Early last year, it occurred to my wife and me that neither of us had seen India for more than 30 years. We’d been living in India, certainly; we’d gone to Bombay and Delhi on visits; and even when we’d lived in England in the 1980s and much of the 1990s, we’d returned to India frequently, sometimes for four, even five, months in a year. But to travel through India with no object but to see it — this we hadn’t done since we were children, as helpless, if willing, participants in the care of our parents. The memory hadn’t gone away: of horizons, milestones, trees marked by a single white stripe, the table-tops in dining rooms in guest houses, the front seat of the Ambassador, the temples and inviolable tanks, tangerines being peeled open by someone else, the dark glasses worn by a man getting on to a train. All this had added up, for some reason, to leave an astonishing impress upon us, such as few other countries have done.

No one in their right senses, it seemed, would forgo a journey to a hill station or to Bangkok or even further away for a holiday in Orissa — an hour’s journey away by air from where we were, Calcutta. But Orissa was part of our itinerary as children: I’d retained very little of it except the long redstone corridor of the BNR hotel in Puri, the violence of the waves, and arriving one evening in Bhubaneswar and stopping at a stall, lit by an electric bulb, selling trinkets that were made of shell and bone. (After 35 years, I noticed those stalls and those trinkets again.) It was as if we were trying, my wife and I, to reassemble the elements of a puzzle: different childhoods, during which we were unaware of one another, but the same inexhaustible, restless affection for their common remnants as we began travel out of home through ‘our’ country. To travel was to recognise our pasts had converged several times unwittingly; it was to remember for, and against, the other.

A little more than an hour after we — my wife, I, and our eight-year-old daughter — had set out from Calcutta — and 35 years away from my last sighting — I was in Bhubaneswar again, this time when it was still daylight, soon inside a Maruti Omni going down the wide governmental avenue from the airport to the town, confronting once more the allotments of cows, traffic policemen, intersections, and clusters of vehicles of which so much of our lives and our first arrivals in India are constituted. The combination of patrician, Nehruvian planning and vernacular disorderliness feels at once new and ancient as we return to it in our towns; we’ve been here before, something in us will say; and — Why are we here again? And yet, in the right kind of light, at a certain moment, it can appear deeply suggestive — this kinship and slight antagonism we feel for what is our country, and what has been, for several decades, our nation. It’s fading, though, this nation, as it unfolds in a partly comic spectacle through the road from the airport, with its frayed edges, its imposing width, its hoardings, signs, and instructions. The eye began to drink in, as we saw more of the city the next day, the tranquil sanctums in which the recent five-star hotels had sprung up, the looming façade of a hospital for the rich, the glass hives of IT companies, the slow, luxurious patios of Café Coffee Days. Bhubaneswar: from pilgrimage town to capital city to, now, another, increasingly familiar transformation.

I won’t describe, here, our next two days there, the trip to Konark and further on to Puri, the rediscovery of the BNR hotel in its mournful, mysterious abeyance, awaiting purchase. I’ve spoken of some of these elsewhere. Let me mention, in passing (it’ll soon become clear why) that, returning from Puri, we stopped before the white, living current of the Chandrabhaga, a name that was familiar to me because of the literary magazine of the same name I’d read with excitement in my late teens (such was the bookish, metropolitan shape of my youth, that an ancient river was less real to me than a journal of Indian writing in English). Back in Bhubaneswar, we’d tried to change the date on our airline tickets, and leave a day earlier. But we couldn’t cancel. We had one extra day now — a Sunday. I asked my old friend Jatin Nayak, who’d shown us every generosity during our visit, if we’d have time to visit Cuttack.

Part of the reason for my curiosity was my brief acquaintance, many years ago, with Cuttack in Jatin’s own writings. Jatin is a translator of distinction, and a teacher of English literature at Utkal University; but he’d started out as a gifted short story writer, and had also been an abortive memoirist. It was in the handwritten pages of an incomplete memoir he’d begun in Oxford (where I’d first met him) that I’d read about his Cuttack, mainly about Ravenshaw College, where he’d studied. I’d never forgotten the vaguely remorseful but droll immediacy of that account, which had made Cuttack seem like a nerve centre; nor the fact that Jatin had told me then, at the end of the 1980s, that it was already a marginal city, a great colonial town and a centre of culture that had paled — like so many others, like Allahabad, Dehradun, Ajmer — alongside the rise of the major metropolises, especially Delhi and Bombay, after independence.

The other reason for my desire to go to Cuttack was Jayanta Mahapatra. Part of that generation of poets who’d begun to work in English in the 1960s — perennially youthful, perennially in transition, without any proprietorial claim to either canon or tradition or language — Mahapatra was one of its most unusual practitioners: neither a romantic nor a modernist, direct and veiled at once, he’d created a private, sensuous diction that had changed little over the years, but had remained strangely resilient and tenable. He was in his seventies, recovering from an illness from which, I heard, there had been little hope of recovery. At the age of 18, I’d innocently sent him, in his capacity as the editor of Chandrabhaga, a few poems; he’d replied from his fabled address in Tinkonia Bagicha — a long letter, full of kindness and warmth, promising, too, that he’d publish four poems. That letter had meant a great deal to me, and it still does.

