This house is not yours. You think it is mine. But even those that come after me won’t live here for eternity…” The wine from lunch still sloshing on the insides, I know that this—a homily etched in Romansh on the façade of a traditional house near St Moritz—is by far the only sobering device in the Engadin Valley. (Okay, this and our guide Guido Ratti’s jalopy.) Everything else is a fever dream.

Only, I can’t tell anymore. After pretending like everyone else here that money doesn’t matter, all the while spending wads and wads of it, window-shopping for pink diamonds seems natural. Laderach chocolates? Now, there’s a steal. Yet, whether you land by private jet or on the back of the Swiss Railways—blazing a red trail through the white Alps, over bridges with ungainly legs—you can never be sure you’ve arrived at St Moritz.

With no Swiss accounts to my name and not one common acquaintance between Lakshmi Mittal and me (his holiday home here has gold-plated radiators!), I depend on my legs to take me where my tourist franc won’t go. Pounding the streets soon after dawn, I hope to see what hoity-toity St Moritz looks like before it slips out of its pajamas and fixes its tousled hair. When its empty roads are emptier still. For there’s something disarming about mornings, the pale half-light dulling the edges of a new place, no matter how strange, how foreign.

I’m about three miles from the centre of town—to be accurate, at a ‘village’ called Surlej. Somewhere between the ice runs of Piz Corvatsch and the mirrored Lake Silvaplana. Determined to take in as much as my eyes and lungs will allow. No camera slung around the neck, no notepads that encumber.

A few hundred metres down though, the Alpine air and my frozen extremities bring my already slow jog to a halt. Before me lies the blue mirage I was chasing all along. Glimpses of its spangled surface caught between rows of snowbound cottages and parked cars. At this hour, the only signs of life around it are families of ducks and coots, unruffled by the cold water or the new pair of eyes that scans them.

By the time I make my way back, huffing and puffing up the steep road that leads to my hotel and to breakfast, the ski lifts at Corvatsch are up and running. Men and women walk alongside in ski boots—heel first, in the manner of tin soldiers. The bakery has a pile of bread on the bench, and there’s a new person smiling at me from behind the reception desk. The newspaper is not at my door yet. Thawing, I think of her.

There she was, executing a perfect backbend against the wintry Alps in her bathing suit and heels. This, before butler-service breakfast and lawn tennis in long skirts and cloche hats… Yet, charming as a 1930s B&W film can be, it doesn’t quite give you the full picture. To know why one would risk pneumonia or herniated discs, or both, on a holiday in the world’s oldest winter resort town, one would have to be there. Backbending, preferably, at the Badrutt’s Palace. (The word ‘palace’ is an allusion to its size and style, not pedigree.)

It’s the kind of establishment that smells of pine and old money. A place where, no matter how many private jets you own, chances are, the chap next door owns more. We had driven past it that afternoon before we took a train to Alp Grum. We had wandered along it, ogling at luxury boutiques and fur-clad ladies at the local Rodeo Drive, Via Serlas. We had talked about it from the moment the trip was planned, and a dress code issued; always in hushed tones, lest we sully it somehow.

Invited to dine here, I feel like an impostor. The faux fur in a coat rack of minks and sables. The prospect of a good meal, however, can make most things more palatable. Even playacting.

Half-pretending to own the Raphaels and Madonnas staring down at us, I follow my hosts down endless corridors and halls. The train of my dress threatening to go up in flames from the flickering candles (the only illumination), I squint down a spiral staircase at the bottom of which awaits the cellar and the first course of our ‘roving’ meal.

Several glasses of champagne later, second course follows under a grand chandelier at Le Restaurant. All very Belle Époque. Now, the best dinner table conversations are those that hasten the arrival of dessert. So it is with some surprise that I note I’ve nearly forgotten about dessert this evening. In Switzerland. The land of milk and honey and chocolate. The man responsible for my oversight is above blame, of course—sharing, as he is, an heirloom tale of love, longing and serendipity in the heart of St Moritz; a tale as heady as the Alpine air and the contents of my crystal flute. Apparently, shortly after accepting an offer to be the director of sales at the Badrutt’s Palace, Lars Wriedt stumbled upon a stack of his grandfather’s writing pads. Between the pages were unsent letters to his future wife, then the chaperone of a French heiress on vacance. An heiress on vacance at the Badrutt’s Palace!

