Antique rock crumbled under my feet and bounced down the side of Ranthambhore Fort to the sprawling, dusty forest below. I walked into the skeleton of a house broken into by the roots of trees, and standing on a carpet of grass, looked out of a thousand-year-old window. Ranthambhore is magic. The place is full of romance and intrigue — tenth century ruins smothered by roots, herons sharing lakes with holy men and a million myths about Raja Hamir and the glory days of the ‘impregnable’ fort. The fort’s fall, along with that of the one at Chittorgarh, is what is credited with breaking the spirit of the legendarily resilient Rajputs and the establishing of an undisputed Mughal Empire in India. Locals still visit a Ganesh temple here, as did their ancestors. And like them, they must walk through tiger forests to do so.

My pilgrimage was longer. Leaving the madness and grime of Mumbai late one evening, I arrived to the bright light, cold air and red brick of Sawai Madhopur Station the next morning. If all journeys are metaphors, this is an especially poetic one, the scene changing from Maharashtra’s city slums at dusk to benign open scrub and field of the Desert State at dawn. And as I moved out of mobile coverage area, I found myself shedding all urban angst, counting Indian rollers, blue jays, tree pies… and actually noticing three distinct shades of blue in the sky. Once at Sawai Madhopur, the short drive from the station to the park was equally un-creasing; apart from the busy market place at the start of the journey, it was all camel carts, heaps of guavas and that dazzling mirror work on the outfits of Rajasthani women sauntering by.

Once inside the main gate, a canopy of trees provided shade and the air was at least a few degrees cooler. My open-top gypsy added whiplash wind to the experience, and at the ticket counter I was greeted by Ranthambhore’s omniscient presence — a tree full of langurs. Scavenging on the left-overs from pilgrim picnics, screeching for attention, somersaulting, they landed with unnerving thuds on the tops of tourist buses, and in one case, even urinated to the disgusted delight of school kids.

Ranthambhore is a popular holiday destination and, in winter (the best season weather-wise), it is often full of noisy tourists on an obsessive search for tigers, talking noisily while waiting for an audience with The King. It is hard not to hope for tigers when you’re in Ranthambhore, but there is something tainted about tracking them with walkie-talkies and harassing them with a constant barrage of gawkers. The trick to getting the most out of the park is distancing yourself from the maddening crowd and being satisfied just breathing tiger air. Suddenly then, everything about it becomes thrilling.

On my first day in the park, while watching cormorants dry their wings on a bare tree in the middle of Rajbag Lake, someone in the next vehicle swore they had spotted a tiger peeping through the window of a ruin far on the other bank. Everything looks like a tiger when you’re desperate to see one, I said, but around the bonfire at Ranthambhore Bagh (a lovely tented accommodation) that night, a photographer confirmed reports of a young tigress hiding her cubs there. The next day, back at the same spot, while a sambar stag foraged in the water, I had stripes on the brain. About a quarter of an hour later, for no apparent reason, the sambar stumbled out of the lake, antlers festooned with vegetation, and dashed off. The mother tigress had begun her languid amble towards me long before I had noticed her. Making her way across a sliver of land in the water — literally a catwalk across the lake — she stopped a stone’s throw from my vehicle, crouched down and began to drink. Close enough to see her whiskers quiver, the slapping of her flat pink tongue against the water was the only sound I heard for what seemed to be an eternity.

Finally, she crossed the path in front of us and walked ahead, letting us follow her in our vehicle for at least 20 minutes down the road before disappearing into the foliage (probably leading us as far away from her cubs as she could). Tigers, my guide informed me, liked walking on the Forest Department’s un-tarred roads because they’re soft on the paws. As a result, the roads provide opportunities for incredible tiger sightings. Slightly peeved with the six vehicles blocking the path in front of me first thing the next morning, I was forced to join the fray waiting for their promised tiger (a tip-off from a forest guard.). There was no way any wild animal was going to make an appearance with those many people around, I thought. I was wrong. Not only did the tiger make an appearance, he was on a hunt. Slipping silently into the tall grass just off the road, he crouched, waiting. There was no prey as far as anyone could see, but soon there was a wretched yelp, immediately thwarted. A few minutes later, out came the gorgeous predator awkwardly dragging along a cheetal (almost as big as himself) by the neck. There, right on the road in full view of a few dozen awe-struck humans, he sat down and, half-hidden by the grass, began to feast.

