The plastic junk that swamps the Ganga around the Howrah Bridge is replaced here by marigold and hibiscus tidbits. What if they are the desiccated remains of a reverent offering? As flotsam, I would readily accept the hibiscus whirling in the waters near Belur Math, where the ship is anchored mid-stream. Who wouldn’t?

“Welcome aboard,” says Atul Bhatt, general manager of Pandaw Cruises India Pvt Ltd, and I turn away from the sight of the Hooghly’s khaki tide gobbling up the marigold and hibiscus. A uniformed attendant supplies us with neatly folded wet fragrant towels; another collects them, now crumpled and carrying the soot of a sweltering city. Yet another liveried staff member ushers us to our twin-bed cabin — a cocoon of cool air-conditioned comfort, tastefully readied for use and bounded on all sides by elegantly weathered Burma teak. The Bengal Pandaw soon starts moving.

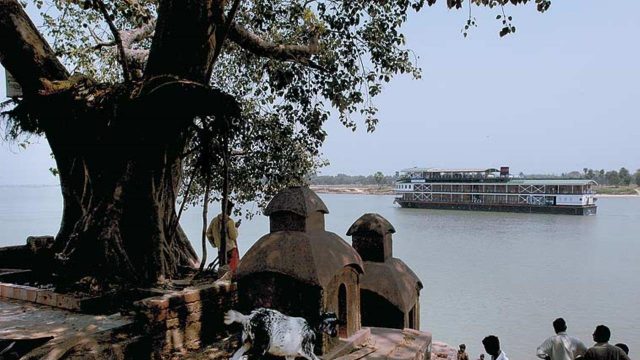

It is an old journey that Pandaw has now revived. The Kolkata-Varanasi riverine route on the Ganga was, at an earlier age, a busy route for trade, commerce and ambition. The river was wide enough and deep enough to allow the bulkiest ships from Europe to reach as far as Patna; it was accessible enough for the Portuguese, the Danes, the Dutch, the French and the British to set up colonial camps along the river’s lucrative shores in Bengal; and it was viable enough for trade in everything from indigo to opium and for great civilisations to flourish along its banks.

As we meander along the silt-heavy waters of the Hooghly, the Bengal Pandaw seems like a lonesome voyager attempting to uncover the Hooghly’s hectic history.

Incidentally, this journey was initially part of the Pandaw Cruises international itinerary. While the larger concern has withdrawn this tour and posted a notice of cancellation on its website (www.pandaw.com), its Indian shareholder — Pandaw Cruises India — is continuing to operate the sector. Since the luxury 14-night, 1,280km cruise from Kolkata to Varanasi began in September last year, the Bengal Pandaw has seen its 28 cabins booked to capacity in its last three trips, with each guest paying $4,000 as passage fee for a journey where everything is taken care of, including lectures from historians and naturalists and yoga-inspired spirituality. For approximately Rs 1,84,000, the Pandaw’s exclusively Western clientele (the cruiseboat operators can’t remember a single Indian guest on its first ten trips) has the privilege of watching a riverine life and style that even Indians are often not privy to.

“What is there in it for guests on the Bengal Pandaw?” I ask Raj Singh, scion of the Bharatpur royal family, with interests in tourism projects in Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary and Kanha National Park among others, a well-known ornithologist and fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, author of books on birds and wildlife, and a director of Pandaw Cruises India.

Right now, he is one of the two people (the other being his Britain-born wife and long-time travel companion, Diane Singh) braving the summer afternoon in the Pandaw’s cheerfully laid-out sun deck. It’s remarkably windy on the deck but the wind does nothing to lighten the heat.

“Great rivers are revered everywhere, but none enjoy the status of the Ganges,” says Singh, taking a break from his reading: Abraham Verghese’s Cutting for Stone. “You see people bathing, rituals taking place, village life, temples and palaces. You go through an ancient culture and civilisation that has held on.”

I walk across the sun deck, past the blue-topped deck chairs and the all-hour bar that is readying for the evening buzz, and stand at the bow of the ship, alongside the master’s cabin. It could have been my own ‘My Heart Will Go On’ moment if not for the heat and, importantly, the lack of intimate company.

What I have are the sights and sounds. As the three-tiered ship ploughs through the water, travelling at no more than 10km/hour, a survey vessel — Meghna, commissioned from the Inland Waterways Authority of India — leads the way through water channels that are deep enough to hold afloat the flat-bottomed Pandaw. Occasionally, Meghna’s siren lets off a shrill hoot, warning small fishing boats about the approaching ship — arguably the largest plying these waters — the sight of which invariably draws loud cheers from children in the villages lining the riverbanks.

As the oars of passing fishing boats flash through the water, the chirping of retiring birds and the strains of kirtan music from a nearby village accompany us for a distance. Near the erstwhile Portuguese settlement of Bandel, the wind brings in a whiff of mortality from the crematorium, while the steps of ancient ghats are lit up by the soft late-afternoon sun.

