At noon in Haryana, it’s well over 40 degrees in the shade. I’m not in the shade though. I’m out in the open, grappling unsuccessfully with an unwieldy camera and tripod, and doing an even worse job of convincing a nervous redwattled lapwing that I’m not interested in her eggs.

She’s doing the classic ‘let’s pretend I have a broken wing and get this bloody mastodon to move this way before he mashes my clutch’. The heat is stifling and the shrill didyoudoit-didyoudoit insistence of the agitated avian forces me to take a detour through the local dumping ground. Looking beyond, I stop, entranced.

Its 2005, when even the smoke from a cigarette can get you censured. And here is a hulking great, fully-functional steam engine. Its black and buff, with a naked display of potent-looking piping, pistons and valve gear. This is utterly in-your-face power of a kind that a big diesel engine can only hint at, and electric locomotives elide altogether.

I’m walking toward the steam loco shed at Rewari Junction, not far from Delhi, and it’s the mother lode for people like me, who are loco about steam. It’s not hugely well-known, but steam engine fanatics, primarily from the UK, Japan and Europe, have been visiting the Rewari Steam Centre in a steady trickle. There may be other places to see beautifully preserved steam locomotives, and there are occasional opportunities to see them run, usually for special or commemorative runs. But Rewari is one of the few places in the world where you can regularly see a workingsteam engine in all its clanking, smoke-pumping glory.

Today the centre is the only locomotive shed on Indian Railways’ huge network that maintains steam engines in working order. It has 10 broad- and metre-gauge steam locomotives. Rewari was for many years the biggest junction on the north Indian metre-gauge network, possibly the biggest in all of India. The steam shed dates back to 1873, which makes it India’s oldest and one of the oldest in world.

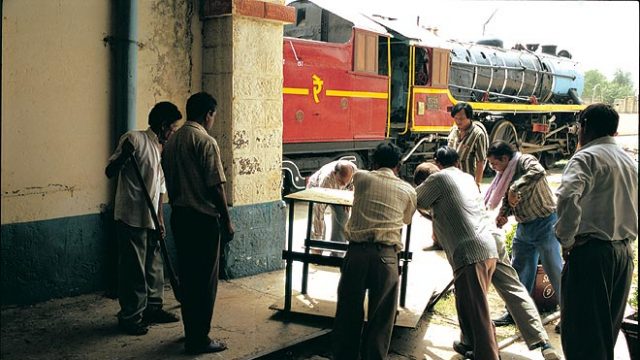

Section engineer Shyam Bihari, who runs the centre, needs very little encouragement to tell you who else likes having working steam engines around: it’s Bollywood. “Film producers use our engines, Gandhi, My Father (the upcoming Feroze Khan film), Gadar, Rang de Basanti (the next Aamir Khan release); they all used these engines.”

He lets us in on a little secret; no matter where the train scene in question is meant to be set, the bulk of Bollywood’s railway shots are done on a barely-used stretch of track near Bikaner. Of course, that’s a lot like the car chases in seventies films. These seemed to involve endless loops between Nariman Point and the Goregaon Film City, with little heed to the 30-kilometre gridlock in between. Still, the lonely track in Rajasthan is one of the few parts of the rail network where endless retakes will trouble no one but the film crew.

Keeping these steam beauties in running condition isn’t just a matter of contributing to the authenticity of a cinematic period piece, of course. Walking around the steam centre, I’m seized by an ineffable mix of loss and pleasure. Sadness because for me and anyone old enough to remember the age of steam, there’s a sense that rail travel has somehow lost a very fundamental sense of romance; pleasure because someone, somewhere believed it was important enough to disturb the long, long sleep of these kings of the railroad.

I’ve a good mind to disturb their sleep myself, so I walk over to engine 15005. It’s massive, but to the railways it’s a WLclass‘ light’ passenger engine, made many decades ago at the UK’s Vulcan foundry. This is another piece of railway history, which, in December 1995, ran the last scheduled broadgauge steam journey, on the Ferozepur-Jalandhar route.

Bihari and his crew are already posing in its cab form Madhu, who’s shooting them as they fiddle with its controls, and anyway a WL isn’t sufficiently testosterone-fuelled for this particular fantasy of mine.

What I’m looking for is just behind; it’s a 103-tonne WP, the big bullet-nosed steam locomotive reckoned by many fans as one of the best-looking engines ever to serve in India. These were based on a WWII-vintage design by America’s Baldwin Locomotives, but through the forties to the seventies, they ran nearly every one of India’s crack express and mail trains. So here I am next to a giant grate and firebox that must have looked like the gates of hell at full speed, feeling the hot loo blazing across the north Indian plains on my face, happier than I’ve been in years.

Didyoudoit? cries the lapwing. I did, I gloat.