Some people just have a bee in their bonnet. Mine had, for years, been buzzing at me to travel that fantastic piece of living history, the Grand Trunk Road. I couldn’t settle for admiring the superlatives—thirty-five centuries old, 2,400km long, the 17th-century ‘Long Walk’, Kipling’s “river of life… the backbone of Hind”; and it didn’t count to be chauffered—I had to personally haul myself over the entire thing. Like Sher Shah Suri, like Kim of the eponymous novel. Like my father 36 years ago, when he couldn’t afford to ship his car.

Finally my day had come. I had a Ford Ikon from Hertz and a mandate from the office to drive all 1,846 kilometres of the GT Road in India, from Kolkata to the Wagah border. Milan would be my co-driver and take pictures. The plan: 1. Start on Monday. 2. See how it goes.

The vehicle was delivered to the Fairlawn hotel at 10am, white and sparkling; we set the odometer to zero; pushed Simon & Garfunkel into the tapedeck, and set off. The Kona Expressway took us out of Kolkata. There, in the distance, was a long perpendicular purple streak overhung with a faint roar. My heart leapt. We turned left onto the greatest, Grandest, Trunkest Road in the world and pointed the nose at the Pakistan border.

We’d opted to travel west, rather than in the traditional eastern direction of traders and marauders, to keep the sun out of our eyes. It shone benignly on a properly Olde Worlde sign reading ‘Straight Way To Delhi’. We were on the shady dual carriageway of NH2, known here as the Durgapur Expressway. Suddenly it became a bare, bumper-to-bumper stretch at a yellow board that said “Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee’s Dream Project of Golden Quadrilateral. 4-laning of Palsit-Dankuni Section”. The PM was pointing dreamily into the distance. The 4-laning process, itself highly un-dreamy, is due for completion on this section late this year or early the next. The PM would accompany us all the way.

In the meantime we inched past vast beaches of sand and gravel, past massive yellow machines designed to flatten and straighten road, past stands of truck accessories—tinsel and tassels for the front and sides, old shoes and fierce faces to hang on the back. I drummed my fingers and craned my neck, itching to cover ground. Truckers, who often cover it thrice a fortnight, quietly turned off their engines and snoozed. Three hours later we pulled over for lunch. We’d covered 72km. If we kept up this blistering average of 24kmph, we wouldn’t be in Dhanbad, Jharkhand, before 11pm.

West Bengal drifted by, treeless and dusty. Buildings have been cut cleanly back for road-widening, so that cross-sections of living rooms and shops hang in limbo, indecently exposed. Something called ‘Liquid Nitrogen Plant & Frozen Semen Bank’ had survived. Kids played cricket on the rough construction. By five o’clock we’d been through four music tapes and were stuck in a twilight zone, less a settlement than a slight thickening of chaos. Horns blew, triple lanes emerged, opposing traffic got stuck, dust rose in columns.

Then God took pity and, 17km short of Durgapur, delivered us through a toll gate unto a fantastic highway, a bit of the PM’s Dream Project come true. Out of the darkness shone a white stripe on a perfect tarmac edged with properly reflective strips. It was clean enough to eat off. I regarded this as a divine reward for getting through the first 163km of the day, which had taken six hours to cover. The next 100-odd km flew by in just over one creamy hour. If this is what the PM is dreaming up, I say keep him sleepy.

At the turn-off to Dhanbad at 7pm, Sanjay Srivastava was waiting to escort us to the Central Industrial Security Force guesthouse where he’d kindly fixed for us to stay. Sanjay is Reliance’s man in Dhanbad, where everybody else flatly refuses to go. Over dinner he regaled us, if that’s the word, with stories about the various mafias in the city. Like when a mobster walked into his office and growled that lousy service had almost got him killed when his mobile went dead as he was being chased by a mortal enemy. Customer Care—Dhanbad-style. Sanjay’s advice was to barrel through both Jharkhand and Bihar straight into Varanasi, a drive of 430km. “Beyond Dhanbad,” he said, “roll up your windows, lock your doors, and if anyone approaches you, run them over.” He was perfectly serious.

We set out before sunrise, tanked up, and enjoyed more brilliant highway. Low rusty hills on the right, blue sky and beautiful golden light: Jharkhand was picture-pretty. It was hard to believe that this is lawless territory in which the dreaded Maoist Communist Centre holds sway between Dhanbad and Gaya. It’s too bad that they get the wildest and prettiest bits. Roadsides stalls sold spears, lances and knives of a deadly beauty, and carved and painted bamboo lathis. Off the road, on a hilltop, was the Parasnath temple, but we weren’t Jain pilgrims and we had a gruelling schedule.

