I have always fantasised about dancing in a mustard field, my brightly coloured, swirling lehenga set off by the impossibly yellow banks of flowers swaying gently all around.

But I could never have dreamt up the form that my mustard-field fantasy has just taken. For here we are, driving through interminable swatches of mustard; bumping over mud-packed bunds between fields; climbing up and down sandbanks to cross unsupervised railway tracks; negotiating small clearings packed with the inevitable buffaloes and stacks of drying dung. Ehsaan jokes that we won’t lack for sarson-ka-saag if our car stalls in an irrigation channel after nightfall. His driving skills eventually put us back on the highway some distance past the reason for our detour: a roadblock created by irate local residents demanding exemptions from toll payments on State Highway 15A, just west of Farrukhnagar. Even as I mentally recalibrate my mustard-field sequence to include a James-Bond-style car chase, I scan the early-December sky anxiously. Sunset will soon force an abrupt end to our day’s rambles around lesser-known monuments in three Haryana districts close to the National Capital Territory of Delhi — Jhajjar, Gurgaon and Mewat. The drive from Jhajjar to Farrukhnagar, which should have taken about half an hour, has taken us two-and-a-half hours.

The day begins many hours earlier, with our first stop just across the Delhi border, at Bahadurgarh, in Jhajjar district, Haryana. Here, we have to weave through carts full of farm produce to get to our destination — a late-eighteenth/early-nineteenth-century fort gateway. The gate is plastered with political and commercial posters, and there’s a flourishing Ayurvedic/Unani pharmacy in the guard and drum rooms. Unfortunately, this badly maintained gate is virtually the only remnant of the tiny, sixty-square-kilometre ‘princely state’ that existed here until the last nawab, Bahadur Jang Khan, was exiled to Lahore for not helping the British forces in 1857.

Disappointed, we get back on the highway. We drive past a surprising number of large, full and well-maintained village taalabs until we hit the first open playing field that was clearly once an artificial lake, too. There’s an interesting late-Mughal baoli here, and a rare, medieval stone Shiva temple. We stop to admire these unexpected delights, and get drawn into the pretty, prosperous little Jat village, Dulehra, that sits beyond them. Clean, quiet streets are flanked by beautiful doorways; women and old men (almost all called Deshwal) sit in separate groups on string cots in sunlit clearings, the men smoking from long hookahs. But Dulehra is in a time capsule that is perhaps soon to explode: already, the village is empty in the late morning because all the young people are away working in Delhi or Gurgaon, and a major highway link will soon bring big-city life even closer.

We don’t have to look very hard for our next destination: a spectacular set of tombs, all built between 1594 and 1630, with seven of them still standing, is clearly visible from the main road into Jhajjar. They are all built of limestone rubble, and have sandstone facings with copious inscriptions and beautiful carved and sgraffito detailing that are still intact at several places. Even though the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has economised by stretching strings of barbed wire where the gate should be (to keep buffaloes out, we are told), the structures are surprisingly well maintained, surrounded by clean and well-trimmed lawns. This is all the more remarkable because there’s only one person, Pawan Kumar of the Horticultural Branch of the ASI, minding the entire complex, multi-tasking as gardener, cleaner and guide. He tells us the legend behind the main ‘Bua Hassan’ tomb, slipping in the fact that parts of Lagaan were shot here. When the doomed love affair between an aristocratic woman known today only as ‘bua’ and a woodcutter, Hassan, ended with his death in battle, the heartbroken bua built her lover a large, beautiful tomb that she was also buried in, after she died pining for him on the banks of the taalab nearby a couple of years later.

It is now time for lunch, and we repair to the simply-named Shuddh Bhojanalaya dhaba across the road, before getting back on the road to Dujana, which was abandoned by its small-time nawab in 1947, when he and his family fled to Pakistan under pressure from other local residents and incoming refugees. Dujana has some interesting British-era institutional structures built by this last nawab — Mohammad Iqtidar Ali Khan — as well as a ruined palace that still has traces of Italian tiling and sculptural detail. There’s also a courthouse and prison (now a private house — the owners bought it at a government auction in the early 1950s), an old house with a mysterious grave in the basement that is now being demolished and a mosque that has recently been whitewashed and, unfortunately, enclosed in ugly aluminium jaalis. We then wander around the abandoned police station and into what we are told was the safe room for weapons, only to find that we have disturbed a troop of monkeys in the process. They block the doorway, hissing and spitting until our desperate cries eventually bring help. We make plans to flee, still shaking, when a passing maulvi directs us to Dujana’s best-kept secret — the Safed Masjid and the dargah of the fakir Durjan Shah, after whom the town is named. The crumbling, forgotten masjid is kept bravely alive by a small group of loving caretakers, and we slowly calm down in its peaceful environs.

