The Thunchan Festival in Kerala: an annual gathering of writers and scholars from all over India, held in honour of Thunchathu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan, a great 16th-century poet, who rendered the two great epics into a Malayalam that made them accessible to the common people. M.T. Vasudevan Nair, the Malayalam writer and Jnanpith winner, who invites me to the Festival, tells me that Tirur, where the Thunchan Memorial Centre is situated, is about four hours drive from Cochin. My friend Gita Krishnankutty receives me at the airport, a spanking new building with impeccable aesthetics, and takes me to her ancestral home in Chengamanad. As always in Kerala, I’m amazed by the idea of this being a village; such a contrast to the villages I’ve seen in North Karnataka, poverty stricken places with crumbling mud and stone houses. Gita’s ancestral house is not my idea of a village home, either, and her mother, a translator like her daughter, is equally unusual. The lunch, however, is typical Kerala – jackfruit, banana, brown rice, avial. The jackfruit dish is delicious. I ask for the recipe. “Pluck a jackfruit of just this size…” Usha, my hostess, says, pointing to the tree outside. I give up the idea.

On our way to Tirur, Gita suggests we visit Guruvayoor. We are lucky, the crowd is not too large today. We are told we can have a darshan in fifteen minutes. While we wait, Gita tells me how, as children, they helped to light the oil lamps in the niches in the wall. It looks beautiful, she says, when they are all lit in the evenings. The idea of letting children participate seems equally wonderful to me. Soon the idol is brought out and the crowd, which has been exclaiming in delight over the richly caparisoned baby elephant, on which the idol will be mounted, immediately prostrates itself reverentially – with such unison, that it is like the wind passing over a field of wheat. The elephant, with a sedateness belying its youth, takes the idol thrice round the inner sanctum, unperturbed, it seems, by the music that precedes it. Then we are let in – women first. The urge to stand before the idol has to be curbed, people behind are impatient. The priests keep urging us to move on, not harshly, but with a gentle “you can always come back. He’ll still be here”. It is Gita who translates this for me, giving me a sense of the courtesy in the language.

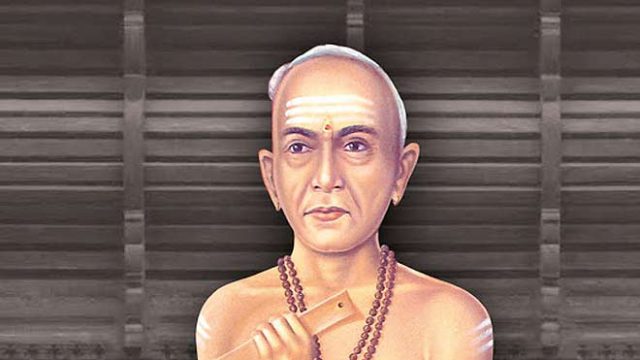

The next morning, we wake up in Tirur to the fanfare of pipes and the rhythm of drums. Music that quickens one’s heartbeats. There is excitement in the air, people are gathering for the procession. This is not a religious procession; the utsav murti here is an iron stylus. The same one, it is said, which was used by the poet for his writing. Only a legend, maybe, but the devotion and solemnity on faces spells out total belief. It’s a picture postcard scene – women and girls in the typical Kerala gold and white, their hair loose, trays of flowers and lamps in hands. An umbrella is held above the stylus, as if it is truly an idol. Writers and scholars join the procession, but the Tamil poet Kanimozhi runs about energetically trying to get pictures. When the procession returns, there is a ceremony in which the various writers speak briefly in their own languages. I hear Marathi, Gujerati, Hindi, Kannada, Tamil, Konkani, Malayalam. This too is a tradition, I’m told; a newly evolved one, but attaining the same sanctity as the old ones.

After this is the National Seminar, in which writers speak of the nation and the writer. All seminars and conferences have a sameness about them; so too this one. What is remarkable here, however, is the audience – a large audience, everyone, young as well as old, listen with an untiring attentiveness. My admiration for the audience is reinforced when I see them, the next day, listening patiently to a seminar on education, even though it is well past lunchtime. The speakers too go on with undiminished gusto, but a young man, sitting outside under the trees like us, grumbles, “No one is speaking of the pay scales!” I am reminded that this is Communist country. The simplicity and austerity that proclaims itself everywhere tells me how and why Communism could get a foothold in here. The meals, as simple as the people’s clothes, are cooked and served by volunteers from the town. They stand about, chat, urge guests to eat and even bravely try out their Hindi on outsiders! It’s vegetarian food, something, we are told, that’s hard to get elsewhere in town. This is North Malabar, with a large Muslim population. Tirur is next door to Calicut, the place where Vasco da Gama first landed and was astounded, both by the opulence of the place, as well as the number of Arab traders. Gita tells me that the word for bazaar here is ‘souk’, a word which comes from that past. Fascinating how language can evoke history.

