The train has disgorged me along with a thousand others. Puri station today has that special character of a place where rural India has arrived on pilgrimage. A quiet focus in the face of hardship; a stillness that can rip into a surge on a dime. They’ve come to see Jagannath, the god who gets off his throne and out on the street once a year so his devotees can get up close and personal. This year is special because Jagannath is getting a new body after 19 years. They’ve come in millions from all over the country with the inexorable force of a natural phenomenon. Not unlike the annual “arribada” of the Olive Ridley turtles at a beach near here. I feel like a hermit crab, stung by the sense of purpose around me. In this sea of dhotis and pagris, of rudraksh and tulsi beads, of leathery faces and gnarled fingers, I am a bit of deracinated flotsam. I am not a believer. I’ve come to watch the believers believe.

The scene on the platform is India on a plate. I pick my way past a group from Kanchipuram in crisp veshtis and angavastrams. Right next to them is a large family whose matriarch has just poured out choora mix on a newspaper and everyone is scooping it up with their rotis. Where are they from? Dewas district, MP. I hear various tongues as I walk past groups from Chhattisgarh, Telangana, Jharkhand. A one-legged man walks with a crutch, tucked in it are his toothbrush and a dried bunch of roses. An ancient sadhu, tall and gaunt, eagle eyes focussed ahead, carefully makes his way with the help of his cane. Riding the crowd out of the station onto Chakra-tirtha Road, I walk abreast a group of wiry sadhus in dreadlocks from Ayodhya. They worry for me, a lone woman in this Rathayatra melee.

I go to the Chakratirtha beach at sundown to find the breaker line studded with fully dressed men and women submitting to the waves with unbridled glee. In many eyes, old and young, I see that special glow of seeing the ocean for the first time. I am yanked back to my nine-year-old self and my own first time right here at Chakratirtha. As the sun sets, the sand takes on a pillowy look in the gloaming. Sitting on it near me is a clot of men, some with coloured pagris and one with a glorious silver mane. Parked on a pile of amorphous bags next to them is a sublime ektara: smooth and red of body, with a hand-painted border. As if on cue, silver-mane picks it up and starts to sing, his high nasal voice anchored by the solemn drone of his instrument.

Tomorrow is the big day. The temple itself is closed until morning when the deities will emerge to board their chariots. As I walk up the wide expanse of Grand Road that evening, the towering spire of the Jagannath temple comes into view, with its red standard rippling in the breeze. The three chariots are parked near the south gate of the temple, each about 40 feet tall. Craftsmen are feverishly putting last-minute finishing touches: brass ornaments are being fixed onto massive appliqué Pipli drapes, the minor gods and charioteers are getting their moustaches painted, enormous coils of coir rope have been stacked. The place teems with visitors and police. The air is electric with anticipation.

On the morning of Rath, I visit Koili Baikuntha, a secluded garden just inside the north gate of the temple. “This is where it all begins and ends,” the garden’s attendant says of his workplace. He shows me the four carts on which the neem logs for the fresh deities had arrived, the four stone discs atop which the deities were carved—one each for Jagannath, his brother Balabhadra, his sister Subhadra, and his chief weapon, the Sudarshan. He points to the thatched pavilion where Puri’s king had performed a special fire sacrifice. Then he brings me to a muddy pit and says in a hush, “This is where the dead gods are buried.”

The oval pit is about 3 feet deep and 25 feet across, with fresh mud at its bottom shrouded by the shade of surrounding trees. A lone woman sits hunched at the edge of the pit, next to a squat temple to Shamshan Kali. It’s morning but it could’ve been night; her white sari stands out in the shady gloom. She lights a ghee lamp. The light catches the wrinkles crisscrossing her face. I see that her sunken cheeks are wet. She sets the lamp down and dissolves in sobs.

Just a few feet away is a world apart. The hush in Koili Baikuntha is a distant memory as I get sucked into a maelstrom in the temple courtyard. A mammoth crowd, all agog, has gathered outside the doors of the inner sanctum. Raucous cries of “Joy Jogonnatho!” rent the air. Jagannath is about to emerge in his new body—Nabakalebara—and will be carried out to his chariot in a ritual called Pahandi.

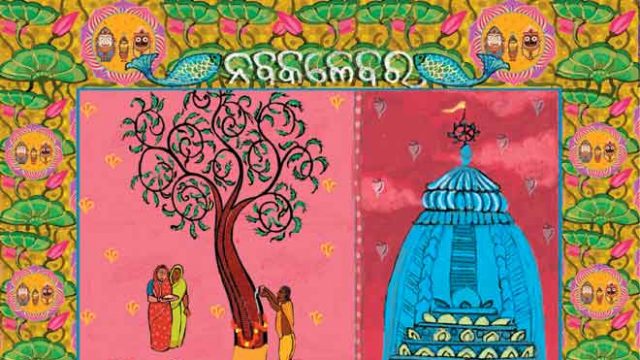

Jagannath is the only major Hindu deity with a renewable body. No stone or metal splendour here, no flights of sculptural fancy. This god is fashioned from neem wood and periodically discards his old body for a new one through a raft of elaborate rituals spanning months that culminate in his fresh appearance at Rath. 2015 happens to be such a Nabakalebara year; the last one was in 1996.