Eventually, we drive out of Dujana, stopping at yet another quaint, abandoned baoli — this one ringed by miniature minars, and now being used to stack buffalo-dung pats and hay. As we discover, this is also the site of a major, twice-yearly, buffalo mandi that we have to negotiate as we get back on the highway. Some distance out of town on the Rewari road, we stop at Gurukul, a privately run ashram — and the unlikely site of the Haryana government’s most major collection of coinage and artefacts from the River-Valley period onwards.

And then we are back on the road, headed southeast to Farrukhnagar, via the mustard-field interlude. At the entrance to the little town, there is a standalone, domed structure called Sethani ki Chhatri that has the most amazing frescoes on its ceiling — various episodes from Krishna’s life, Vishnu’s avatars, plus scenes from everyday and court life that emphasise women’s roles. There’s one scene of women at a well giving drinking water to passing soldiers, and another of a soldier climbing up a balcony for a clandestine rendezvous with a noblewoman. The chhatri, perhaps built by a rich merchant to mourn a beloved wife, is a forgotten jewel in serious danger of soon vanishing through neglect.

We then enter the town through Jhajjar gate, and stop immediately at a very unusual circular bathing well, the Ghaus Ali Shah ki baoli, that we have to approach through an underground path. It’s well maintained and the caretaker, Lacche Ram, who lives on the premises, is kind enough to open it up for us despite the late hour. We are told that the baoli had a secret tunnel linking it to the women’s section of the palace nearby, but this access is now blocked up. Then we go through another existing city gate, Delhi gate, to the ruins of the palace, Sheesh Mahal. Despite several reports that talked about intricate mirror-work on the walls of this complex, we see no glass of any kind anywhere — unless one takes into account the telltale, broken liquor bottles that lie around the place. Farrukhnagar is another former ‘princely state’, whose fortunes first faded when its salt-manufacturing industry was crippled by British taxation. Its ruling elites also suffered setbacks in 1857 as well as in 1947; the local Jama Masjid is now a Sita-Ram temple, and though there is still some amazingly intricate stucco and metal grillwork on the house façades all around, the important buildings are all in various states of ruin.

By this time, it is quite dark, and we decide to return to Delhi. We set off again early the next morning, this time driving southwest through Gurgaon, to pick up where we left off the previous evening. We drive past the very beautifully maintained Pataudi Palace, deciding that it doesn’t need our solicitousness, and proceed towards Sohna, stopping at Badshahpur to trace a historic baoli. We wander with failing hope through a new settlement of construction workers and a girls’ school before finally stumbling on an exquisite nineteenth-century baoli that is steadily sinking into oblivion under the weight of undergrowth and stinking piles of trash. Not the greatest tourist destination, we agree soberly among ourselves, as Sankar Sridhar despairs over the photo opportunities that might have been.

Our sense of gloom deepens as we drive southeast to Sohna, which derives its name from the gold that was once panned in the local river. We walk swiftly in and out of the featureless Shiv Kund hot springs. We despair of locating other promised sites — bits of fort walls, a pair of Tughlak and Lodhi-era tombs, an old masjid (now a temple), until Maulana Kalim of the Shahi Jama Masjid offers to get in the car with us and show us around. The spotless, whitewashed Jama Masjid is itself dramatically located on a hilltop, with a madrasa on the edge of a cliff where earnest little boys in embroidered caps are rocking studiously as they commit the holy book to memory. Our spirits somewhat lifted by this charming image, we push on towards Taoru, where we again find we have to drive around in circles, seeking out old-timers for guidance, before we negotiate twisting mazes of back alleys to get to the set of seven amazing fourteenth- to sixteenth-century tombs on the forgotten edge of the town. Despite being the focus of ongoing restorations, the tombs are primarily storehouses for… you guessed it, drying dung cakes, all neatly stacked almost to the tops of the doorways so it’s impossible to even enter most of the structures. The shrine of the nameless Pir Baba around whom the complex of tombs probably mushroomed doubles as a multi-faith temple, with a line of tiles featuring a spectrum of gods and holy places on the back wall and a brass bell out front.