Not all trips to tiger reserves are this rich, I know. Even forests guards don’t see a kill in action very often — tigers are only successful once in 20 tries — and at the end, it’s down to luck. Leaving the park a few days later, as I drove past Rajbag, past Jogi Mahal, past Gomukh, past the soaring cliff face (where eagles nest and leopards hide), past the last racket-tailed drongo and dhok tree, I turned around just in time to see the ancient fort looming like a vision borne of opiate excess… Leaving Ranthambhore is like leaving a vital organ behind. You have to come back for your heart.

About Ranthambhore National Park

Once the hunting grounds of the maharajas of Jaipur, and later the British, this area, spread over an expanse of 392.5 sq km, was declared the Sawai Madhopur Wildlife Sanctuary in 1955. In 1973, it was declared the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve under Project Tiger. An area of 274.5 sq km from within the Tiger Reserve was notified the Ranthambhore National Park in 1980. With the launch of Project Tiger in 1973, the National Park began to be protected in earnest, and as the forest returned to health, aquifers in the area began to replenish, to the benefit of surrounding villages.

The surrounding areas of Keladevi Sanctuary (674 sq km), the Sawai Mansingh Sanctuary (127 sq km) and the Kualji Close (7.58 sq km) were consolidated and added to the National Park in 1992, bringing the spread of the reserve to an impressive 1,174 sq km.

The park’s royal past, when kings and nawabs gathered here for the annual tiger shoot during the Raj, coupled with high tiger sightings, have made it an attractive destination for the country’s visiting dignitaries. In 1961, a hunting party was organised at Ranthambhore for Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh. Rajiv Gandhi visited the reserve armed with a camera in 1986 and the former US President Bill Clinton came here in 2000. The most recent visit was that of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in May 2005 following the furore over Ranthambhore’s poaching incidents that had followed so closely on the heels of the Sariska tiger scandal. The current official count of tigers at Ranthambhore stands at an uninspiring 26. Given the size of the park, it seems like a remote possibility to come across the apex beast in its own habitat. But travellers to this prime wildlife destination have repeatedly reported their satisfaction with, and in some instances, even their marvel at the Ranthambhore experience. The reason is that the park is best known for its almost assured tiger sightings as the tigers here are reputed to have become fearless of human company and are often sighted during the daytime. The denizens of the park continue to fight a battle for survival as the problems of poaching and cattle grazing by neighbouring communities and villages remain unresolved. If the tigers of Ranthambhore are to be saved from the fate of Sariska’s tigers, a more concerted effort needs to be made by forest officials and wildlife lovers.

The tiger guru

Anyone who has been to Ranthambhore has heard something about the eccentricity, devotion and passion of Fateh Singh Rathore. He joined the Indian Forest Service in 1960 and spent many years as Field Director of Ranthambhore. He was one of the few handpicked by Kailash Sankhala, the then director of Project Tiger, to be part of the first Project Tiger team. Widely acknowledged as a ‘tiger guru’, his knowledge of the striped cat is legendary; he has an uncanny ability to predict where the tigers are and many have witnessed him ‘talk’ to them!

Needless to say, his single-minded drive to protect the park was not always popular. Once, infuriated at the bar on grazing cattle in the protected area, villagers ambushed Fateh Singh’s vehicle, beat him up and left him, bloody and unconscious, for dead. He was soon up and defending the reserve again of course, amidst plenty more threats to his life. In 1983, Fateh Singh was awarded the International Valour Award for bravery in the field.

Today, Fateh Singh has retired from the service, but not from his tigers. One of the best known warriors in the global effort to save the Indian Tiger, he has been awarded the status of honorary warden of the park. He lives about 10 minutes from the Ranthambhore gates at ‘Maa Farms’, where, among other things, he has started a school for local kids — not surprisingly with an emphasis on wildlife conservation.