Stories such as these, of chance and felicity, have kept Badrutt’s in business and its tariffs legendary through the Great Wars and Depression, N-bomb threats and recession. The Aga Khan honeymooned here. Audrey Hepburn and Greta Garbo swanned in through its tall, swivelling doors. From his perch at a suite named after him, Alfred Hitchcock spotted his inspiration for The Birds —a flight of jackdaws riding the thermals of the Maloja wind, circling above the frozen lake of St Moritz. A lake that also served as a hangar for the brothers Wright once. More recently, the Academy Award-winning composer of The Grand Budapest Hotel, Alexandre Desplat, confessed to the concierge that Badrutt’s was his chief muse.

Yet the greatest legend of them all is the one that turned St Moritz into the ultimate Alpine playground for the rich and famous, exactly 150 years ago. Johannes Badrutt, owner of the Kulm Hotel and father of Caspar, who later built the Badrutt’s Palace, wagered his British guests in the autumn of 1864 that were they to come back in winter, there would be plenty of sunshine to greet them, no matter how deep the snow. (The tourism board still flogs the old ‘300 days of sunshine’ horse in a mostly grey Europe.) That winter, the guests came back to discover the sun and the giddy highs of riding a bobsled down some of the hairiest slopes on the Continent. Eventually, curling and tobogganing, cresta and ski runs pushed adventure and the fortunes of St Moritz off piste.

But all things that go up must come down, surely? A theory put to test on more occasions over the last few decades than the inhabitants of this resort town would deign to admit. Though the Swiss may have (mostly) stayed out of trouble through the 20th century, they haven’t been entirely insulated from the world and its problems. While Western Europe settles the more plebeian questions of illegal immigration and debt, for instance, St Moritz grapples with First World issues of its own. Its current quandary? New money, or change (depending on whom you ask).

Our guide Guido, a retired bobsled announcer and glider who counts the Prince of Monaco as a friend and drives a beat-up car he can’t bear to part with, is only half joking when he says we kept him up all night. In this part of Switzerland, a tour group of Indians is still an odd thing. He didn’t know what to expect, or if we’d hike in saris.

Yet, one suspects, the Indian chef now employed by the Badrutt’s Palace is just as welcome as the fur-clad Russian ‘philistines’. As are the Mittals and the Bajajs. Perhaps, the most prominent embodiment of this spirit, bang in the centre of town, is British architect Norman Foster’s kidney-shaped Chesa Futura or house of the future—hardly Swiss, barely terrestrial. Yet the locals walk by it without comment or censure. Many even take pride in it. Its neighbour, a Lutheran Church with a handsome steeple, looks deceptively different from the Chesa. But inside, the only thing traditional you’ll find is an old organ, overwhelmed by changing art installations and candy-coloured chairs. Guido is not entirely sure he likes this last amendment. Neither am I.

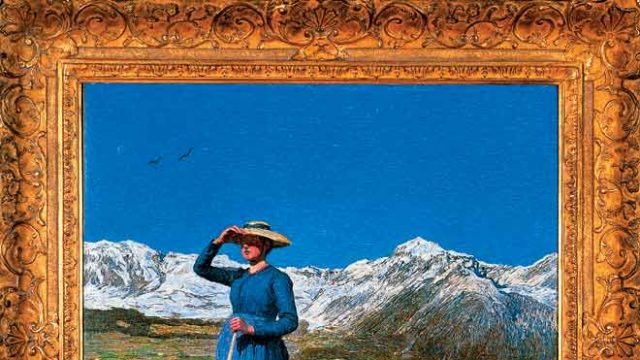

As if to make up for the modern tokenisms at the church, Guido leads the way to another new-old temple of change perched over the four main upper Engadin lakes—St Moritz, Silvaplana, Sils and Champfer. Trundling up in a bright red funicular, our portly Santa Claus-y guide tells us the vantage point of Muottas Muragl and the now energy-plus Romantik Hotel is about 4,000 steps on foot. At the top, conversation runs as thin as the air. Not because the sweeping views of the valley leave one breathless—as they should. But because the north wind picks up and finds us cowering in a snowbound cabana, drinking deep from a borrowed hipflask. When the wind finally forces everyone indoors—abandoning plans to follow the Philosopher’s Trail up to the cottage of the artist Giovanni Segantini—the sun shines again, this time in a PPT. A proud proclamation of the fact the 110-year-old Romantik Hotel may now be poorer by 20 million Swiss Francs, but it is richer by 1,00,000KW/jahr solar energy. North wind notwithstanding.

