One cool evening in May, my husband and I pushed through masses of Seoul citizens crowding the subway and made our way to the giant World Cup Stadium, which is to the east of our home in Korea’s capital.

Like hundreds of converging Korean fans, we wore our fuschia jerseys emblazoned with the tiger, the symbol of Korea’s national football team. And soon, like the 80,000 other spectators, we were on our feet, screaming as Korean mid-fielder Kim Do Heon scored a goal for Korea. We did the Mexican wave, we shouted “Dae han min guk (Republic of Korea).”

A woman plumped herself on the concrete steps beside us, cradling a toddler between her knees. She hugged him, then playfully tilted his head back as the child dropped his jaw in delight.

I imagined the upside down stadium as the boy might see it — grass-green sky, pin-sized angels in knee-high socks suspended from their cleats, kicking a gold ball which miraculously didn’t fall. A gunmetal spring sky on the floor of his world.

Or the story of how Korea crept through the door of my consciousness like a refugee cat.

“Game no good,” said Mr Kim our driver, the next morning. “No win.” Mr Kim had watched the game on TV the previous night, no doubt the evening lubricated with shots of soju. Senegal scored a goal in the second half making a draw.

We wore red plastic bracelets with “tu hong” embossed on it, Korean for “fighting” a sort of ubiquitous war cry for difficult obstacles. Often they say it in English, but there is no “f” sound in Korean, so that it comes “whiting.” Once, on a steep hike in North Korea, I passed a group of South Koreans going uphill.

“Whiting,” they chorused. “Whiting.”

I felt encouraged.

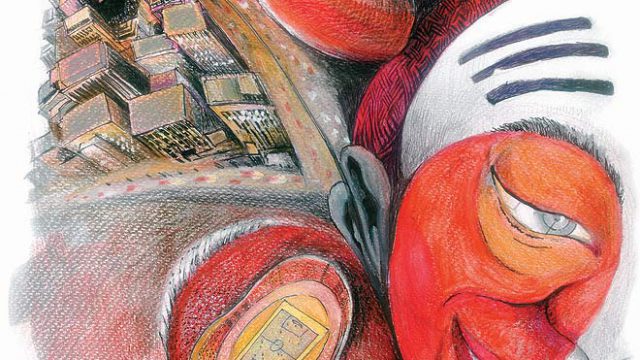

At the football stadium, the Red Devils, the official fan club of Korea’s national football team had booked the entire northern wing of the arena. They were a coordinated ocean of red jerseys, cheering to drums, jumping and waving in synchronised undulations. Some wore headbands with red horns that lit up with batteries, pinpoints of light in the deepening evening.

The crowd roared.

Businessmen had come straight from work, still in suits and ties, but they had pulled on the red jersey underneath. Shirts got untucked in the mayhem, toilet rolls flew across the stadium, unraveling white streamers. People wandered around cradling cups of Korea’s Hite beer.

In the middle, the Red Devils unrolled a vast flag and a hundred arms held it up and made it sway.

Squinting at the strong stadium lights, I thought how Koreans do everything in groups.

Sometimes, if the weather is nice, we head down to the banks of the broad Han River which traces a lazy “W” right through the city. There is a 40-km riverfront track for jogging or bicycling. It’s a pleasant spot, a narrow track divided and marked at each kilometre.

In the evenings the sun sets the water alight and sometimes egrets peck at fish in the shallower reaches. Often, a few men set up fishing rods, and then, if they’re lucky, tether the live fish to a ring and leave it in the water until they are ready to head to dinner.

We saunter down on weekends, avoiding the gangs of roller-bladers who whoosh past in total harmony in their shiny lycra outfits that hug each muscle, winged helmets like those of some obscure Central Asian god on wheels.

Tandem bikes, walking groups.

The individual here is powerless.

And yet, Koreans worship their heroes like anyone else. Park Ji-song, the country’s football champion, will play in a few days the last friendly match before Korea goes to the World Cup tournament in Germany. I’m eager to go to that game too, to suck in the madness of the crowd, the whorls of the cheering, the despair when a goal is missed.

The team is playing well, they dribble, they shoot, they pass to each other, two against one. They are professional and passionate all at the same time.

I find myself rooting for this strange, intense peninsula that has been my home for the past 16 months. I want them to win. When the game is over, the team gathers at the northern end of the field in a neat line. They put their arms around their shoulders and bow once, briefly, to their fan club.

And silently, in my mind, from a distance, I bow back.