Dharansi. A hanging valley. I savour those two words. What a delicious idea! I close my eyes and try to remember if I’ve seen one before. There was that small hanging plateau on the northern marches of the Indrahar pass in the Dhauladhar. But this was massive. I was sitting in the middle of a large smooth bowl, covered in turf and little splashes of tiny alpine flowers. Running through the grassy side were long, shallow gullies, filled with the rubble of boulders — the giant moraines of winter snowfields. Right in the middle of the bowl, where our camp was pitched, lay the longest and widest of the moraines. It was also the lowest point in the curve of the valley, almost a hollow. It continued for a little way below the tent. Then, from a cutoff, the valley dropped a couple of hundred feet into another bowl, less wide, more hemmed in by serrated cliffs. The valley then wound down gradually, like a lazily flowing river, then it suddenly ended, as if someone had sliced it off with a very large knife. A tortured, broken precipice plunged dramatically for 5,000ft into the spectacular gorge of the Rishi Ganga. The Bhotias believe that demons live here, and none but holy men may pass through. Thus the river gets its name.

It was up this gorge, in 1934, that two English mountaineers and three of the greatest Sherpas of the day forced the only — and till then uncharted — passage into one of the most unique mountain fastnesses in the world. Eric Shipton and Bill Tilman’s adventure was an improbable one, one of the last heroic journeys into the unknown. Shipton’s elegantly romantic book, Nanda Devi, had warmed my heart for many years. Here at Dharansi, the furthest I could get into Nanda’s secret garden after days of incessant rain, landslides and storms, I could hardly believe my luck.

I’ve always been big on hidden paradises. Right from the lonely little lake in a mango grove in my native Bihar where I spent many solitary afternoons to Dung Lung Dor and Oz; I wanted to see them all, if only a glimpse. These places had their rules. It would have to be a perilous realm; you’d endure many hardships trying to get there; and you could never hope to reach without a large helping of grace. Over the years I’d been to some unimaginably lovely places, and lonely places, but I had yet to see a place like Dharansi.

Above me, the bugyal stretched upwards at a gentle incline. Directly above the rim of the bowl lurked Hanuman, a prickly black mass of heavily compacted rocks, leering down at me like a nightmare fortress. A modest 19,931ft high, it is best known as one of the standard climbing peaks for trainee mountaineers. But the mountain has a local reputation that is somewhat more sinister. The villagers of the Niti valley, especially those of Dunagiri village, don’t take too kindly to the monkey god. In fact, many despise him, and consider him a thief. When Hanuman flew to the Himalaya to find the magic herb that would cure Lakshman, this is where he is said to have come. Not knowing which the correct herb was, Hanuman hedged his bets and made off with an entire mountain.

A little way up the slope, a herd of bharal, the famous Himalayan blue sheep, stood watching us. There were nine individuals. Three sprightly youngsters pranced about unsurely on the massed jumble of boulders. Three ewes, their long black eyes watchful, were licking salt off a large table-shaped boulder. One of them had a single short horn, making her look uncannily like a unicorn. Last of all were the three rams, aloof and sporting impressive curving horns, extremely skittish and keeping their distance. When Shipton and Tilman had broken through to the inner sanctuary, they had been pleasantly surprised to find large herds of bharal grazing on the meadows of the sanctuary, absolutely unperturbed by their presence. That was seventy-eight years ago. By the time all entry into the sanctuary was banned in 1982, the widespread hunting of these beautiful animals to provide meat for mountaineering expeditions had resulted in a near wipe-out. That had also affected the bharal’s chief predator, the snow leopard. I’m sure there was one around, but of course I’d never be able to see this Himalayan ghost unless he wished to be seen.

I had met another such famously shy animal a couple of days ago on the upper slopes of the meadow of Lata Kharak. I’d gone walking to the adjoining ridge of Saini Kharak to get my first glimpse of the legendary Rishi gorge and, if lucky, Nanda herself. We were traversing the cliffs of the junction of these two ridges when Raghubir Singh, one of our porters, clutched my jacket and pointed to a massive rock face and said “Kasturi!” I had to focus before I could make out the distinct brown shape of the musk deer, surprisingly close, looking at us with some alarm, twitching his black nose. It looked like a cross between a deer and a kangaroo, the startling feature being the animal’s vampiric canines. In a few seconds he was off, bounding straight down the sheer cliffs with dizzying speed.

Raghubir Singh of Lata is a legend from a legendary village rife with legends. He and his friend Dhan Singh Rana, my guide Narendra’s father, were highly feted high-altitude guides and porters during the heyday of mountaineering in the sanctuary in the 1970s. Even earlier, from the time Shipton first came to Nanda Devi, the people of Lata have featured prominently in the history of mountaineering in this area. The villagers of Lata are Bhotias, like the rest of the denizens of the Niti valley who live by the banks of the trans-Himalayan Dhauli Ganga river. Of mixed Tibetan stock, these tribal people of upper Uttarakhand had been successful traders, carrying on a millennia-old summer trade with Tibet. The 1962 war put an end to that. Later, when the national park came into being and all entry was closed, even the local people who’d led a symbiotic relationship with Nanda Devi and her valleys and grazing grounds, found the way barred, and their rights superceded.

It was in Lata, and nearby Reni, that the famous Chipko movement began in 1974 to prevent the decimation of sacred deodar groves around these two villages. In the late 1990s, these same villagers fought a long-drawn-out campaign for community participation in the management of the national park. Dhan Singh was a part of both these efforts. In the former he was a defiant boy standing up to forest contractors. During the latter, he was the village sarpanch who cannily organised the villages into a formidable body of activists. An offshoot of this movement was the opening and maintenance of certain trails within the park where local men could act as guides.

