Seidnaya is a Greek Orthodox convent in Syria, three hours’ walk from Damascus. The monastery sits on a great crag of rock overlooking the orchards and olive groves of the Damascene plain, and at first sight, with its narrow windows and great rugged curtain walls, looks more like a Crusader castle than a convent.

According to legend, the monastery was founded in the early sixth century after the Byzantine Emperor Justinian chased a stag onto the top of the hill during a hunting expedition. Just as Justinian was about to draw his bow, the stag changed into the Virgin Mary, who commanded him to build a convent on the top of the rock. The site, she said, had previously been hallowed by Noah, who had planted a vine there after the flood.

Partly because of this vision, and partly because of the miracle-working powers of one of the convent’s icons, said to have been painted by St Luke himself, the abbey quickly become a place of pilgrimage and to this day streams Christian, Muslim and Druze pilgrims trudge their way to Seidnaya from the mountains of Lebanon and the valleys of the Syrian jebel. In 1994, while on a six-month tramp around the Middle East, I went to spend a night within its walls.

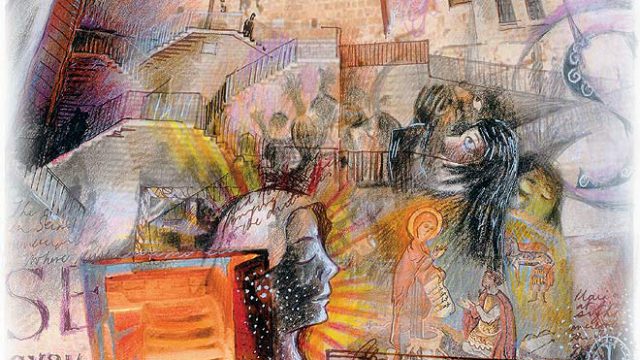

When a friend of mine visited the convent 30 years ago, he said he witnessed a miracle: that he saw the face of the icon of Notre Dame de Seidnaya stream with tears. In the same church I too witnessed a miracle, or something that today would certainly be regarded as a miracle in almost any other country in the Middle East. For the congregation in the church consisted not principally of Christians but almost entirely of heavily bearded Muslim men and their shrouded wives. As the priest circled the altar with his thurible, filling the sanctuary with great clouds of incense, the men bobbed up and down on their prayer mats as if in the middle of Friday prayers in a great mosque. Their women, some dressed in full black chador, mouthed prayers from the shadows of the exo-narthex. A few, closely watching the Christian women, went up to the icons hanging from the pillars; they kissed them, then lit a candle and placed it in the candelabra in front of the image. As I watched from the rear of the church I could see the faces of the women reflected in the illuminated gilt of the icons.

Towards the end of the service, the priest circled the length of the church with his thurible, gently and almost apologetically stepping over the prostrate Muslims blocking his way. It was a truly extraordinary sight, Christians and Muslims praying together in a fashion unimaginable today almost anywhere else in the Near East. Yet it was, of course, the old way: the Eastern Christians and the Muslims have lived side by side for nearly one and a half millennia and have only been able to do so due to a degree of mutual tolerance and shared customs unimaginable in the solidly Christian West.

As I made my way through the Middle East I found no shortage of examples of tensions between Christians and Muslims, but as at Seidnaya I also found myself constantly reminded of what was in many ways a more surprising story altogether: the amazing way in which Christians and Muslims had, until recently, succeeded in living together for so many centuries, in closely knit communities in town after town, village after village across the Middle East. If that coexistence was not always a complete harmony, it was at least, with very few exceptions, a kind of pluralist equilibrium.

How easy it is today to think of the West as the home of freedom of thought and liberty of worship, and to forget how, as recently as the 17th century, Huguenot exiles escaping religious persecution in Europe would write admiringly of the policy of religious tolerance practised across the Islamic world: as M de la Motraye put it, “there is no country on earth where the exercise of all Religions is more free and less subject to being troubled, than in Turkey”. The same broad tolerance that had given homes to the hundreds of thousands of penniless Jews expelled by the bigoted Catholic kings from Spain and Portugal, protected the Eastern Christians in their ancient homelands — despite the Crusades and the almost continual hostility of the Christian West. Only in the 20th century has that tolerance been replaced by a new hardening in Islamic attitudes; and only recently has the syncretism and pluralism of Seidnaya become a precious rarity.

As vespers drew to a close the pilgrims began to file quietly out and I was left alone at the back of the church with my rucksack. As I was standing there, I was approached by a young nun. Sister Tecla had intelligent black eyes and a bold, confident gaze; she spoke fluent French with a slight Arabic accent. I remarked on the number of Muslims in the congregation and asked: was it at all unusual?

“The Muslims come here because they want babies,” said the nun simply. “Our Lady has shown her power and blessed many of the Muslims. The people started to talk about her and now more Muslims come here than Christians. If they ask for her she will be there.”

As we were speaking, we were approached by a Muslim couple. The woman was veiled — only her nose and mouth were visible through the black wraps; her husband, a burly man who wore his beard without a moustache, looked remarkably like the wilder sort of Hezbollah commander featured in news bulletins from Southern Lebanon. But whatever his politics, he carried in one hand a heavy tin of olive oil and in the other a large plastic basin full of fresh bread loaves, and he gave both to the nun, bowing his head as shyly as a schoolboy and retreating backwards in blushing embarrassment.

“They come in the evening, “ continued the nun. “They make vows and then the women spend the night. They sleep on a blanket in front of the holy icon of Our Lady. Sometimes the women eat the wick of a lamp that has burned in front of the image, or maybe drink the holy oil. Then in the morning they drink from the spring in the courtyard. Nine months later they have babies.”

“And it works?”

“I have seen it with my own eyes,” said Sister Tecla. “One Muslim woman had been waiting for a baby for 20 years. She was beyond the normal age of child-bearing but someone told her about the Virgin of Seidnaya. She came here and spent two nights in front of the icon. She was so desperate she ate the wicks of nearly 20 lamps.”

“What happened?”

“She came back the following year,” said Sister Tecla, “with triplets.”

The nun led me up the south aisle of the church, and down a corridor into the chapel, which sheltered the icons. It was darker than the church, with no windows to admit even the faint light of the moon, which had cast a silvery light over the altar during vespers. Here only the twinkling of a hundred lamps lit the interior, allowing us to avoid tripping over a pair of Muslims prostrated on their prayer carpets near the entrance. Sister Tecla kissed an icon of the warrior saints Sergius and Bacchus, then turned back to face me: “Sometimes the Muslims promise to christen a child born through the Mother of God’s intervention. This happens less frequently than it used to, but of course we like it when it does. Others make their children Muslims, but when they are old enough they bring them here to help us in some way, cleaning the church or working in the kitchens.”