Ten minutes into Tehran, I have my first encounter with Hafez. I bring it upon myself by asking the taxi driver about poetry. It’s all the encouragement he needs. He whips out his copy of the Divan of Hafez from the glove compartment, balances the open book on the steering wheel and starts reciting sonorously. Fourteenth-century poetry accompanies us as we barrel down a long straight concrete highway at 90km an hour, heading for the rush-hour crush of downtown Tehran. The words I catch are familiar from Urdu poetry, of wine and the beloved and gazelle eyes. At the end of the journey, he inscribes his copy of the book and gives it to me, as a yadgar to remember him by. Poetry and generosity — they follow me through the rest of my trip. As the sun goes down on Isfahan, young and old gather under the arches of the bridge, using the resonant acoustics of the vaulted space to practise singing.

Three days later, I’m in Isfahan. Isfahan is physically, architecturally, an astonishingly lovely city. The distinctive blue mosaic tiles, which cover every surface of the monumental mosques of the city, look like they were applied yesterday and not in the time of Shah Abbas in the 17th century. A river meanders its way through the city, with many old pedestrian bridges crossing it; its banks are lined by chinar trees that shade playgrounds and walkways. The most beautiful bridge across the Zayandeh is the Pul-e Khaju. It’s beautiful not just because of the blue mosaic edging its two levels of arches or the intricately painted balconies on its upper course, designed for those who would cross the bridge to stop and rest and look out at the views. It is beautiful because it is alive. Hundreds of Isfahanis gather here every evening, spiky-haired teenagers playing volleyball, girls in hijab riding BMX bikes, families sitting on the steps and cooling their feet in the water. And rising out of the arches under the bridge, heart-piercingly, hauntingly sad songs, blending with and rising above the sound of rushing water. As the sun goes down on Isfahan, turning the Zayandeh to a sheet of flame, young men and old gather under the arches of the bridge, using the resonant acoustics of the vaulted space to practise singing. They sing Hafez, of course. And the volleyball players and BMX riders gather to listen. And visiting tourists weep.

Last year, a friend tells me, the government stopped the Zayandeh upstream of Isfahan for reasons unexplained. The city was in mourning and they wrote elegiac poetry to the river they had lost. And there was much rejoicing when the river came back, its water flowing again under the spans of the bridges. In Iranian cities, poetry flows like water and the water flows like poetry. It is a harsh, dry landscape for the most part, stark dashts and bare mountains up to the very edges of towns, but you’d never know that while in a city.

In an inversion of the usual, the wilderness is barren here and the cities are green. Channels of water run down the main streets of towns, fountains play in parks and public squares and everywhere, everywhere, there are wonderfully tall, broad-leafed trees like the chinar, often growing out of the channels. Even in a city like Yazd, out on the edge of the Dasht-e Lut and the Dasht-e Kavir, with summer daytime temperatures hitting 50° Celsius, the water still flows. But here, to escape evaporation losses, the qanats run underground, marvels of medieval engineering that continue being built and used today. They even have a water museum in Yazd, in which they document all the traditional methods of excavating and maintaining the underground channels, and the technologies of harvesting and sharing this precious water. It’s kind of strange, but wonderful, to have a museum dedicated to something that is not yet dead.