Back at the train station, return ticket in hand, I reflect on the the idea of St Moritz that I had stubbornly carried around with me. Surely a place built to please the rich could hardly have room for those who can’t tell cashmere from mohair? Surely a place that has allowed mango lassi and tandoori jhinga to invade its menus is not ‘authentic’ or Swiss enough? Gstaad must be right about the promiscuity of St Moritz. An ageing beauty following the example of “high-class ladies of doubtful virtue”, who according to author Peter Viertel once roamed its streets.

Clutching my bag of cheese, chocolate, birn brot (a pear and nut bread) and a buttery walnut pie, I wait for the train to Zurich. A tourist with a pair of skis yells, “Ciao, bella!”, reminding me that Italy is but a few miles away. The train pulls up. A lady greets a fellow passenger in German. Someone from my group plays a Bollywood tune. And like the lines of a forgotten song, the Romansh etching comes back to mind —“This house is not yours. You think it is mine. But even those that come after me won’t live here for eternity…” So be it.

The information

Getting there

We flew Premium Economy on Air France to Zurich via Paris. Air France has daily flights from Delhi to Paris and several connecting flights every week to Zurich (from about INR 65,000; airfrance.in). Unless you own a private jet, the best way to get to St Moritz is by train from Zurich via Chur—there are connections almost every half hour. Get a pass from Rail Europe (from INR 16,500; raileurope.co.in) or Swiss Railways (from CHF210; sbb.ch/en/home.html).

Visa

You will need a Schengen visa to travel to Switzerland (vfsglobal.ch/switzerland/india; visa fee: INR 3,900 plus INR 952 service fee).

Currency

The euro is widely accepted in Switzerland, although it’s good to keep Swiss francs handy as well (€1 = about INR 70; CHF1 = INR 68)

Where to stay

If you can afford to stay at the Badrutt’s Palace (from about CHF300; badruttspalace.com), book ahead and try not to gape if you run into George Clooney in the lift. With period furniture, some of which was left behind by guests who liked to ‘feel at home’ wherever they went, upholstery that is specially created in Belgium, and artwork by the likes of Raphael, the hotel is a museum by equal right. The Palace’s older kin, Kulm Hotel (from CHF290; kulm.com), is also sought out by those who like to step back in time.

We stayed at the Nira Alpina (from about CHF270; niraalpina.com), near the village of Surlej, about 5km from the centre of St Moritz. The newest kid on the block, it may not have rafters the size of redwood trees, but its modern, minimalist premises have plenty of quirky details that can keep you occupied even if you find yourself snowbound. However, if you can ski, it will be hard to stay in since this is the only ski-in-ski-out hotel in the valley with a private walkway connected to the ski lifts.

What to see & do

You’d hardly expect to meet the world’s largest whisky collection at St Moritz. Or wouldn’t you? Sign up for a whisky tasting session at the Hotel Waldhaus Am See (waldhaus-am-see.ch/en-us), which has a staggering 2,500 varieties of single malts and Scotch whiskies collected over 25 years. Claudio Bernasconi, who had first started collecting by requesting his guests at the then 12-room hotel to bring the tipple of their country, has over the years even succeeded in getting Glenfiddich to produce a limited edition for them. The only other person who has been extended such a favour happens to be the Queen of England.

On a clear day, take the funicular up to the energy-plus Romantik Hotel at the 2,456m-high vantage point of Muottas Muragl (muottasmuragl.ch/en) and follow the Philosopher’s Trail to the painter Giovanni Segantini’s hut. Later, if you like, visit his museum in town (segantini-museum.ch).

In St Moritz, embrace the tourist in you with a horse-drawn carriage ride that takes you through Alpine forests and skirts lakesides, tucked under blankets and fur. Before you take the train back to Zurich, walk down to the open-to-public-round-the-clock St Moritz design gallery lined with posters near the station. Also, drop by if you can at the local confectionary at Hauser (hotelhauser.ch) and at Sennerei (sennerei-pontresina.ch), an artisanal cheeserie in the neighbouring towns of Samedan and Pontresina.