In the afternoon sun, eddies and whirls on the flowing Bagda sparkle, framed by the bamboo-and-thatch roof of my balcony. I look left to a bend upriver, where the channel curls behind a little forest and disappears from view. Downriver and to my right, it plays hide and seek behind a copse of banana trees covered in creepers of luminous green. Across the channel, a tiny vehicle appears from behind a screen of thick leafage and floats across gleaming emerald fields to seemingly disappear, replaced by wild greenery and waving paddy. The road is so far away that I can’t see it, only the little toy car drifting across. Just in front is an embankment, with birds hopping, flitting and swooping in and out of the profuse undergrowth.

I see five varieties of birds in one afternoon, not counting the beautiful grey-green pigeon that sits on the bamboo rail of the balcony surveying me gravely, while I watch its brethren.

We left the highway from Kolkata behind at Kalinagar, turning right on to a semi-paved road which ran between eucalyptus trees. The sign on a gateless level crossing counselled people to watch out for the train, and the air grew cleaner and sweeter as we drove six kilometres into the interior of ancient rural Medinipur, to my destination. The eco-friendly Monchasha resort is located at Purba Medinipur, a new district of Bengal set in very old land. This area of the country has had continuous human habitation since about the 3rd century BC, or earlier. Tamluk (fifty kilometres away) is almost certainly the Tamralipti of the Puranas, or Tamralipta, named in the Mahabharata as a holy place. Ptolemy called it Tamalities, Huen Tsang called it Tan-moh-lih-ti(te).

For centuries, ships came from Bali, Java and the Far East to buy copper from this important river port. Much later, in the middle of the nineteenth century, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay went as deputy magistrate to investigate a robbery at close-by Contai (Kanthi to the locals, Cauntee to the colonisers), and was so struck by the scenic beauty and history of the place, that he set his novel, Kapalkundala, on that beach.

But that’s history, and very far away. Much closer, right in front of my balcony, is the river. The traffic on the Bagda is wooden boats, rowed by one boatman. They drift by, poling the water occasionally, but mostly drifting on the current, going the one way at this time of the day. It’s all enveloped in a haze of the delicious slow-down of being in rural Bengal—the voluptuous, luminescent greens, ponds and rivers, water flowers, dragonflies, ducks, thatched roofs, all moving in time to an older, slower world.

To my urban eye, this feels eerily like being in an etching by Haren Das, but in glorious Technicolor—the rambunctious near-neon of young paddy, the red of the earth parting the green for the path, the brooding dark olive of old trees under which it’s always dusk, the changing colours of the river—some reds and browns, but mostly a palette-defying cornucopia of shades of green, truly a land that nature owns and loves.

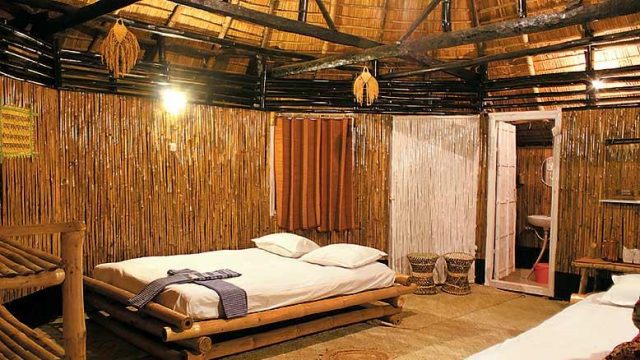

I wouldn’t come here if I was looking for a goal-oriented kind of holiday, wanting to see a number of places in a set time. Monchasha is a place more suited to slowing down and unwinding for a while. Debjani Basu, who runs the place with her husband Nilanjan, tells me that it is mostly a weekend getaway for those seeking to get out of Kolkata, and looking for an experience different from the usual planned holiday. “We wanted the place to be as unlike an urban environment as it is possible to imagine,” says Debjani. Standing on wooden stilts of local jhau (casuarina), the cottages are built entirely of bamboo, straw and hogla, which is a variety of wild water leaf that is both waterproof and heat insulating. “These are all materials that are traditionally used to keep structures safe in coastal areas that experience gale-level wind and rain,” says Debashish, Debjani’s brother, familiar with local mores. From inside the room, the eight-sided roof rises away in an inverted cone latticed with light-gold and black bamboo, making possibly one of the most interesting ceilings I have ever slept under.

There are four large rooms, each a cottage attached to another by a balcony. A room has two double beds, a bathroom and a balcony of halcyon delight. I don’t usually like mosquito nets, but the large beds, and the roomy, rose-tinted netting was comforting in an old-fashioned way. I was also apprehensive about the bathroom facilities in the context of rural and eco-friendly, but the bathroom turned out to have all the mod cons, including a tiled floor, surrounded by walls of bamboo and a roof of straw. The walls and ceilings of the eight-sided room are made entirely of bamboo, and the floor is flexible and somewhat bouncy.

“Kids from the city like it here,” says Debjani, and I can see why. There’s unlimited mud, grass houses on stilts with bouncy floors, lots of space to play, fishing and boat rides for everybody. On the river is a down-sloping little jetty that I negotiate with slowly increasing confidence, to the black-, white- and- red boat bobbing prettily while I try to step in. “It’s about balance,” says Jadab-da, boatman and storyteller, “you sit in the middle as you want to, and I’ll balance from this end.” He tells me of the rhythms of jowar and bhata—the rise and fall of the river with the tides of the sea. “The water is high at jowar, and you can take a boat out without worry. Larger rivers don’t have this problem, but our Bagda during bhata is not good for a boat.” I saw the exposed mudflats at low tide, and can understand why a boatman would be wary of them. He scorns gently my delight at being out on the river. “This is nothing at all,” he says, “It is purnima nights that are really beautiful. Sometimes when I am out on the river in full moon, I forget that I live here and have seen this all my life.”