And so we are back on the road, after a chai stop at a little wayside stall where we are served by the charming Arbina on behalf of her father. Perhaps twelve years old, she claims vigorously that she goes to school, but cannot tell us its name. We now head further southeast, to Nuh — seventeen kilometres and twenty minutes away, we are assured by Google Maps. Well, the mapmakers didn’t take the relentless procession of trucks carrying construction material into account, and the journey takes two hours, with no hope of bypassing the block because there are only sheer cliff faces to either side of us. So we settle back and enjoy the rousing music provided by the tractor-powered jugaad vehicles stuck on the road with us, and eventually bump along to the quaint little dargah of Sheikh Musa, a grandson of Baba Farid who lived and died here in the early 1300s. Once there, we climb to the top of one of the slender minars on the main gateway of the dargah, to test out what we’ve been told about it. It’s true, though I’m not sure my head can bear it for too long: if you shake the walls of one of the minars, it rocks… and so does the opposite minar, several dozen metres away!

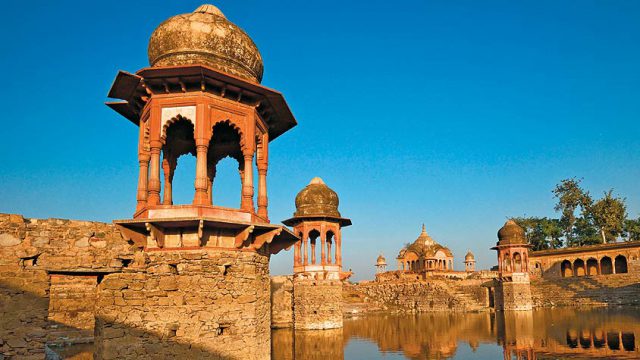

Then, finally, we head out to our last destination, Chuhimal ki Chhatri and taalab. By now, the routine is familiar: ask repeatedly for what you want from locals who are visibly baffled by your interest, and finally stumble on an amazing site that is in an equally amazing state of disrepair and abandonment. In this instance, the walkways around the taalab, still full of stagnant water, are being put to good use by Billu Tent House for drying carpets, and the elaborate, exquisitely detailed chhatri, built by some long-forgotten trader in the most elaborate eighteenth-century style, is a useful site for a card game that doubles up as a handy toilet.

By now it is once again nightfall, and we hasten to take on the modern maze of Gurgaon’s road network as we drive back home to Delhi.

The information

The route

DAY 1: We drove west out of Delhi on NH10 and took a left turn on NH71 (which is also Haryana State Highway — SH22) a few kilometres beyond the border of Delhi. Within minutes we were in Bahadurgarh, in Jhajjar district. Then, we got back on SH22 and drove for about 14km, looking out for a red-washed structure crowning a baoli next to a large playground on our right. This was Dulehra village. We drove another 14km westwards until we hit the edge of Jhajjar town. Soon the large park that encloses the marble-tiled Bua Hassan ka taalab appeared on our left. Immediately after were the Jhajjar tombs, also to our left. Next, we took a right on NH71, northwards towards Rohtak, and drove for about 10km, until we found the turn for Dujana (there was no board to guide us, so we just asked). To find the Gurukul Museum, we returned to Jhajjar and drove south on NH71, towards Rewari. (5km outside of Jhajjar, we looked for signs on our right). For Farrukhnagar, we returned to Jhajjar and drove for another 26km on SH15A, entering Gurgaon. To return to Delhi, we continued on Pataudi Road to NH8 and cut through Gurgaon.

DAY 2: To reach Badshahpur from Delhi, we drove west on NH8, then headed 10km southwards on Sohna Road (SH13). Thereafter, we drove straight down south to Sohna, 17km away, on the same road. Then, we headed west on Taoru Road (SH28) to Taoru, in Mewat district, 14.5km away. From there, Major District Road 132 took us the 17km uphill to Nuh, also in Mewat. SH13 brought us back up to Sohna (roughly 21km), from where we looped back to Delhi through Gurgaon.

Where to stay

If you don’t want to return to Delhi at the end of Day 1, you could stay at the Pataudi Palace (from Rs 5,871; neemranahotels.com). Or you could stay at the Rosy Pelican Guest House inside the Sultanpur Bird Sanctuary near Farrukhnagar (from Rs 3,500; sultanpurbirdsanctuary.com). To the south of NH8, there is the Westin Sohna Resort and Spa (from Rs 11,000; starwoodhotels.com).