Scholars have long noticed that Jagannath resembles no Hindu icon and that his cult coincides with the worship of renewable wooden posts prevalent amongst the Munda, Kond, and Sabara tribals of this region. Some say that Jagannath arose from Jagant, a tribal deity of the Sabaras of Koraput, in south Odisha. Whatever the origins, the ritual practices in the Puri temple remain decidedly unusual. Caste is not an issue in the priesthood and Brahmins are certainly not on top. It is the Sabara tribals who have a special place. Sabara priests, called Dayitapatis, claim Jagannath as their brother and have exclusive rights to serve him and his siblings during the run-up to Rath each year.

On Nabakalebara years, the long series of renewal rituals are also performed exclusively by them. It is they who track down the neem trees bearing special signs, ritually sanctify them, cut them down and bring them to Koili Baikuntha. And once the new deities are complete, in the dead of night on an auspicious date, the Dayitapatis perform the mysterious act of transferring the ‘souls’ of the old deities into the new and bury the dead deities in that muddy pit in Koili Baikuntha. This is followed by a month of fattening up the deities with silk yarns, followed by perfumed oil, and lastly paint. The final act of painting the eyes is the only one reserved for Brahmins and happens the day before Rath. By then, Jagannath has been out of sight for over six weeks and his devotees are feverish.

Standing in the temple courtyard waiting for the Pahandi to emerge, this pulsating fever of the devotees around me was having an effect. I now wanted to get inside the inner sanctum. I had fallen in with a well-connected family who had taken me under their wing. They asked me hang close to them and watch for signs. Things happened in a flash. A bouncer-like Dayitapati appeared at a small side door and there was a surge towards him. He beat back most of the crowd, but not the family I was with. I felt crushing pressure, someone elbowed my ribs. A large mass passed through a narrow opening, like natural birth. And suddenly, I was in.

The scene within was an operatic dystopia. The fifty or so people inside, exuding vapours of power and wealth, displayed a manic desperation to get to Jagannath. They pushed, trampled, clawed—as if reaching for their first meal after a long starvation. The police officers pushed back; one SP had an all-out fistfight with a man who I later learnt was a sitting MLA. I saw money changing hands to subdue the cops. This violence played out within a few feet of the deities. Juxtaposed with this was the tearful ecstasy of those who were viciously jostling a moment ago, but had now touched their god in his new body.

And what of the god himself? Those enormous cartoon eyes and the permanent smile, those stumps for arms and no feet. His massive flat head bound in a red gamcha, he looked helpless. Plastered against a cool stone wall, I watched devotees swarm him like worms. They tore at him, caressed him, clung to him. The white of his eyes was getting smeared by the black from his face; the black on his pug nose was fast fading to the pale neem wood beneath. Jagannath, the master of the universe, besieged. I felt a stab of affection for him. I wanted to protect the protector. I wanted to pick him up and run. Instead I joined the swarming bodies and stroked his discoloured nose. He felt warm to the touch. Maybe it was the collective body heat. Or maybe he was feverish.

Making my way out of the temple, I’ve lost my slippers. I’m now barefoot on the hot asphalt of Grand Road, like a proper pilgrim. A collective roar goes up at noon as the Pahandi emerges and Jagannath is installed on his chariot, the last of the three siblings. All of Grand Road—300ft wide, 3km long—is a sea of heads. The crowd waits in the blistering sun. The king of Puri, Gajapati Maharaj Dibyasingha Deb, arrives around 3pm for the ceremonial sweeping of the chariots. As he leaves, the police brightly decide to lathi-charge out a path for him through the solid crowd. I am caught in the ensuing mini-stampede and get miraculously spat out at the edge of the path, face to face with the king, who looks visibly embarrassed.

At this point I’ve had enough of the mosh pit and retreat to a roof overlooking Grand Road. The scene below me is straight out of a British Pathé clip of the 1928 Rath, except for all the plastic now and the elephants then. Balabhadra’s chariot starts to move, bringing the word juggernaut to life. The police fail to predict its speed and can’t clear the road fast enough, leading to another stampede. I see bodies sway and weave like reeds in a storm. Some pass out and are trampled. It occurs to me that this raging mobile tableau is, in fact, a part of the still immutable centre of India. This is how it has always been, and will be. By 6pm, Subhadra and Jagannath’s chariots have stopped midway for the night. Sobbing devotees are ecstatic to have their god out amidst them for the entire night. Rath will continue in the morning.

As I walk to the station at dawn, pilgrims are still arriving. A group of elderly women approach me and their leader asks: “E babua, samundara kidhar ba? Naha leva.” Her question leads to an epiphany. This is how rural India travels, on the wings of an easy ownership over India’s pilgrimage geography. She wants to bathe in the ocean, but is she going to travel just to go to the beach? No, that’d be unimaginably self-indulgent. She’s going to fight a packed train and enormous hardships to come to Puri for Jagannath, for Rath, for Nabakalebara, and get the ocean as a bonus. Her ownership of Jagannath extends to Puri’s ocean and makes it hers in a way that it’ll never be mine.