We wake up the next morning to the sonorous chanting of the poet’s Ramayana in a male voice. I see the man later, sitting alone in the large hall, an oil lamp glowing in the semi-darkness; he is chanting from memory. We have time to go round the Centre today. There is a small temple under a tree, the same tree, legend goes, under which the poet sat. A Nux Vomica tree, but the leaves of this tree are, it is said, not bitter. Even more pleasing than this legend, however, is the information that no rituals are performed in this temple, for to do so would be to bar non-Hindus and lower castes from it. I’m equally impressed when I’m told that parents, of all castes and religions, flock with their children to this place on Vijayadasami day. Here, in the Saraswati mandapam, the children learn their first letters. What is just as amazing is that writers come from all over Kerala to guide the children in writing their first letters. A remarkable knitting of literature into the lives of the people. And unique, surely?

All the days I’m there, crowds continue to stream into the Centre. It’s a combination of tourist place, place of pilgrimage, as well as an educational outing. Hordes of children pour in and walk in an orderly single file through the place. Once they have done with the tour, the teachers relax and have coffee and snacks at the all-women run canteen, while the children chat, giggle and stare at the visitors. Gita and I are the uneasy victims of this unrelenting curiosity. When Gita speaks to them in Malayalam, she is let off. I’m the stranger now; they turn to me and, laughing at their own daring in speaking English, ask, “What is your name? How do you do?” With this, their stock of English is exhausted. Conversation peters out. We enjoy their company, nevertheless. Headscarves, sandalwood and kumkum on foreheads and crosses round necks spell out the different communities. Yet essentially they are all alike in their bright inquisitiveness, their delight in speaking to strangers. They are bolder than the boys who hang back, until a group approaches, shamed, perhaps, by the girls’ boldness.

If we attract curiosity, MT, as he is popularly known, attracts awe. I can see he is a legend to the people here. A crowd collects round him. He ignores them at first, then turns round and confronts them, almost, it seems in desperation. For a moment they stare at each other in silence. Finally he begins to talk. The questions come thick and fast. “They all want to know about Leela,” he says, explaining that Leela is a character in a story of his. I’m again amazed by the way literature is a part of people’s lives. I see this again in the writer-reader interaction, during which writers and questioners sit in a circle, an outer ring being formed by a large audience who listen raptly. The moderator translates questions and answers into Malayalam for them. He seems to be a skilful translator; the whole-hearted audience response spells this out. Schoolchildren, too young to understand, listen in respectful silence. And when, after a while, the teacher beckons, they get up and walk away noiselessly, careful not to disturb the gathering.

In the evening we go to the Thirunavaya temple nearby. It’s a Vishnu temple, the idol being called Nava Mukundan. Why ‘Nava’? The priest has no answer. An older priest, relaxing after the morning’s puja, legs stretched before him, his face as spotless and gleaming as the puja vessels, which have been scrubbed and placed to dry in the sun, shakes his head too. The idol is on a height, scarcely visible to worshippers. The Devi, however, is closer, at a lower level. I get echoes of past lives, of distant fathers and intimate accessible mothers. Across the river, which runs by the temple, are two more temples of Brahma and Shiva. “Can you see them?” an old priest asks, adding mischievously, “You need young eyes to see them.” It’s peaceful, sitting on the steps leading to the river. Nearby a family goes on with its rituals. Funeral rituals I gather; the river carries away the offerings like it does everything else and upturned pots bob on the surface. This, the Bharata, is the longest river in Kerala, Gita tells me; but now, due to relentless dredging of the sand, a shadow of its old self.

On my way back to the airport, my companion, a poet-bureaucrat, speaks of poets and poetry, of how poems are sung or recited and the cassettes played by taxis on their long journeys. The river seems to be travelling along with us, disappearing at times, but invariably returning to give us company. The car often slows down, at times it stops; something is holding up the traffic. When we move on, we find that the hold up was due to an elephant. We see them marching with a majestic dignity by the roadside, a branch or a banana stem in their mouths – their snacks for the journey, obviously. This is festival time, I’m told and the elephants are moving from temple to temple. In a while, I get used to them; there’s no longer any surprise at seeing them. But my delight in their serenely majestic presence never fades.

Communists, temples, elephants, rivers, writers, poets and legends – all woven together into a complex fabric. And yet the question I’ve not been able to ask anyone remains: why, for God’s sake, do they call it God’s own country?