Going down the Calcutta-Chennai Highway (National Highway 5), it takes about 45 minutes on a Sunday afternoon to reach Cuttack from Bhubaneswar. It’s flat land you pass through, half-heartedly industrialised, unconvincingly agricultural, touched everywhere by light, by human endeavour (belatedly abandoned in some places, tentatively resumed in others), by poker-faced state intervention. Entering Cuttack and straightaway taking the Ring Road, we discovered a vista of real majesty: an interminable line of colonial bungalows facing the waters of the river Katjodi, which is a branch of the Mahanadi. Each house is distinct from the other, so that you feel you’ve hardly had time to take them in as the car goes by; like all residences that face water, they have an air of looking upon, indeed configuring, something intangible but immediate — like the future or the past. It would have been the future once. This first glimpse of Cuttack plunges you at once into what can neither be grasped nor forgotten; into, essentially, a history. Some of the bits of information tantalise and conceal as much as they give away; that one of the houses had been Naba Krishna Chaudhuri’s, an important figure in the freedom struggle; that some of the bungalows were owned by Bengalis.

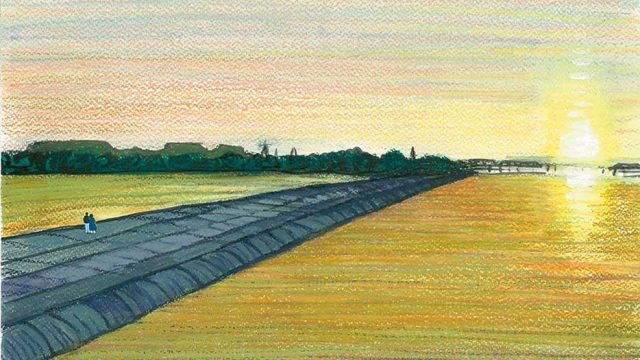

Leaving these houses and turning, we came to a long, intermittently built up road that ran past the Mahanadi; vast, uncanny expanses and scrubland now, since the ‘great river’ was dry. I thought of Kurosawa’s Ran, the windswept plain on which the mad, homeless king wandered, enraged and inconsolable. The dry bed of the Mahanadi invoked some extraordinary theatrical episode; Jatin used to come here once, cycling from Ravenshaw College, to dawdle and daydream. From there he’d go up to where the Katjodi and Mahanadi merge, to contemplate, presumably, the immense body of water; which was now, we found, as we stood on a low wall the British had built, watery only in parts. This was Apu’s world, out of Aparajito; its bleak magic and epiphanies hadn’t absolutely vanished, but the sort of human being who’d been in transit through it — nameless, giving it value — had mutated into ourselves.

By the time we returned to the Ring Road and found ourselves in the town — driving past the stadium and the 150-year-old Cuttack Club, asking for directions to Tinkonia Bagicha — it was dark. We’d reached a square; we were very near Jayanta’s house, but didn’t know where it was. A procession went by — working-class women holding what looked like chandeliers — a wedding procession. And then, in a tiny bylane, on the border of all this activity, but — as is the case with such places — ensconced and distant, we found it: the house in Tinkonia Bagicha, the home of Jayanta and Runu Mahapatra, as well as of Chandrabhaga, which had been given — with the help of the poet Rabindra Swain, who dropped in that evening — a second lease of life.

Jayanta, too, in spite of his frailty, had had a fresh lease; and, slightly mortified at first because of the illness, but genuinely happy, it seemed, to see us, he was soon in full flow and no longer a sick man. My wife and I marvelled at the house. We marvelled, too, at Jayanta’s exceptionally beautiful and gracious wife, Runu. Both house and wife were living emblems of a world we’d adored as children — the genteel, hospitable spaciousness of the first two or three decades of independent India — and whose exact moment of passing we’d never pinpointed or even noticed, except at moments such as these. Had that gentility and spaciousness ever been real? It was not for us, now, to go deep into that question, but to record that, in some way, those impressions had been formative to us. The house, with its courtyard, its book-lined sitting room, and Runu Mahapatra were related to each other in a simple and practical way: it was hers. Tea and biscuits arrived; and, as Jayanta told us of the hesitancies of his first attempts at poetry (he’d been, after all, a student of physics), and took out a volume of Contemporary Authors that contained a short memoir, Runu Mahapatra — especially as we were exclaiming over a wedding photograph in the book, and also enquiring about the house — explained how she and her mother-in-law had never got on, and how they’d moved to this house (which was her family’s) some years into the marriage. This made sense; Jayanta inhabited the house, and had left his mark upon it (the books, the visitors), but Runu, to me, suggested the whole milieu, now invisible, it had belonged to.

After 40 minutes, we reminded Jayanta he had not been well. We rose; embraced; shook hands. I had no premonition of when I’d be in Cuttack again. Runu Mahapatra saw us off to the car, and stood in the shadows, waving. As we emerged from the congested heart of town, Jatin pointed out the dimly lit exterior of Ravenshaw College. On the Calcutta-Chennai Highway, our car had a puncture, and we took shelter in a ramshackle but clean and lit tea shop in the midst of a universe that was quite dark, except for the headlights of the mythic, minatory lorries hurtling past; somewhere, there is a photograph of that moment inside the tea shop, taken by my wife. Can one claim to have properly explored this variegated country without experiencing a puncture? Moreover, travel, inasmuch as it is movement, is also parting and death, predictable forgetting and unexpected recall; as I write this, news comes in of Runu Mahapatra’s passing last week. This is odd, and, like many other things, couldn’t have been foreseen: next to her happy but ailing husband, she had looked bright and self-possessed, and, of course, protective of her companion. Life, like a new place, misleads and surprises us; and gives us a few snatched moments where, for a while, we believe we know where we are.