We are outside Aberdeen railway station at 9 o’clock on a brisk, late August morning. I have taken the overnight sleeper from Euston station in London, and Dan has come in from Edinburgh where he has been partying with friends performing in the festival Fringe. We have greeted each other with cries of joy: “God, man, you look like something the cat didn’t want to bring in. Didn’t you sleep in Edinburgh?” and “Hey Joshi, you hit a distillery already last night?” We both look hung-over even before the great Booze-tirth Yatra has begun. And now both of us retch at the sight of a crowded pub at a time when it is early, even for a pair of hardened drinkers like us.

We grab an antidotal ‘Full English’ at the café next to the pub, a ‘Full English’ being the mother of all killer-cholesterol breakfasts: toast, fried eggs, baked beans, bacon, sausages, potatoes of indeterminate denomination, coffee-water and a glass of thinned yellow paint. We pay the bill and get out. The man from the car-hire company pulls up, we put our bags in the boot and drive to the garage.

“Can we please have a Beamer?” Dan says hopefully. “Och, we dun’t do BMW. But let’s see what they’ve orrdered forr you…ah.. it’s a new Nissan and nae a wee one, it’s a saloon.” We look at the new Nissan. “That’s a guzzler,” points out Dan, looking at me meaningfully. I take the cue. “Can we have something smaller?” I ask. I almost say “something wee-er” but stop myself.

Shortly, we find ourselves on the A96 highway, heading westwards, and, in a few minutes, the tiny Aberdeen hinterland is wiped from memory. We are now driving through bumpy land covered with tufts of heather which, I note to my surprise, actually is purple. The flatland changes to gently rolling hills, and the unpatriotic Dan winds the car through, swaying happily to the sound of the Australian steamroller flattening anything remotely English at the Oval. After about an hour’s drive we arrive at the town of Keith.

“Keith?” I mutter, “What kind of a name for a town is that? Next they’ll have one called Dan.” “Or Shane or, indeed, Glenn,” agrees Dan, caressing the steering wheel and tricking the car off the road and in through the distillery gates.

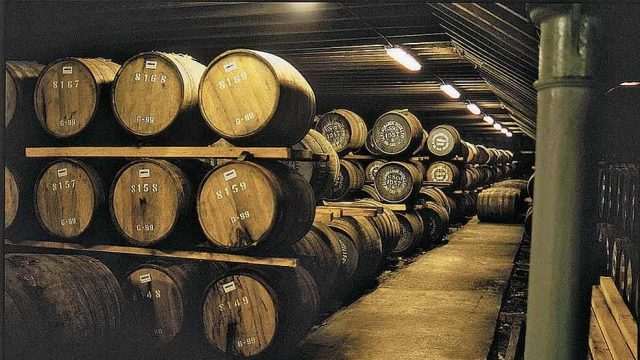

The Strathisla distillery (pronounced Straath-aila as in ‘Aila re aila! Daaru-cha karkhana aila!’) is the first on our itinerary. It is, we are told, ‘the home of Chivas Regal’, and sure enough the first thing we see is a huge tanker with the Chivas logo painted on the side. I’ve always known that whisky-making is a huge, huge, industry but seeing the tanker gives me a jolt nevertheless. There is still a part of me that is expecting tiny, windswept, buildings perched atop craggy rocks, with dour old Scotsmen coming in and out, fighting through blizzards, stumbling under the weight of loaded oak barrels, pipes clutched dourly between their craggy, windswept teeth.

We find Yvonne Thackeray, a young woman who is about as un-craggy and un-dour as you can get. She leads us into the reception area of the distillery and gives us coffee and shortbread biscuits, after which she takes us on the first of our distillery tours. Across the next three days, with a few variations, we will follow more or less the same journey of the barley from field to bottle.

As we walk through from mash tuns to still house there is an odd sense, both of an old world preserved as well as a very clean, modern, mechanised, small, production plant. Things seem to happen on their own: yeast rises in vats, clear spirit pours through tubes in glistening brass cages called still safes, the big copper stills give off heat and tiny leaks of nascent whisky from the rivet lines. Occasionally you see a man doing something, fiddling with meters, going through a ledger, peering into a vat, but nothing dramatic and nothing strenuous. The whole distillery (admittedly one of the smallest ones operational) is run by, perhaps, seven or eight people — it almost seems as if the whisky is making itself.