The morning passed in ploughing through towns like Barakata, Barhi and Champaran. At each of these NH2, otherwise a perfectly good motorway, turned into a heap of rubble, as if the residents had taken a wrecking ball to it for some unspeakable offense. Past Champaran it just gave up and sank into a state of potholed gloom; we crossed into Bihar among dusty trees that looked like judges in powdered wigs, past signs like “Better be Mr Late than late Mr” and some very pretty countryside. Empty countryside. All the Biharis are possibly working on construction sites in Delhi. We stopped once, briefly, for a dhaba lunch. All through Bihar, large signs advertised Amul Janghiyas/Panties (“Jo andar fit, voh bahar bhi hit”); and NH2 remained under construction beside boards like: “Central Government Road Fund Project. Rs 2,179,900,000 sanctioned Feb 2001. Length 40km”.

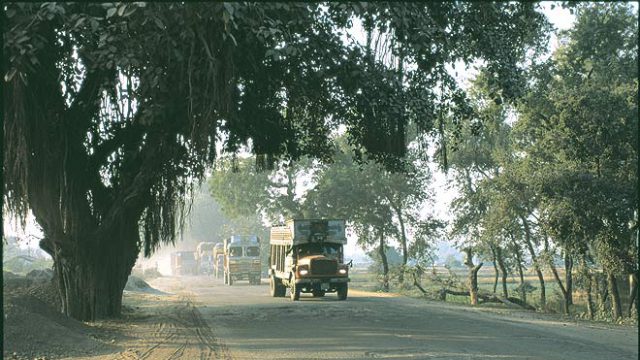

After Dehri-on-Sone, the GT became the gentle, tree-lined road it must have been back when travel was slower, amid elephants, horses and genteel palanquins. That seemed appropriate near Sasaram, where we stopped to pay homage to the Lion King, Sher Shah Suri (1472-1545), who made it all happen: turned an ancient footpath used by shepherds and traders into one of the greatest travel and communications arteries in the world. He planted trees to create a sun-proof canopy, and built caravanserais to rest in. His road ran from Sonargaon, now in Bangladesh, to Peshawar.

The sun set becomingly over his tomb, and reflected off the moat around it. It’s deeply sobering to ponder the sort of self-esteem that allows a man to plan his own grave on such a grand scale. It is magnificent yet solemn, a powerhouse as well as a crypt. This, proclaims every stone, is the resting place of a very great Emperor.

It was 5pm, and we still had 100km to go. Very soon Varanasi became a shining Shangri-La as we struggled through some of the worst motoring terrain I have ever seen. Thick dust refracted light into blinding spears, so that I was often driving purely on intuition. The last 40km of Bihar were, quite simply, a nightmare. Finally, after a long hungry wait in line, we crossed into Uttar Pradesh at 7.30, and two hours later turned off into Varanasi. The Ganga View Hotel was clean, comfortable—even a bit fancy. We needed fancy. We’d been driving for 15 hours. Everything below my bottom was numb, everything above was humming fiercely. No way was I rising at 6.30 to drive again; we called a rest day. After a hot shower and dinner we crashed, and slept like the dead.

The next day passed in a blur as we pottered around trying to stop making reflexive brake-pressing motions. We took a cycle rickshaw to the Bharat Kala Bhavan museum, and a boat ride to Dashaswamedha Ghat for the arti. The cycle rickshaw man guilt-tripped me into visiting the Kashi Vishwanath temple, amid tiny lanes where sky comes in strips and patches. “Benaras is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend and looks twice as old as all of them put together” said Mark Twain, and right he was.

Uttar Pradesh briefly impressed with good road, though for the first time in 700-odd kilometres it bore pedestrians, wobbly cyclists, and animals. But there were lissome eucalypti, and if the unrepaired had large holes, the repaired bits were nice. I was fascinated by what is happening to the Grand Trunk Road. On one hand, road-widening is a boon for travellers. On the other, the magnificent 400-year-old banyans and pipals planted by Sher Shah Suri have disappeared from West Bengal to Uttar Pradesh. I hope they have a very good technical reason for why they can’t be preserved in a road divider.

We shot through Barot, Hadiya and Hanumangarh. They haven’t gotten around to building the Allahabad bypass, which enabled us to taste some fine Allahabadi guavas. Between Allahabad and Kanpur the road alternated between fabulous and hideous. On it travelled fewer trucks and more tempos, cyclists, ikkas, tongas, pedestrians and the odd pig. At 7.30pm we were ensconced in The Attic, a charming little guesthouse in Kanpur—itself just a dusty commercial centre.