That evening, I went to the haat. Paushi’s haat sits on Thursday and Sunday. On Sunday, I found the market abuzz, with the sort of glowing produce found only in rural markets. Lal saag, coconut and paan are local specialities, but the karela was quite spectacular, and served in a light shukto (mixed vegetable curry) the next day, tasted every bit as good. I walked around the corner to the fish market, and saw the produce of the river that flowed by my balcony. “So close to the sea,” Jadab-da had told me, “Paushi’s Bagda is saline all year except during the monsoon, when it is sweet.” This riverine environment is friendly to fish and prawn, yielding tangra, bhetki, boal, parshe and bagda as well as golda chingri to the nets that are spread by villagers along the channel banks.

I’ve always found that food tastes better outside the city. While the fare is not particularly light at Monchasha, it tastes very good, in keeping with eating and rest being the two stated goals of the place. I had luchi and a white potato sabji for breakfast and liked it very much. Other food that I enjoyed over my two-day stay is the malaikari (a prawn and coconut curry), the shukto, the lau-bori (sweet gourd with dried dal cakes) and the mustard fish. All of this is served on traditional Bengali kaansha, or brass crockery, tattooed with ‘Monchasha’ in Bangla. A spicy paan grows locally, which Chandana at the haat folded with zarda and supari. It packed quite a punch when I had it after dinner, and sent me tottering down the garden path to bed.

On the second day, I meet Nirmal Bera and his family, who are potters in an adjoining village. They are working overtime to complete orders for Durga Puja, and their courtyard is full of perfect clay pots of various shapes and sizes, waiting to be baked. Nirmal’s father tells me that although the Beras have been potters for generations, the advent of plastic has rendered this form of livelihood unstable, and their traditionally successful products are no longer as much in demand. As there are unfortunately no smaller fired pots available at the moment, I am unable to buy any.

From there, I travel to the Sarpai Sarbamangala mandir (4km), whose idol is so old that the Kali is only a block of stone, covered with sindur and set with arresting metallic eyes. “The old temple is gone, but the idol remains and the ghat leading to the pond has some ancient stones that have shakti,” says Kajol-di, who opens the temple for us. “Ma Mongolchandi is about 200 years old, and very jagroto (powerful) in these parts.” Reached over a rickety footbridge, and set in a clearing beside a pond and a huge dark banyan tree, the temple reminds me that this area of Bengal has been a home of Tantra for several centuries.

My legs dangling over the side of Kanai-da’s van rickshaw, I pass through red-earth lanes in a leisurely motion, drifting by peaceful scenes of rural Bengal. Kanai-da, van rickshaw driver and local guide, answers occasional questions or passes on information as we move around. Since this is a village, and everybody knows everybody, there is some friendly curiosity about who I am and where I’m going. I’m on my way to Kanai Bhoumik’s house (2km), to see his work with bamboo, and then on to Monotosh Maity’s (2km), to see his work with coconut shell. I come back from this trip with a little boat made of bamboo and coconut, which is almost a replica of the one parked beside the jetty behind my cottage.

But the highlight of my visit arrived that the evening. Five Vaishnavite men came to Monchasha and, sitting on the mud and cow-dung portico, sang kirtans of devotion and philosophy, love and loss, by lantern light for almost two hours. The evening darkened, and it became quieter and completely still all around. Cool night breezes blew off the river, ruffling the flames of the lanterns. But they played dholak and harmonium and sang on enraptured, more for their own pleasure, seemingly, than for an audience. It is difficult to describe in words the musicians, the songs or the ambience, but when I go to Paushi again, I will certainly ask Jadab-da if he could please request them to come and sing for me again.

The information

Getting there:

Monchasha is located in Paushi village, Purba Medinipur, about 130km from Kolkata.

By car Once out of Kolkata, turn left on to NH6 (Dankuni-Kharagpur tollway), then left on to NH41. Turn right at the Kalinagar Kali temple. 6kms of pastoral road takes you to Monchasha (140km approx.).

By bus Buses that run between Kolkata and Digha can drop you at Kalinagar. Golpark is where the AC buses (Rs 350) leave from; non-AC buses (Rs 100) start from Esplanade or Garia. Monchasha provides transfers from Kalinagar bus stop (Rs 300).

By train The Tamralipta Express and the Kandari Express go daily from Howrah Station (Kolkata) to Kanthi (Contai; Rs 250, chair car). Monchasha offers station transfers (Rs 650).

Getting around:

Walking or van rickshaw (Kanai Pal/Rs 200 per hour) are the best ways to get around, while the boat is the way to see the river (Jadab or Madan Laya/Rs 200 per hour). Cars can be booked to go further, like the Digha beach (50km), Mandarmoni (47km), Tamluk (50km), the Bahiri temple (24km) or Contai (23 km).

The property:

There are four cottages, each with two double beds (Rs 3,000 per cottage, Rs 500 for an extra adult, free stay for kids below 10; 9830203973, monchasha.com). All meals come for an extra Rs 585 per head per day. If you’re going with a driver, they can arrange accommodation and meals (Rs 300 per day).

What to see & do:

The time to visit is winter, when the liquid nolen gur is made fresh from the khejur plant, and goyna-bori with posto (poppy seeds) are available. The Patachitrakar community of Nandigram is a must-visit, if they are around. Patachitra painting with storytelling, puppet shows and pottery demonstrations can also be organised on request.