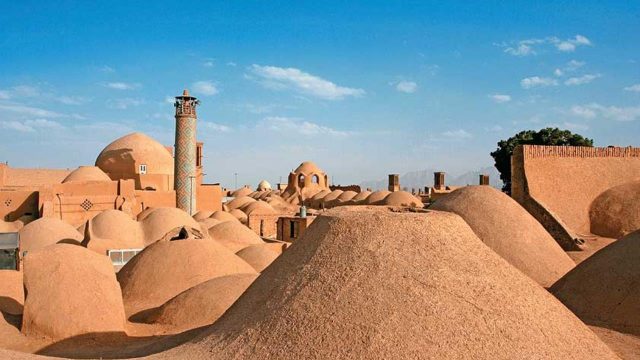

Yazd is a fairytale city, a mirage rising out of the desert, so strange and improbable it is. I reach shortly before noon and already the air is blistering hot, in a way that makes May in Delhi feel positively breezy. It’s especially shocking after the coolness of Isfahan, just a few hours away by road. The taxi driver recites poetry, of course, a sh’er of his own about small hearts (dilha-e tang) leading to war in the world (jang jang). And in a few minutes we are in the middle of old Yazd, with large domes and tall towers and spires rising out of a dun, mud-brick city. The towers look a little like chimneys, large enough to be the chimneys of kilns, and I think to myself, this city doesn’t need more baking. A few minutes later, as I lie sprawling in my room in my ‘traditional’ hotel, I realise what the ‘chimneys’ are. They are badgirs — wind-catchers, which trap and funnel the faintest hint of breeze outside and bring it indoors. In more intricate systems, the breeze from the badgir blows over the cool water brought into houses by the qanats. The result? Even without the AC on, my room is at least 15-20°C cooler than the outside temperature. It is not just bearable, it is actually pleasant.

In the evening, I go to the Zur-Khane (house of strength), a traditional Iranian gymnasium. We’re in a vast circular room under a soaring, egg-shaped dome. There is a large pit occupying the centre of the room and, under the pit, another vast subterranean dome over a large reservoir of water being fed by qanats. It’s in the pit that the action happens. As a young man plays intricate rhythms on the tabal and sings (mostly Hafez again, I am told), men and boys in white T-shirts and intricately embroidered leather and cotton trousers perform a ritualised workout, which includes doing push-ups, whirling like dervishes and juggling heavy Indian clubs (what we know as mudgal) as if they were feather-weight. It is a strange meeting of physical fitness regimen and Sufi zikr rituals, the tempo of the exercise varying with the cadence of the music and punctuated by cries of “Ya Ali!” It is entrancing to watch and push-ups to poetry surely beats jogging with an iPod.

I go to see the Yazd atesh-kadeh, the Zoroastrian fire-temple and see, burning beyond a plate-glass window, a flame said to have been burning continuously for centuries. I’ve never been allowed into a fire-temple in India, so it is ironic to be allowed into one here, along with Muslim Iranians, especially since the atesh-kadeh here was built with Bombay Parsi money in the 1930s. On the edge of town, high on a hill, stands an abandoned tower of silence. From the top of a circular stone ruin sitting high on a hill, I look at the amazing views on all sides: the Zoroastrian graveyard, the crumbling ruins at the edge of the city, and the desert and mountains fanning out as far as the eye can see. An appropriately lonely, windswept place for a last journey.

The next day I journey out into the desert as part of a ‘desert tour’. Our mid-point in the journey is Chak-Chak, a Zoroastrian sacred site built around a spring deep in the wilderness. The road to Chak-Chak runs straight through miles and miles of barren emptiness, bounded by mountains on the horizon. Not a bird or animal or human being in sight; just dust-devils and the occasional truck passing by at high speed in the opposite direction. This truly is the Dasht-e Tanhai, the desert of loneliness, and it takes being in Iran to understand the true melancholy of Faiz’s poem. At Chak-Chak, a fire temple is built around the slow drip of the sacred spring, emerging from where the daughter of the last Sassanian king is said to have vanished into the rock when pursued by Arab armies. Here I meet an old Parsi man from Bombay, a retired priest who married an Iranian and has been living in Kerman for 35 years, but introduces himself to me as being from Flora Fountain. He takes me out of the doors of the fire-temple so that he can recite dirty poetry to me in English, Urdu and Gujarati. It’s pretty good, which is to say, it’s all pretty gross. In all three languages.

