They say that the camel is the symbol of love, but eyeballing my decidedly stinky steed, a creature easily 2.5m tall at full stretch, and very hairy with it, I just wasn’t feeling the attraction. Camels in Uzbekistan aren’t given names by their owners, which seemed a bit unfair, and so I called him The Donald in honour of the US’s similarly bouffant-haired (and definitely un-lovely) president.

Once properly acquainted—which involved me climbing onto The Donald’s back as he lay lazily in the sand, and then screeching like a banshee as he lurched into a standing position—we were off. If there is a single image which epitomises the romance of the Silk Road, it is surely the sight of a two-humped Bactrian camel stepping gracefully across the desert sands.

The shadows were long, the light was fading, and the September air was still warm. For a few minutes, it was absolutely idyllic. Then The Donald caught sight or smell of a lady camel and set off like a thing possessed. I gripped the saddle and the fur on the back of his neck, clinging on for dear life. A camel in canter is neither graceful to behold nor comfortable to ride, and I feared that my end was nigh.

Thankfully (for me and for the lady camel in question), The Donald was diverted at the very last moment by a particularly tasty bush. Food, it seems, came ahead of lustful urges. And who could blame him? Food can be hard to come by in the desert, but there’s no shortage of other camels.

In central Uzbekistan, the Eurasian steppe gives way to the sands of the Kyzylkum Desert. It’s generally flat, gritty, with occasional scrubby plants. But the Nuratau-Kyzylkum Biosphere Reserve where I met The Donald is an accidental oasis around a lake. I say “accidental” because until 1969 there was no lake here at all.

Aydarkul (which means Aydar Lake in Uzbek) was created when floods burst a poorly constructed Soviet dam on the Syr Darya River. Water, which would otherwise have flowed into the Aral Sea, instead submerged large parts of the desert. Subsequent flooding expanded the new lake, and Aydarkul is now 250 kilometres long and 15 kilometres wide. It’s a haven for migrating water birds, golden orioles and the southern nightingale.

I came to Aydarkul with a gaggle of girlfriends, eager to see Uzbekistan’s wilderness. The country is rightly famed for its incredible Silk Road cities—Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva, all three of which are Unesco world heritage sites—but the natural landscapes are often overlooked. It’s a pity because there’s more to Uzbekistan than its built environment. There’s a sense of peace in the desert which you just don’t get in urban areas, and it’s one of the few places where you can still experience the nomadic culture which has been erased almost entirely from modern Uzbekistan.

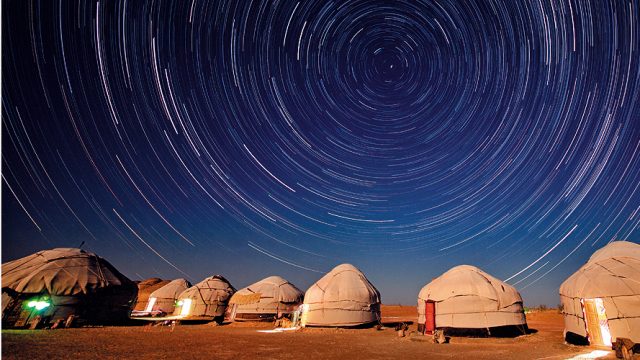

Our desert experience centred on the Nurata Yurt Camp, a community based tourism initiative that creates livelihoods for a number of families living in the biosphere and neighbouring villages. A ring of traditional Kazakh yurts, each one made of felt stretched across a criss-cross wooden frame, surrounds a bonfire site and shares communal facilities. It might seem strange that there are Kazakh yurts in Uzbekistan, but the reality is that Kazakhstan is but a short distance away. Ethnic Uzbeks were historically traders—settled people—and the Kazakhs were nomads, herding their flocks back and forth across the steppe and desert. The national border between these two countries was a 20th-century invention, and today there are still large numbers of ethnic Kazakhs (not to mention Tajiks, Turkmen, Russians, Tatars, and Karakalpaks) living inside Uzbekistan.

