The Chinese fishing nets, Jewish synagogues, Portuguese churches, Dutch palaces and British village greens appear like punched impressions left by those that settled and invaded Kochi. It should not be surprising that the port absorbed these often-violent incursions into its framework to create a patchwork quilt of cultures when its birth was itself the result of a flood in 1341. A sleepy fishing village was transformed into a natural harbour and Kochi suddenly had new value as a trading post to the royal family and to the Arab, Chinese, Dutch, British and Portuguese spice traders. Though pepper is no longer the black gold it once was, the southern peninsula of Fort Kochi and Mattancherry and the islands of Willingdon, Bolgatty, Gundu and Vypeen still contain one of India’s largest ports and a major naval base.

Any important building in Kochi will tell the history of this ‘Queen of the Arabian Sea’, if you listen. Mattancherry Palace, where the royal family held their coronations, was built in 1555 by the Portuguese and so the tale unfolds in stone of Vasco da Gama’s arrival in 1502. He came in search of a sea route to India and seized Kochi as a lucrative trading post. Later there were ‘negotiations’ where a ‘gift’ of the palace was made to Raja Veera Kerala Varma in exchange for trading rights. The palace is popularly known as the ‘Dutch Palace’ and in the misnomer lays another tale, of the second invaders, the Dutch. Lured by Kochi’s spices and ivory they came in 1602 and, after seizing control in 1663, renovated the palace so that the large white, red-roofed structure came to represent both Dutch and local architectural styles.

Inside, it is now only a museum with musty coronation robes, roped off palanquins and admittedly still sensual murals, like the one of Krishna, his many arms simultaneously at work on eight delighted gopis. For me though, the museums are often the last place I go to see. It’s not where the soul of a place is. I know these things need to be removed from pollution into glass cases so we can see them and learn from history, but when they are removed from their environment they lose their purpose and become only objects. History explained on neat typed museum cards.

For me heritage survives if it can and does reinvent itself. Then it is still part of the fabric of a place — living heritage. The beauty of St Francis Church, believed to be the first European church built in India in the 16th century, is for me its continued use so that what once was can be imagined while you’re in its heart and not at the careful sidelines behind ropes. Sitting under the British ‘punka’ fans, with the clacks of the administrator’s typewriter echoing off the Portuguese and Dutch tombstones embedded in the walls, I wondered how St Francis had lived to tell the tale of all its conversions. Christians can be pretty unkind to other Christians, as Ireland proves, and so its endurance through its transformation from Catholic Portuguese to Protestant Dutch, to British Anglican (they took control in 1795) and now to the Church of South India is extraordinary. There are still services on Sunday and some of the tourists crossed themselves before taking a photograph of the interior, but it was in the 1557 Roman Catholic Santa Cruz Basilica that I felt like an intruder into faith. There wasn’t an office enquiry desk, or the noise of Rev P.J. Jacob checking his mobile phone for messages as at St Francis. In the colourful Indo-Romano-Rococo interior, to the drifting hallelujahs of the Basilica Malayalam Choir practising next door, nuns and the faithful spoke to their God.

There are hardly any Jews left in Kochi to pray at the Pardesi (white Jew) Jewish Synagogue, but I liked the conversational sense of worship with the brass pulpit in the centre, that is until I was told the women had to sit separately up in the gallery. Still the oldest Jewish synagogue in the Commonwealth speaks of the unusual tolerance for the medieval dispossessed children of Israel. The Jews came to Kerala; some say in 587, fleeing from Nebuchadnezzar’s occupation of Jerusalem, others that they came in the 11th century in King Solomon’s trading fleet. Either way they were accepted and settled, trading in spices in Cranganore north of Kochi. When the Portuguese Inquisition arrived in early 1600, carrying out their persecution and burning Jews at the stake in Goa, the Raja of Kochi gave the Kerala Jews a parcel of land near the palace from which the community thrived during the great trading period. That perhaps is closer to the point. Kochi was inclusive because it thrived on trade, and business is business. The Jews were valued as traders, who spoke Malayalam, and they were successful as evidenced in the Belgian and Italian chandeliers that hang from the ceiling of the synagogue and the delicate willow-pattern floor tiles, each hand-painted and brought from Canton in 1776.

After the British left, the Jews were offered free passage to Israel in the 1950s and many of those who had run the spice warehouses around the synagogue in Jew Town emigrated. But trade continues as wafts of the scent of ginger and pepper leaking out onto the streets attests. In amongst the colourful tourist shops are the unassuming Indian Spice Trade Association, the Oil Exchange and the Pepper Exchange, which still hums with trade but men now sit in booths dealing on phones. It was another kind of world with strange codes, like a secret language, on notice boards for the sales of ungarbled pepper and ready garbled pepper.