It is only appropriate, after all this poetry, to pay homage to Hafez’s tomb in Shiraz. The grave is set in the middle of a large garden that is packed and buzzing with people in a way I haven’t seen since the Tehran bazaar. Nearly seven centuries after his time, people are still coming to Hafez. They call him the Lisan al-Ghaib, the voice of the unseen, and Hafez’s Divan, his collected works as it were, gets a status equal to the Quran in all Iranian households. Here in Shiraz, people come to pose by his grave, to pray at his grave, to meditate and to understand the future. They say that if you pray here and open the Divan at random, the ghazal you land on holds the key to your future. Around me, I see many men and women touching their copies of the Divan to the grave, opening it and then getting into a huddle with friends and family to interpret what the verses say. I hurry to the bookshop to buy my own bilingual English edition. The first sh’er my finger lands on —

“Shakkar shakan shunad hamah tutiyan-e hind

Zin qunad parsi ke ba bangaleh miravad”

“How happy in their sugar-pecking these Indian parrots all

Who banquet on this Persian candy transmitted to Bengal”

I start laughing. What else can I do? For, from six centuries away, Hafez is having a laugh at my expense. I am the Indian parrot, revelling in my newfound Farsi. I am also a fan of Amir Khusrau Dehalvi, the Tuti-e Hind, the other poet of Farsi whose grave I spend much time at and whose work and reputation Hafez surely knew (Hafez was born in 1326, shortly after Khusrau’s death in 1325). The icing on the cake is the Bengal reference, because in the middle of my Iran trip, I have changed my departure dates so that I can get back earlier to get to Calcutta in time for a family function. I laugh and then I sit wonderingly, quietly on the steps of Hafez’s tomb, as people come and go, as their futures cloud and clarify, as the sun sets and the sky changes to a deep, star-lit blue.

As I head out of the gates, I stop where the young men offer the divination of Hafez through birds. Here, tiny birds pull out chits with a sh’er of Hafez written on them. But despite all the handler’s cajoling, the bird refuses to pull a chit for me and flies out of his hand and comes and perches on the strap of my bag. I reach out my hand with trepidation to touch the bird, but she is fearless and I gently stroke her till the handler takes her back. Tota maina ki kahani, I think to myself. Not yet old in Iran.

The information

Top tips

Indian travellers get a two-week visa on arrival at Imam Khomeini Airport, Tehran. You need a letter of sponsorship from an Iranian friend or a hotel reservation. That’s all.

Women travellers in Iran need to conform to the ‘modest dress’ rules of the Islamic Republic. Fortunately, this is not quite Saudi Arabia, not even close, and desi salwar kameez with a dupatta (draped over the head) is quite acceptable. One of the most pleasant surprises of being in Iran is just how many women you see in public life, far more so than in most parts of India.

Getting there

Mahan Air (Rs 20,000 return on economy class; 011-43368750; www.mahan.aero) has direct flights from Delhi to Imam Khomeini Airport, Tehran three times a week. Mahan also flies out of Amritsar. Kuwait Airways, Emirates, Gulf Air, Qatar Airways, Indian Airlines and many others also fly to Tehran, but none of these are direct flights (fares on all of these start from about Rs 25,000).

Getting around

Tehran is huge and sprawling, but has a metro. A single ride on the metro costs Rial 2,500 Rial (Re 1=Rial 213 approx.). Taxis can be hired either dar-baste (doors closed, which is to say privately) or shared. Shared works out cheaper if your destination is close to a main avenue. Taxis are relatively expensive in Tehran, but are much cheaper in other Iranian cities (and certainly cheaper than Delhi!). In Isfahan, the bus network is also very good, and a single trip costs only Rial 250 (that’s just over a rupee, folks). Buses are the best way to travel between cities. The roads are fantastic and the buses are air conditioned, comfortable and not very expensive at all. The ‘Volvo’ from Tehran to Isfahan takes only four hours to cover the approximately 350km between the two cities and costs Rial 1, 20,000 (inclusive of snacks and drinks).

