of Norbu’s ancestral home. Looking into the starlit darkness I know the wolf is out there, living possibly in the invisible realm of Balangri, choosing to reveal itself only to those it wishes to. Maybe I’ll have better luck the next time I visit Spiti.

The information

Getting there

The valley is accessible from two sides, via Manali across the Rohtang Pass (763km in all from Delhi) and via Shimla (790km in all from Delhi). In the winter months, when the Rohtang Pass is closed to traffic, Kaza is accessible via Shimla.

Contact

Spiti Ecosphere offers a range of tours in Spiti — from wildlife trails like the wolf trail, to jeep safaris, yak safaris and tours with an emphasis on the cultural aspects of the region. There are two fixed departures in the month of July, leaving Delhi on July 13 (Rs 38,400, all inclusive, Delhi to Delhi) and July 26 (Rs 37,500). Tours can also be customised to meet your interests and time.

Tips

> Kaza has most basic facilities including Internet access, though it can be slow.

> Most mobile networks besides BSNL do not operate in the area.

> The last ATM facility on your way to Kaza via the Rohtang Pass is in Manali.

> Make sure your car’s tank is full before you head towards or away from Kaza.

> May to October is the best time to visit Spiti. It’s bitterly cold at any other time of the year.

Altitude sickness

Altitude sickness can be a major problem in Spiti. It is essential to take adequate measures to acclimatise to the high altitude. Drink water and do not over-exert yourself on the first days of your stay. Diamox or acetazolamide is often prescribed for altitude sickness but it is best to consult your physician to ensure correct use and dosage. Kaza has a hospital, which is equipped to deal with altitude sickness.