The round yurts blend in with the desert’s natural colour palette. I stooped through the low wooden door to enter my yurt, and it took a moment for my eyes to adjust to the darkness. There was a noticeable temperature difference inside, out of the wind, and I realised the importance of the sheep wool felt as an insulating material, especially on a cold desert night.

A yurt looks to be a pretty solid structure, and it can survive all manner of ill weather. But the remarkable thing is that it is designed to be disassembled, moved, and re-erected in a different place in record time and with remarkable ease, as is required by a nomadic lifestyle. An experienced family can take apart their yurt in just one hour, and it packs down small enough to be transported on the backs of two camels or horses.

The exterior of my yurt was simple, but like many homes around the world, its owners had gone to town in decorating the inside. Hand-sewn embroideries and other appliqué textiles adorned the walls, interspersed with stripes of shiny silver and gold ribbons. The wool carpets on the floor were no doubt woven in a local village, deep red in colour and richly patterned.

Solid furniture is incompatible with a nomadic lifestyle: everything must fold up, or roll up, so that it can be moved. It was with some trepidation, then, that I flopped down onto my bed, a stack of mattresses and rugs on the floor. The sheet was clean, and unexpectedly the bed had just the right amount of give, neither too hard nor too soft. My joints ached after a day on the road, not to mention my escapade with The Donald, and it was all I could do to fight against the drowsiness I knew would soon shift me into a deep and dreamless sleep.

By now darkness had fallen, and above the yurt camp was one of the greatest, brightest spectacles of stars I’d ever seen. Living in a city you quickly forget how brilliant the night sky can be. It was a cloudless night, and we were miles from the nearest town. A few of our party were drawn up onto the dunes for an even better view of the constellations. But I was intrigued by the yurt camp bonfire, which had begun to crackle into life, and by the musician attempting to unpack his stringed instrument in the firelight.

I didn’t catch his name, but our singer-instrumentalist had been summoned from a nearby wedding party. Already three sheets to the wind, Uzbek vodka no doubt having taken its toll, the poor chap would probably rather have been on the dance floor (or tucked up in bed). But here he was, attempting to belt out tunes that have echoed through these deserts for centuries. I couldn’t understand a word, but his melodies were haunting, travelling out into the inky blackness of the night on the desert breeze. Around the bonfire we swayed in time to the music, breaking now and then into slow, almost sombre, dance.

Standing amongst the dazzling madrassas and minarets of Samarkand or Bukhara, you are a tourist and outsider looking in. There’s nothing wrong with that. But out in the desert, cloaked in darkness, your status in Uzbekistan is something else. You are the latest in a multi-millennia-long line of foreign travellers to have stopped for the night, shared food and drink, stories and folk songs. The ghosts of the past are here, and you are continuing the traditions of the Silk Road.

The Information

Getting There

AIR The nearest airport is Navoi (100 km/2 hrs). Uzbekistan Airways (uzairways.com/en) has direct flights from New Delhi and Amritsar to Tashkent, with onward connections to Navoi. Taxis are available and charge ₹3,500 approx return fare from the airport.

RAIL Bukhara station (225 km/4hrs) has high-speed connections to Samarkand and Tashkent.

ROAD Regular buses and minibuses from Bukhara, Samarkand, and Tashkent serve the closest bus station in Karmana. You will then need a taxi to reach the yurt camp (₹2,600 approx return fare).

Where to Eat & Stay

Many travel companies offer tour packages including a one-night yurt stay at Aydarkul en-route from Bukhara to Samarkand. These include local transport, swimming in the lake, dinner, bed and breakfast at the yurt camp, a camel ride, and live music and dancing around the bonfire.

Kalpak Travel (+41-78-6572701, kalpak-travel.com) is a Swiss tour operator specialising in small group and bespoke itineraries to Central Asia. They have a representative office in Samarkand, professional English speaking guides, and include the Nurata Yurt Camp in many of their programmes. There are no restaurants within the Nuratau-Kyzylkum Biosphere Reserve but all yurt camps and homestays provide meals for their guests. Independent travellers can book yurts, and homestays directly through the Nuratau Ecotourism office (₹2,600, with two meals; +998-90-2650680, nuratau.com).