Where to stay

Tehran: In Tehran I stayed with friends and spent one night in a budget hotel, the Hotel Firouzeh (from $25, including breakfast; www.firouzehhotel.com) in central Tehran. If you are on a truly shoestring budget, though, Iranshahr Hotel (prices start at less than a dollar; www.hotel-iranshahr.com) might be worth checking out. Budget hotels in Iran, however, deliver as well as mid-range hotels in India. The rooms and sheets are clean, and the rooms often come with TV, fridge and shower. Toilets are shared, however.

Central Tehran: It is the most convenient location to explore the city from, close to all the subway lines, museums and markets. A good mid-range option in central Tehran is the Ferdossi Grand (from $65, www.ferdowsihotel.com). Atlas Hotel (from $50; www.atlas-hotel.com) is another reasonable option.

Hotel: (from $240; www.melal.com), where you can rent two- or three-bedroom apartments, complete with kitchen utensils and modcons.

Isfahan: I was staying with friends again, but Dibai House (from $45, with breakfast; www.dibaihouse.com), in the middle of the lovely, arcaded Bazar-e Bozorg, the heart of old Isfahan, is a good stay option. The Esfahan Traditional Hotel (from $40; www.isfahanhotel.com), in the same area, is a rather lovely-to-look-at mid-range hotel.

One of the nicest ‘traditional’ hotels in a city filled with traditional hotels built in old mansions or newly built in the local vernacular. Silk Road is listed as a budget hotel, but the rooms, atmosphere, food and relaxed setting easily push it up into comfortable mid-range. You can spend hours drinking tea in the courtyard and talking to other travellers and locals, who also frequent the courtyard restaurant for food. A more expensive but lovely option is the Yazd Traditional Hotel (from $65; book through Iran Hotel Info, traditional.yzd@iranhotelinfo.com), one of the newer traditionals in the old city.

Shiraz I stayed in the Niayesh Boutique Hotel (from $30; www.niayeshhotels.com), which is another traditional hotel built around a beautiful furnished courtyard, with a fountain playing in the centre. It’s close to the Shah-e Chiragh dargah and to the main bazaar, while being located in a quiet side alley, away from traffic. Perfect. It also has dormitories and single rooms. More upmarket is the large Homa Hotel (from $180; www.homahotels.com), part of an Iranian hotels chain and recommended by several travellers online.

What to see & do

This list is going to be exhausting, without even coming close to being exhaustive.

Tehran: This is a city of parks and museums. The Park-e Millet in north Tehran is a lovely expanse of green, covered with trees, with the snow-capped Elborz mountains seeming to be just touching distance away. There’s even a cinema hall in the park, where you could catch the latest Iranian film, or just hang out in the cinema’s really impressive bookshop — impressive, that is, if you want to buy Woody Allen scripts in Farsi. But there’s also a great selection of traditional and experimental Iranian music and movie soundtracks. Further down Valiasr Avenue (North Tehran’s main drag and a really pleasant walk, what with the chinar trees and cascading water), there is the Museum of Iranian Cinema (entry fee Rial 20,000), which is a really wonderful place, set inside an extravagant mansion. The museum shop also sells boxed sets of Iranian movies and the works of major directors. Or you could go to the Jewellery Musuem (entry fee Rial 30,000) in central Tehran, in the basement of the Bank-e Melli headquarters, and gaze at the ridiculous amount of jewellery collected by Iranian rulers, including the Darya-i Noor taken from the Mughals by Nadir Shah, and a globe made from rubies and emeralds. The National Musuem (entry fee Rial 5,000) in Tehran is also really impressive and has beautiful artefacts ranging from the pre-historic to the Sassanian.