Within 45 minutes Yvonne brings Dan and me to within striking distance of the pot of gold at the end of the process rainbow — the tasting room. Different distilleries have different ways of letting you sample their product. Some include the price of a dram in the ticket for the tour, some others are more generous and let you have a couple of drams free, others have pretty young women with trays loaded with teeny glasses and they play it by ear, letting you have more if you look like you’re going to be a big spender at the distillery shop. At Strathisla, Yvonne leads us through the whole process, letting us sniff and taste from a row of glasses, from grain whisky to un-matured malt to one aged five years to ten to a blended whisky, which was, of course, Chivas, which uses the Strathisla single malt as its ‘spine’. We are also given a taste of one single malt from each of the different malt-producing regions, again, with the 12-year-old Strathisla representing the example of the region we are in, which is Speyside.

It is only when we leave Keith and hit the A95, when the road signs begin to pop up, that I realise the concentration of famous whisky names in Speyside. Again, not being a deep homework kind of guy, I had always imagined the distilleries very far away from each other. But now here we are, zipping past signs for Aberlour, Knockando, Balvenie, Craigellachie, Glenlivet, all of them, it seems, within minutes of each other.

Soon we reach Dufftown, which is roughly at the centre of the Speyside distillery cluster. The town obviously survives on whisky and its spinoffs. We grab a quick lunch and duck into a handicrafts cum bookshop. I open a couple of books and do a quick flick-through. Whisky tasting, I know, is as arcane and bottomless a hobby as wine-tasting. Among the usual stuff about a certain whisky having hints of ‘heather’ and ‘apple’ and ‘seaweed’, one of the tasting notes I have read insisted that an Islay malt had an “undertone of an East German dentist’s chamber”. I put down the books and decide to depend on my own nose. I buy a cheaper bottle of single malt, called Old Fettercairn, to counter any distillerarious parsimony we might encounter, and we head off from Dufftown and vaguely towards the fountainhead of one of my favourites, the Macallan.

The land is not craggy but gently hilly, and all around us are late summer flowers and fields of golden barley. We happily lose ourselves at the Spey river and then find our way again. By the time we pull up into the Macallan parking lot, the distillery is shut. We look around at the signs, take a deep breath, in case there is a leaky cask somewhere, and drive off again, dipping judiciously into the Old Fettercairn. We decide it’s been a full day, and what we want to do is take a look at the ruins of an old bootlegger’s shed on the Glenlivet Estate and then head for the poshest hotel we are going to hit on this trip.

Minmore House is, as the pamphlet says, “an elegant country house standing amid the magnificent scenery of Glenlivet Crown Estate…”. Dan whistles as we pull up on the gravel outside the house. Lynne Janssen greets us and sends a young German staff to show us to our rooms. Each room in the hotel is named after a single malt. Mine is the Glenmorangie, which is another favourite.

Downstairs, the bar is full of foreigners who have been hunting, shooting and fishing. Dan and I make our way through the orders for red wine and Campari, and look at the real stuff. We settle down with our drams and wait for dinner. On the wall I notice old reviews from newspapers and I go up and start reading. It seems Lynne’s husband Victor was a renowned chef in apartheid-time Durban, where he ran his own French restaurant. Later, Lynne tells me that they gave the new South Africa a chance but that after a while it got too much. A few years ago they put up sticks and pitched up here in Lynne’s home country.

New or old, Sutth Efrika is much in evidence at dinner. The wine we have ordered is from the Cape, as is the young woman who serves it. She is tall, blonde, and her accent is veyri South African-wealthy-girl-working-on-her-holiday. “Great,” I say after I taste the wine. Dan takes a swig too and grins at her. “It faan,” he says, putting on a Cape Town accent which will not go till four days after we geyt bek to London. “You laak it hey?” says the woman and briskly goes off to get our food.

Victor Janssen’s food is a kind of cuisine preserved from the post-war years when French food was becoming popular in the Anglo-Saxon world. The first course is snails served in a prawn sauce; then comes a beautifully cooked piece of Scotch beef, unfortunately smothered in a thick, Bearnaise sauce; followed by a crême brûlée which is Janssen’s signature dessert.