Many of the old spice houses have however changed their trade to the export of antiques. Room after room of teak boxes, Rajasthani doors, Chettiar enamel tiffin carriers and Chinese pots wait in the half light ready to be shipped anywhere in the world. In amongst these large warehouses, that are part museum to those that can’t afford it and part shop to those that can, are the smaller tourist traders. “Hello, hello, hello,” they call, “looking is free”. Mirrored belts glint in the sun, alongside lacquer boxes, oldish bronze statues and black and white photographs of grandfathers, grandmothers, mothers and sons. Strangely, little is from Kerala or Kochi for that matter, whether it is new crafts or old. Browsing these stores I meet the new invader, the tourists.

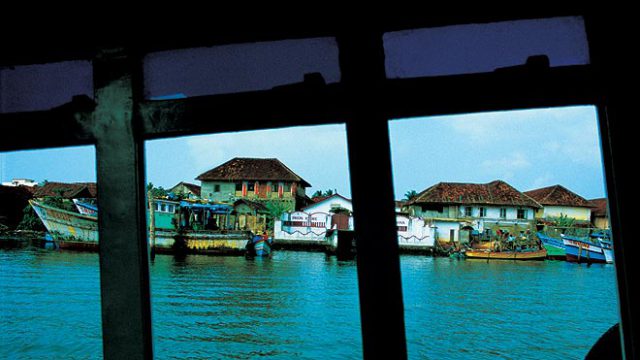

The sheer size of the influx makes a mockery of the sign in the renovated dark wood and whitewashed hotel, the Old Courtyard — ‘You are walking on history, kindly tread lightly.’ Tell that to the hordes of international and local tourists down at the iconic cantilevered Chinese nets, brought from the empire of Kublai Khan. Here fishermen still sell the morning catch of live crabs, red snappers, shark, prawns and pearl spot but they have to jostle with the tourists, the piles of seaweed and those trying to sell mini nets, wooden snakes and fish that they will clean and cook for the tourists on the spot. The nets themselves, which look like lace handkerchiefs that have just gently been dropped by a lady’s hand, are still in working order. I doubted it at first but huge tankers passed me proving the depth and dolphins barely a hundred yards away showed the rich sea life in what seemed like a small river. The place though was comical, as tourists stood at the nets taking pictures of a passing spice boat, except on the boat were more tourists taking pictures back at them of the nets.

Even as the sun set and a boy danced in the waves as though he were alone and free, I felt trapped in a tourist merry-go-round and so headed back into the medieval settlement of pastel houses and narrow alleys. Walking around I realised even the street names mapped out the history of Kochi. Down Dutch Cemetery Road, Rose Street, Princess Street, Calvetty Street, Church Road and I came across the house where Vasco da Gama lived and died. It was now a homestay, tourist information stall and café, and I thought ‘this is living heritage’. I asked to see inside and found school children doing their homework in the blue glass portico. Excited I entered the main room but it had been split by a new wall and a toilet had been added in a corner of the room. I winced at the insensitive conversion and asked the owner when he bought it to make it a hotel. No, he said, his family has lived there for four generations. “I only charge seven hundred and fifty rupees. If I were a palace in Udaipur I would charge five thousand. Seven hundred and fifty is enough for me to maintain the heritage and my survival. Some people don’t like it. They say it is not cute. Whatever, I have lived here for 43 years and I will continue to do so tomorrow, if I am alive tomorrow, if I survive.”

Business is still business then in Kochi, though the nature of it might have changed. The port moves with the times reinventing it and trying to swallow its new invaders, though they plunder its resources, then spices now water. Still any philosophical debate about tourism or what makes good ‘living heritage’ and what doesn’t, for me another tourist, suddenly felt arrogant standing in front of a man who was simply finding the best way to survive in modern Kochi.

The information

Getting there

The Nedumbassery airport is an hour’s drive from Fort Kochi on the Ernakulam Bypass. An Indian Airline Level 4 ticket from Delhi will cost you around Rs 8,000. Jet, Sahara, Paramount and Kingfisher also fly to Kochi. Mangala Express and Kerala Express are the two daily trains from Delhi. The Trivandrum Rajdhani (Rs 2,330 on 3A) runs twice a week.

Where to stay

There are good and cheap hotels on the mainland town of Ernakulam, but stay in the old town if you can. Most attractions can be reached on foot and the streets are worth a wander. The Taj Malabar on Willingdon Island (0484-2666811/2668010; Rs 5,000-14,000) and the Malabar House (2216666; Rs 5800-11,900) are beautiful properties. Kimansion (2216730, Rs 2,500-4,000) is a picturesque homestay on Napiers Street.

Attractions

St Francis Church is open from 6am-7pm and the Santa Cruz Basilica is open from 9am-1pm and 3-5pm. The Pardesi Synagogue is open from 10am-noon and 3-5pm. The Synagogue is closed on Friday, Saturday and Jewish holidays, as it is still a working Synagogue. The Mattancherry Palace is open between 10am and 5pm.

When to go

The best time to visit Kochi is between September and May.

Where to eat

The Kashi Art Café is in a lovely ramshackle building and has great coffee and cakes. Malabar Junction is a chic restaurant with a seafood-based fusion menu. Cheaper, but without the ambiance is the Elite Restaurant, where you can get good fish. For the best biryani in town, go to Rahmatullah Hotel, better known as Kaikka’s after the chef, in Mattanchery.