“As you never may find the forest if you ignore the tree, so He may never be found in abstractions.”

– Kabir

Inspiration can come in many forms: well-crafted poems, beautiful trees, isolated islands, scenic rivers, dear friends, surprising encounters. Still, it’s unlikely you’d find inspiration in a toothbrush. But then again, you’ve probably never seen a toothbrush like Kabir’s.

I found my own inspiration upon my first sighting of this famous toothbrush, waist deep in the muddy water of the Narmada river. Kabir’s Banyan must indeed be the most spectacular toothbrush in the world. It began life as a toothbrush some 550 years ago. Kabir, the great sage and poet, was on an island near the mouth of the holy Narmada, cleaning his teeth with a meswak twig. When he tossed away this toothbrush, goes the myth, it sprouted into a giant banyan stretching a hundred metres across. His poetry continues on as an essential part of Sikhism, and ties together Muslim and Hindu thought. His wisdom continues on as a key part of Indian mystical knowledge. His toothbrush continues on as a natural wonder of the world.

I had arrived from Mumbai in the Gujarati city of Bharuch, next to the Narmada. I knew that the river started high in canyons among Central India’s sandstone mountains, but here in the lowlands it was a lush and fertile valley. Bharuch has been an important seaport since ancient times, known to navigators throughout the Old World. It is hard to find much evidence to remind you of the daring sails that ventured across the seas of long lost days. It’s also hard to imagine earlier days, when crossing the street among the ocean of trucks, two-wheelers, cars and autos wasn’t such a challenging endeavour. I escaped Bharuch as soon as I could, but not before tasting the regional snack-food speciality — roasted peanuts available from vendors on the street.

A fast bus ride from Bharuch on good roads took me up the Narmada river. Arriving at a small cluster of tea shops, where I bought an apple, I joined other pilgrims for the boat ride across the river. There was a catch, however. The tide was out, the river was low and the boat couldn’t reach the docks on the island. We had to hop out of the boat into the river — mobile phones and cameras held aloft — and together squelch through the mud of the sacred river to the steep banks of the sand island. The captain of the boat watched our antics with a bemused smile.

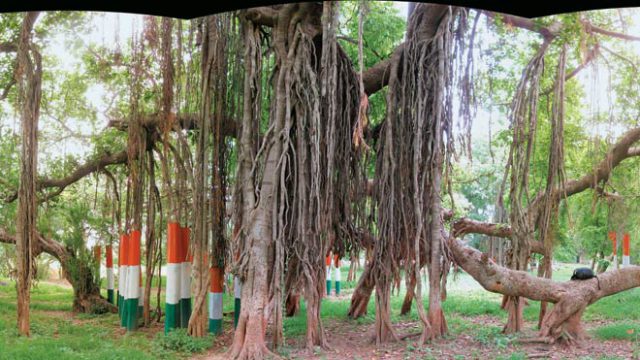

From the beach, my fellow pilgrims and I followed a path directly under an entrance arch into a forest grove thick with stems. But something was uncommon about these trees. They were all twisted together at the top, linked in a strangely unpredictable way. The entire grove was a single living thing, a giant toothbrush and a botanical wonder combined. There is something curiously abstract about giant banyans, sandy islands and muddy rivers. All are flowing objects, solid in concept but fluid in form. I had seen some of the other giant banyans — Bangalore’s Dodda Alada Marra, Chennai’s Theosophical Society banyan and Calcutta’s famous Botanical Gardens tree — but this one is special: it’s the only one living in the middle of a river. Standing on this large sandy island, I could imagine the roots of the banyan tree holding all the river sand and mud together from drifting out to the ocean.

Inside there were tangible reminders of the modern world — a temple newly built in a clearing hacked from the tree, snack vendors, tourists babbling on mobile phones — but these were easily forgotten as I wandered into the corners. Near a lingam shrine at the entrance, I bought some biscuits. The langurs watched me intently, but realised quickly that I wasn’t going to feed them any. It’s ironic that these monkeys would be eating tooth-rotting food given by pilgrims to a giant toothbrush. The environment inside was a novel lesson in nature’s ability as an architect. What makes the banyan tree so special is its amazing ability to reconnect itself with the earth. From the large branches arching overhead, aerial roots hung down in rope-like clusters. Some were being guided to the ground in metal cages, trained to form a future stem. Outside the tree’s canopy, bright sunshine rained down on farm fields, but it wasn’t hard to imagine that the tree would just keep growing and one day swallow the entire island.

Unfortunately, modern threats to this ancient tree have been acknowledged. Changing rainfall patterns, rising oceans and hydroelectric projects can all alter the flow of the Narmada dramatically. Sand in a river is a shifting thing, and an island of sand is a chance occurrence of currents and topography. Any changes to the river’s water flow and the sand island could quickly erode into the sea.

The other visitors to the tree were delighted at the atmosphere of the place. There were both religious pilgrims and nature-oriented tourists. We felt a special kinship in being on the island together, and the busy cities seemed a distant memory. As we walked on the beach back to the mud, a friendly family offered me yet another snack — a delicious banana. We waded into the holy Narmada, clambered onto the boat and returned to the rest of the world. We had emerged from the wonderful shady embrace of the toothbrush to the bright midday excitement of modern-day India. Waiting for the bus back to Bharuch, I paid my own personal respect to Kabir’s memory. I had been snacking all day. I dug in my bag and found my modern high-tech toothbrush and neem-meswak toothpaste.

The region is well connected with the roads and rail networks at Bharuch, Gujarat. You can easily access the town by heading on a northbound intercity train from Mumbai, or southbound from Ahmedabad. From the city, you can catch an eastbound bus 16km to the northeast to the ferry landing. However, if the tide is low you may have to wade through the water to get there.