The breakfast at Minmore is a more sophisticated version of the previous day’s Big English, and Lynne, who is a kind woman, calls the Glenmorangie distillery and makes sure it is open on a Sunday. We make our way north, through Inverness to the town of Tain, near which Glenmorangie sits. Having mash-tunned and stilled and sampled there, we have made our way to the beach at Dornoch, a few miles north. We have sat there, so close to the northernmost point of the British Isles (150km) yet unfreezing, and watched the North Sea do its thing. With our lungs full of briny air we have driven back to Inverness and reality. Suddenly, we are drinking Cobra beer and the Marathi computer engineers on the table behind us are ordering their stuff. One says, “Bacardi and Coke please.” His friend is ambitious, “Long Island Iced Tea? You have?” And then a completely vegetarian food order, to which I feel like shouting, “Meat! Eat meat! The vegetables are from 1976!”

The next day we get out as fast as we can. We have a long drive ahead of us to reach the other side of Scotland — the island of Skye. On the way there is the arduous stop at Glen Ord distillery, made pleasant by complimentary T-shirts with the distillery logo and two medium bottles of their product — the only free bottles we get on the trip. As we start westwards, Dan drives beautifully and gracefully, saying nothing about the fact that I am drinking his free bottle of Glen Ord first. A quiet and ruthless young man, he exacts his revenge in the late afternoon by making me go on a walk up a hill near a very inviting pub and restaurant on the highway.

We squelch up the hill, Dan leading, as a trained and seasoned rock-climber should, and me hyperventilating behind. After a half hour we stop. I look down into the valley and realise with a stab of fear that I can no longer see the pub. “Good, eh?” says Dan, filling his trained chest with Scottish mountain air. “Good,” I gasp, “very good. Now, can we go back?”

“Ach, thet wuss greyt. Really lekker,” says Dan, returning to the pub an hour later. I lick my wounds and do a solid job with my steak and ale pudding. It’s a good and clever thing to do, to eat here at The Cluanie Inn on the A87, because Dornie on the Kyle of Lochalsh, where we are headed, is a tiny seaside town with nothing of consequence open after six o’clock in the evening. We do a post-prandial drive and within an hour we arrive at the Tigh Tasgaidh B&B at Dornie. It is about ten at night when we reach and, silhouetted against the fading light, we can see the Cuillins, the steep mountains on the magical island of Skye which we will drive to the next day.

The next morning the island is much clearer through the windows of the breakfast room at the B&B. We drive up to the Skye Bridge, which is yet another marvel of British engineering — a huge span that connects the mainland to the island. As with all modern technology, there is a price to be paid. The toll at the bridge is extortionate. As we drive across, high up above the swollen sea, the sky decides to demonstrate why this island is named after it. The grey clouds deepen and join hands with the steep mountainside, as if to say, “Let me show you, laddie, what real environment is.” A fine rain begins to lay its net over our car. Dan has been complaining over the last three days that this sunny weather is an undeservedly soft Scottish welcome for me, and the rain and the wind flexing against the light suspension of the car makes him grunt with satisfaction.

“There are about 400 discernible flavours in whisky. Of these, we can control about seven,” the manager of Talisker distillery Alastair Robertson tells us, generously pouring us another shot of the best whisky we have tasted on the trip — the Talisker’s 17-year-old cask strength. Outside, the rain drums down hard on the sloping roofs of the plant. I take a sip from the glass and I fancy I can discern a few of the flavours — sea air, kelp, cinnamon, burnt toffee, and, perhaps only on my tongue, a fine tympani of Alphonso mangoes. “Go on,” says Alastair, “I can see you like it. I’m sure I can give you one more.” He has the quiet look of satisfaction that artists get when you respond to their work in the way they want. I know there are two days left to the trip, I know there will be more beautiful landscapes and, probably, other distilleries too, but, suddenly, I am not that concerned. I look at the rain lashing at the window panes. I look at the glass in my hand. I look up and my eyes meet Dan’s. The jokes and cynicism have been put on a seat far at the back of the car. I can see that we are both taken. Definitely Hapoos mangoes, no doubt about it, and the possibility that something good exists outside our understanding now definitely much increased.

I raise my glass to Skye and take another full gulp.