The ship winds past sprawling Rajbaris, with their mix of Indian and European architecture, which stand as crumbling reminders of a well-heeled bohemian past, where palaces resounded with the performances of nautch girls. We know from Bengali literature that the zamindars used barges to supply their British masters with alcohol and allurements in return for business-related favours. The jute mills by the river mostly remain closed and idle chimneys stand as sentinels over an industrial wasteland. Decadence back then, dazzling decay now.

But the river remains as treacherous as it always was. Throughout the length of the Pandaw’s journey, its unpredictability is a constant threat for the propellers and radar — as also for the journey itself. “The water channels change daily. What is a deep channel today, may become a sandbar when the ship makes the return journey from Varanasi,” explains Mahadeb, the master of the ship, as pilot Lakshmi Chowdhury tries to connect through a wireless set with the survey vessel as a bridge approaches: “Pandaw calling Meghna, Meghna.” Meghna, equipped with Echo Sounders, laptops and maritime experience replies that, since low tide conditions are prevailing, the Pandaw can easily cross the bridge. “The water changes colour thrice daily and often we have to understand depth from such indications,” the master says.

Every night, around the time the Pandaw’s guests retire to their rooms after the buffet dinner at the spacious glass-panelled dining area, 350-odd boatmen, with red and green lights atop their country boats and equipped with only oars, navigate the river between Tribeni and Farakka. Their role is to indicate what the water levels are like on a stretch. They are part of a Night Navigation System that has been in place since 2002 — unsung, even unseen, heroes of the fickle waters.

Being the first such venture (though competition is expected soon, at least between Kolkata-Patna), the Pandaw has to find a way of dealing with immense logistical issues. For instance, because large ships have not been working this route, low-slung pontoon bridges have come up in places like Bihar’s Danapur. These have to be cut and rejoined each time the Pandaw cruise ship passes, says Vishu Singh, a director of the cruise company, while a portion of another Bihar bridge has to be unhinged and later restored. And near the Jangipur Lock Gate in West Bengal, three high-tension electrical wires have to be switched off for five minutes to let the ship pass. The ship consumes 750 litres of diesel to move and to keep the air-conditioning system running through the day.

As I return from my position at the bow and head towards the Salon Bar at the upper deck, where feature and documentary films are screened twice daily and which also houses a mini library besides a selection of Indian and foreign liquor, Raj Singh is fast asleep on the deck chair, Cutting for Stone on his lap. So is Diane on the adjacent chair, lulled to sleep by the untamed river breeze, Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide on her lap.

The trip, of course, get its name — ‘Slowly on the Ganges’ — from Eric Newby’s Slowly Down the Ganges, a chronicle of his 1,200km-long journey down the river sometime in 1963 with his wife Wanda.

A couple of days later, inadequate water levels forced the cruiseboat to turn around. A disappointing turn of events, of course, but we did manage to visit the gorgeous terracotta temple village of Kalna in Bengal. “The average age of the clientele on the Pandaw is above 60 and most people are very well-read and have an understanding of India,” Diane says, as the Pandaw anchors off the former French colony of Chandernagore. “While some have their roots in India, each person finds a reason to be on board.”

The information

Route

After it leaves Kolkata, the ship first stops at the former French colony of Chandernagore, followed by Bandel, one-time Portuguese settlement where the Bandel church and the Hooghly imambara stand close together. The intricately designed terracotta temples at Kalna and brass and copper work at Katwa are the next attractions. At Murshidabad, guests visit heritage structures dating back to the time of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the last independent Bengal Nawab. There are ancient terracotta temples to visit at Baranagar as also the local Farakka market. A mosque dating back to Akbar’s time is the prime draw at Rajmahal once the ship enters Jharkhand, after which a visit to the ruins of the Vikramshila University in Bihar is on the agenda. Yoga school and ancient monuments are the attractions at Munger. Guests are then taken to Barh, from where buses take them to Buddhist pilgrimage spots like Bodh Gaya and Rajgir. In Patna, there’s a tour of the museum and Golghar, a granary built after the Bengal famine of 1770. Dolphins are often visible along this route, and the area around Buxar is particularly noted for wildlife sightings. From there, the ship travels to Varanasi, via Gazipur.

Itinerary and Dates

The sailing season is October-March/April, depending on weather and river conditions. Dates for the first sailing of the coming season are not yet available. During season, the ship sails once each every month from Kolkata and Varanasi (14N/15D). A trip to Mayapur (2N/3D), which will include stopovers at Kalna and Chandernagore, is on the cards. This trip is largely targeted at Indian customers. Though exact dates haven’t been fixed yet, the first sailing is likely to take place in May.

Prices

Kolkata-Varanasi: $8,000 per couple (approximately, depending on individual travel agents). Kolkata-Mayapur: Rs 29,000 for rooms in the lower deck and Rs 35,000 for upper deck.

Contact Pandaw Cruises India Pvt Ltd, 011-26122290, 26122291, reservations@pandaw.in