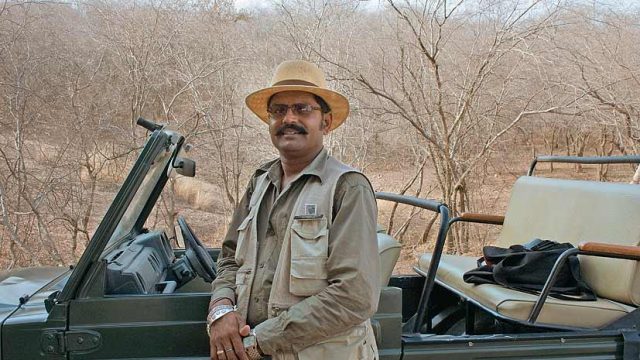

If during your visit to Ranthambhore, you see a solitary figure standing upright in an open vehicle in khaki jodhpurs, aviator sunglasses, cowboy hat over a balding pate, twisting the ends of a huge Rajput moustache to a fine point, consider yourself lucky. You would have just spotted Ranthambhore’s most fearless resident!

The information

Getting there

Rail: Nearest railhead Sawai Madhopur (15 km/ 1/2 hr) has good connections on the Delhi-Mumbai line. Most resorts will arrange pick-up/ drop from the railway station. Or you can hire a taxi for about Rs 250, or an autorickshaw for Rs 100, to your hotel.

Road: The drive from Jaipur via Tonk and Sawai Madhopur to Ranthambhore is 10 km longer than an alternative route via Kanota, Dausa and Lalsot, which is a bad road. Since private vehicles aren’t allowed in the park, it might be better to go by train instead to Sawai Madhopur.

Tip

If you fly into Jaipur, you can hire a car and drive a couple of hours to Ranthambhore, but a direct train from Delhi or Mumbai is advisable. It’s a lot cheaper and also less complicated and a much more interesting journey.

Orientation

The birdwatching opportunities here, especially around the lakes, are legendary. You will see large herds of herbivores, cheetal, sambar and nilgai, and also find feline pug marks scattered in the sand around dilapidated chhatris. You can also spend endless afternoons crocodile-watching by a lake. Also visit Jogi Mahal, located near a shelter constructed by Raja Hamir for a sage.

The entry point is on the Ranthambhore Road, about 10 km from the railway station at Sawai Madhopur. It passes through the Missradara Gate to the Ranthambhore Fort (the latter lies within the park’s precincts). The Ganesh Temple is within the fort, and the Jogi Mahal lies at the foot of the fort. The Ranthambhore School of Art, where you can do some shopping, is located on the road that leads up to the park.

Park entry fee Indians Rs 524, foreigners Rs 914, including park entry, vehicle and guide fee. Cameras are still free, video Rs 400. Park timings 7-10 am, 2.30-5.30 pm (subject to change from time to time, so get an update when booking your trip)

Things to see & do

Despite its popularity with tourists, there is something primal about being in and around Ranthambhore. While truckloads of visitors may seem annoying at first, it is, if you can yourself see it that way, what makes the park not an artefact, but rather a very real place where ancient ruins, nature and contemporary village life make layers of history almost tangible. Don’t miss the fort and wake up early to witness its beauty at sunrise.

Tiger safaris

The highlight of your Ranthambhore experience is the 31/2-hr jungle jeep safari for tiger spotting. No private vehicles are permitted into the park; book a tourist jeep safari online at rajasthanwildlife.in well in advance (at least 60 days before), especially in high season, or through your travel agent. Bookings were earlier handled by the Forest Department but are now done online by RTDC. Two jungle safaris a day, following defined tourist trails (seven routes for Gypsys, five for Canters), are on offer currently. Jeep movement along these trails are strictly monitored to ensure the least interference to animal movement. Only 20 Gypsys and 20 Canters are allowed, per trip, to move on the routes.

Canter Indians Rs 393/ 431, foreigners Rs 783/ 821 for diesel/ petrol vehicle Safari timings 7-10 am, 2.30-5.30 pm

Ranthambhore Fort

This ancient citadel is situated almost exactly at the meeting point of the Vindhya and the Aravalli hill ranges. The fort, after which the National Park is named, is thought to have been built in 944 AD and is considered one of the strongest forts in the country. It was occupied by Raja Hamir for many years until the siege by Allaudin Khilji’s army in 1301 AD forced the Rajput king to surrender. Legend has it that women committed jauhar, or self-immolation, to escape from enemy hands. It can be tiring to walk up to the fort’s ramparts but the view of the park and its three lakes from the top is worth the effort. Locals believe that the mortar used in constructing the fort was mixed with the blood of brave warriors! Its legendary strength comes from this mixture, it is thought.