Isfahan: One can spend an entire day, or days, just hanging around in the Naqsh-e Jahan (Image of the World) square in the centre of the city. It’s a huge, massive public square and all of Isfahan’s grandest buildings are gathered around it. The Masjid Imam, The Masjid Lotfollah, the Ali Qapu palace, and the incredible frescoes of the Qayseriyeh Gate, leading to the arcaded Bazar-i Bozorg. The shops around the square are also a great place — perhaps the best in Iran — to buy handicrafts, including carpets, tiles, and painted metal and lacquerware. Many of them are owned by artisans and you can see them at work. Isfahan is also famous for its nougat and pistachio gaz, and you can buy that here as well. After a hard day of sightseeing and shopping around the square, drop in at the Qayseriyeh tea shop in the evening for a view over the square as the sun sets and Isfahanis come out in droves to stroll and picnic.

And then there’s the bridges over the Zayandeh. The Pul-e Khaju is unmissable, but the Si-o-Seh Pul, further to the west, is no pushover either. There’s a teahouse on the north end of the bridge here and, by walking over the Si-o-Seh bridge from Isfahan, you enter Jolfa, the old Armenian quarter. Here, you can visit the Vank Cathedral (Kalisa-e Vank), the centre of the Armenian church in Isfahan, built in the early 17th century, its interior covered with incredibly detailed and florid paintings. It’s interesting to see the mix of Persian and Armenian, Muslim and Christian sensibilities in the design and decoration of the Church. The museum here also has disturbing reminders of the Armenian Genocide.

Yazd: There is exquisite architecture (the Jama Masjid, Amir Chakmaq complex), incredible performances (at the Zur-Khane, off Amir Chakmaq square), wonderful museums (Water Museum, also off Amir Chakmaq square) and Zoroastrian fire-temples and towers of silence. But my favourite thing to do in Yazd is, um, getting lost.

I just walked around the winding streets and covered bazaars of the old-city for hours. It’s surprisingly quiet and, walking through the streets, the play of light and shadow, shapes and texture and bizarre contrasts piled together is quite magical, and made me itch to take photos like I haven’t itched in a while. The Silk Road Hotel also organises a quite amazing daylong Desert Tour for Rial 150,000 which takes you to 17th century sarais, ice-houses and pigeon towers (Meybod), a Zoroastrian sacred spot (Chak-Chak) and the tumble-down ruins of a picturesque abandoned village (Kharanaq). Do it.

Shiraz: This serves as a good base for exploring the ruins of Persepolis and the tombs and sculptural reliefs at Naqsh-e Rustam. A half-day taxi from Shiraz, which will take you to both, should cost about Rial 400,000. But there’s much to see in Shiraz as well. The most obvious attraction being Hafez’s tomb, the Aramgah-e Hafez. The citadel at the centre of the city, the Arg-e Karim Khan; the ornate main market Bazar-e Vakil; and the Shah-e Chiragh shrine all merit a visit.

Where to eat

Tehran: The Khayyam Traditional Restaurant (+98-21-55800760), set in a 300-year-old building, is pretty superlative. It’s close to the Khayyam Metro Station and just outside the Tehran Bazaar. The dizi (meat and chickpea stew) is pretty awesome. Tehran also has a great pizza chain called Avachi (21-88531345), which makes quite decent all-vegetarian pizzas.

Isfahan: The courtyard restaurant of the Hotel Abbasi serves a kickass osh-i reshte (thick lentil and vermicelli soup). Many places in Isfahan serve rosewater ice cream, and the Qayseriyeh Teashop (up a flight of stairs next to the Qayseriyeh gate) is great for some relaxing tea and sweets and a smoke of qalyan (hookah).

Yazd: The Silk Road Hotel serves a mean camel stew, as well as osh-e ju, a healthy chicken and barley soup. Nemoner Sandwich (no phone, but it’s easy to find) on Imam Khomeini Street also serves a pretty awesome camel burger. The advantages of being on the edge of the desert.

Shiraz: The Sharzeh Traditional Restaurant (71-2241963) is the place to have dinner. Good kebabs, fresh bread and babaganoush starters, and a band performing traditional music.