The next morning was sparkling clean; we took off early, asking our way out of Kanpur to Agra. Amazingly enough, we were racing along a two-laner shaded with enormous trees with shining leaves. There was no construction. Who needed construction along this lovely road? Who needed a map? It was only 80km later, beyond Kannauj (where, by the way, Sher Shah clobbered Humayun), that I noticed that the yellow-topped milestone read NH99. Groan. I considered backtracking and leaving Kanpur again correctly, but time was ticking. We put ourselves back on the GT at Auraiya, via a side road. Lost on the Straight Way to Delhi—that takes talent. We’d added three hours’ drive time to the day, and now I’d never know what the 100km between Kanpur and Auraiya looks like.

To rise to the challenge of actually traversing the damn thing, it helps to keep in mind the greatness of the GT Road—and great it is. Imagine the Aryans of 3,500 years ago, sweeping over the plains from the Northwest, wearing a faint path with their feet. Imagine that path being tramped into an ever-wider dirt track over the centuries, by elephants and horses, armies and carriage wheels. Imagine the great religions growing or spreading along it—Sikhism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Islam. Think of farsighted Sher Shah, restoring and beautifying it in the 16th century, making it a 2,400-km, traveller-friendly artery linking his empire from Bengal to Peshawar. Of European maps of India that showed it complete with trees. Of the British, paving it in the 19th century and giving it its name—the trunk that connected all the branch roads; and of the millions of people it bore in both directions during Partition. And think of Vajpayee taking this old, old thing into the 21st century as part of the mind-bogglingly vast Golden Quadrilateral project. Now that’s amazing.

All this thinking and imagining came in handy. Because of all our driving on the GT, including 15 hours through Bihar, nothing was as bad as the last lap to Agra. The road was just a bomb site of pebbles strung between large, deep holes. As the light faded we lost more and more speed because of chassis-eating craters. A surreal roadside sign in the middle of nowhere read ‘No Parking’. My back was killing me, my knees were breaking from clutch use, my eyes agonised by oncoming brights. I collapsed in the passenger seat with an almighty headache an hour and a half before we drove into Agra at 8pm. We turned off the GT and into the first hotel we hit, which was on the third floor of a commercial building and had cardboard walls and fabulous omelettes.

Agra to Delhi: 200km covered in under three hours on a four-laned Golden Quadrilateral stretch so rapid and beautiful that it was mildly boring. My soft spot for Emperor Akbar got softer when I saw the tomb he’d commissioned for himself at Sikandra, 2km out of Agra. Besides the splendid gates and deer-filled gardens (really), the tomb is a sort of architectural sauna: the warmth of a lushly-ornamented foreroom followed by the sobering cold slap of an utterly plain space with simple plaster and an exquisite brass lamp donated by Lord Curzon hanging over the grave. I was impressed by the lamp until the caretaker told me that it was put in to replace the gold one that the British made off with.

Besides the great pleasure of a smooth, speedy drive, we passed several kos minars, medieval milestones, still standing phallic and grand in the mustard fields. Entering Delhi at its Mughal gates felt wonderful. It was probably cheating to go home and spend a day recouping, but I was knackered, and I did, and I’m glad.

The last stretch of the journey, from Delhi to Amritsar on what is now called NH1, was lined with kos minars, extravagantly-sized dhabas (Punjabi-style), and tall eucalyptus shading the margins of the most exquisite asphalt. We hummed along near 100km most of the time; it was a matter of eating up kilometres on world-class highway, barring the traffic through towns. Near Ambala, at Shambhu village, we chanced upon a Mughal caravanserai, a beautiful fortified structure lined with small cells in which travellers once bedded down for the night. We covered the 420km to Amritsar in nine hours, stopping along the way, but if you leave Delhi early it can take as few as six.

Amritsar proved a pleasant little town. After a night at the Tourist Rest House we wandered the Old City, lingered in the Golden Temple and Jallianwallah Bagh, and in the afternoon set off for the last gasp.

And a smooth 36km later, beyond Attari village, there it was—the last milestone of the Grand Trunk Road in India: ‘Wagah Border 0km’.

Being a sucker for military pomp and ceremony, I had always wanted to attend the nightly flag-lowering. I was entirely unprepared for the jolly little circus that it turned out to be. We were coralled into neat rows and herded into bleachers. The ceremony got underway with much soldierly yelling, goose-stepping and playing to the galleries, loud music on either side attempting to drown out the other, and screaming, cheering audiences. Are there always so many people? I asked the officer on crowd duty. “Always,” he said wearily, “and more on Sundays.” Understandably. If I lived in Amritsar, I’d turn up at least twice a week.

It was the perfect cap to my journey on the Grand Trunk Road. It was thrilling to know that the road carried on; and equally thrilling that the state of Indo-Pak relations meant I could call it a day. It was time to take the Amritsar Shatabdi back to Delhi. I was still vibrating from top to toe, and I would forevermore associate Cat Stevens with Jharkhand but, finally, I could rest easy.