Ganesh Temple

Dedicated to Lord Ganesha, this temple is located inside the Ranthambhore Fort, within the precincts of the park, about 15 km from Sawai Madhopur. The Ganesh Chaturthi celebrations draw large crowds, including tourists and locals alike, to the temple. Entry to the fort itself is free so as to allow devotees easy access to the temple. They arrive in droves on Wednesdays and on the chauth of every month.

Jogi Mahal

Located at the foot of the fort, Jogi Mahal is home to the country’s second largest banyan tree. The Forest Rest House (FRH) at Jogi Mahal offers stunning views of the Padam Talao, which is awash with water lilies. Tourists, however, are no longer permitted to stay in this rest house.

The marketplace

Close to the railway station, this is where you can find traditional Rajasthani bangles made of glass and lac and knick knacks that can be good souvenirs.

The Ranthambhore School of Art

Situated on the road that leads up to the park, it is definitely worth a visit. The wonderful wildlife paintings here, many of which feature the tiger in its natural habitat, have been created by local artists. The school contributes towards tiger conservation — a good enough reason to buy stuff here instead of opting for the slightly cheaper paintings you may find elsewhere around the park.

Where to stay & eat

There are a number of hotels to choose from to fit every budget, most of them scattered on Ranthambhore Road. Rates vary greatly on and off-season, and it is advisable to book in advance. You will have to depend on the hotel where you are staying for food; many of them throw in meals with their stay packages.

Run by the Oberoi’s chain, Vanya Vilas (Tel: 07462-223999; Tariff: Rs 44,500-53,000) on Ranthambhore Road is lavish, with prices to match. Coming back to Vanya Vilas from a drive through the forest is always a bit of a shock. Liveried staff welcomes you back with cold, scented towels and the temperature in the luxury tents is always right regardless of the desert outside. Get a massage or work out at the gym, and though you may wince at their well-tended rolling greens and swimming pool in the midst of perennial drought, the food here is truly heavenly.

The Sawai Madhopur Lodge (Tel: 220541; Tariff: Rs 19,000-26,000) is run by the Taj Group of Hotels and has a restaurant, bar, swimming pool and travel desk. It also arranges safaris.

Sher Bagh (Tel: 252119-20; Tariff: Rs 28,750) is located 3 km from the gate. Run by polo player Jaisal Singh, who has known the park well from the time he was a child, this fancy establishment offers 5-star comforts. Tiger Den Resort (Delhi Tel: 011-27570446, 09811200094; Tariff: Rs 7,150-8,150) is just 2 km from the park on the Ranthambhore Road and has a restaurant, a pool and a souvenir shop. It offers jeep safaris and nature walks. The price includes stay and meals. Tiger Moon (Telefax: 252042; Tariff: Rs 1,850-4,425), in Sherpur-Khijlipur, has 32 cottages, a dining hall, wildlife library and a pool. Castle Jhoomar Baori (Tel: 220495; Tariff: Rs 3,900-6,900), formerly a hunting lodge of the Maharaja of Jaipur, is located on the top of a hill and offers a great view of the park. There are 12 rooms here and a multi-cuisine restaurant. Ranthambhore Bagh (Tel: 224251; Tariff: Rs 2,837-6,141) is run by Aditya and Poonam Singh and has a casual atmosphere with great home-cooked food. Rooms with basic facilities are available, but the tented camp (each with electricity and attached bath) is highly recommended. RTDC’s Hotel Vinayak (Tel: 221333; Tariff: Rs 1,900-4,000), located on Ranthambhore Road, near Vanya Vilas, has 14 rooms, a dining hall and houses the RTDC Information Centre.

When to go

The park is closed from July to September. It opens once again from October to June. November to February is the best time to head here, when bonfires make chilly nights enjoyable and the sunny T-shirt weather enables day-long journeys without the stress of summer heat. March, April and May are oppressively hot with the desert ‘loo’ — hot and dry winds that blow during the day — baking everything in its wake. On the upside, the dry summer months allow for some fantastic animal sightings through the bare vegetation.

Contact

Wildlife/ Forest Dept office

Chief Conservator of Forests/ DFO

Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve

Sawai Madhopur

Tel: 07462-220479/ 766

STD code 07462