Narendra is a shy, soft-spoken man in his mid-twenties. However, the last few days in the wilderness seemed to have wrought a subtle change in him. In addition to the deepening stubble on his angular face, there was a flashing brightness in his eyes, a sharpness of sight. He was beaming as he hid behind a rock and took pictures of the bharal. He loved being here, back after many years. He mostly works in Dehradun now. The last time he’d come this way, he was accompanying a scientific expedition to the inner sanctuary. He still hadn’t forgotten the awe he felt in the presence of Nanda Devi, a mountain that was also a goddess.

And with good reason. My companion Parth and I had arrived in Lata five days before, on a sunny day in early September. It was the last day of the annual Nandashtami celebrations. The devi’s origins lie in ancient nature cults. Indeed, in the older temples of Kumaon, her image is that of a tribal woman. Today, to outsiders she is just another reincarnation of Parvati or Durga, but to the Bhotias Nanda is herself, the powerful queen of her mountain realm, the bliss-giving goddess. Sitting in front of Nanda’s medieval temple, studded with brahma-kamals to mark the occasion, I felt as if I was watching something unfamilar, something special. This wasn’t Hinduism as I knew it. Women in Tibetan-style long black robes and white cloth headscarves danced slowly in a circle while chanting a plaintive song of regeneration and permanence. Then Nanda herself entered the body of her priest, who, dressed in her ceremonial regalia, blessed the villagers and two large rams brought as offering. These were then summarily sacrificed. The sun gradually sank to the west, and the puja was over. The children of the village who’d been waiting patiently all this while swarmed up the walls of the temple, clambering up with the agility of sure-footed cragsmen to get at their prize — a brahma-kamal.

The Nanda Devi Sanctuary lies across the Great Himalayan Range in the form of a ring of high mountains. Bang in the middle of the eastern curve of this cirque sit the twin peaks of Nanda Devi, looming over some 380 sq km of ice and snow. Nowhere in its 110km length is this mountain wall less than 18,000ft high except at a single point in this chain, where the Rishi cuts through the barrier and flows west to meet the larger Dhauli. The only practicable route into the inner reaches of the sanctuary is by outflanking the precipitous outer gorge of the Rishi Ganga and crossing the 13,950ft Dharansi pass to Dharansi and then down over the Malathuni Pass to the upper Rishi Ganga gorge.

Four days after witnessing the puja, I was 6,500ft above Lata, beyond the ridge of Jhandi Dhar, trudging along a series of rock gullies and defiles, making for the Dharansi pass. Like all my days here so far, it too was a dark, gloomy one full of mists and sudden rains. They say that the goddess delights in her ‘chhaya-maya’, a veil of magic that she often casts on her land so that unwanted folks do not come prying.

Did she then consider us dangerous interlopers? Since we’d set out from Lata, there had been an earthquake — we slept up on a cliff while Delhi shook — a violent cloudburst and no sign of Nanda. Add to that the fact that Parth had recently been rendered hors de combat by the unforgiving terrain. He couldn’t tackle the near-vertical cliff faces with his troublesome knee and non-existent fitness. He’d come as far as he could, mostly by sheer willpower, but he prudently chose to return to Lata Kharak. Raghubir Singh had returned with him, after ferrying me the one camera Parth could spare. It was generous of Parth to do so. So our depleted party walked up Bhafgheyana Dhar, and through a notch in the ridge entered the notorious cliff traverse of Satkula, the gateway to Dharansi.

The broken jagged precipices of Satkula cunningly hide the valley. The only way through is over an exceedingly steep goat track. From that initial notch, it descends right down to a gully before trudging back laboriously up to the next cliff face to another notch in the skyline before plunging down the next gully. It’s beastly hard in the rain, especially in the middle of a heavy fog; one misstep will send you hurtling some 8,000ft into the Rishi gorge. The pass itself is the last link in this chain of convenient notches in the broken ridge-system. But to me, the true entrance was the impressive stone goat arch of Ranikhola, one that the writer Bill Aitken memorably described as a goat’s Arc de Triomphe. It is said that when the shepherds brought their charges to Dharansi, a Bhotia maiden dedicated to Nanda would stand guard here, counting each goat and sheep as it passed through the gateway.

That evening in Dharansi proved to be the first thawing of Nanda’s suspicion of this motley group of out-of-season trespassers. Along with the shockingly tame bharal came a spectacular sunset. The sky had cleared in the direction of the Dhauli valley and the sun was setting above the distant peaks of Chaukhamba, painting the film of clouds on the western horizon an angry red. Steady streams of thick vapours were flowing down over the strangely shaped pinnacles overhanging the Rishi gorge. Other clouds formed impossibly long banners that draped themselves over the prominent peaks to the south — Bethartoli Himal and Ronti. Up east the sanctuary was still cloaked in heavy clouds. But as I looked up the slope I was mystified to see what looked like a luminous mist playing on the uppermost reaches of the bugyal. Glowing orange and yellow, the mist was the last to disappear, leaving us with a dark night so still and silent I could hear my own heart beat.

I rose early, only for my jaw to drop as soon as I stepped outside the tent. Everything was unbelievably clear. Beyond the Dharansi cutoff the distant Dhauli and Alaknanda valleys were drowning in a low layer of clouds. But above that all was clear. Far to the northwest ran a set of peaks I was very familiar with — the Kedarnath group and the Chaukhamba massif that contain the Gangotri glacier. A little to their right rose the triangular southeast face of Neelkanth, the peak that towers over Badrinath.

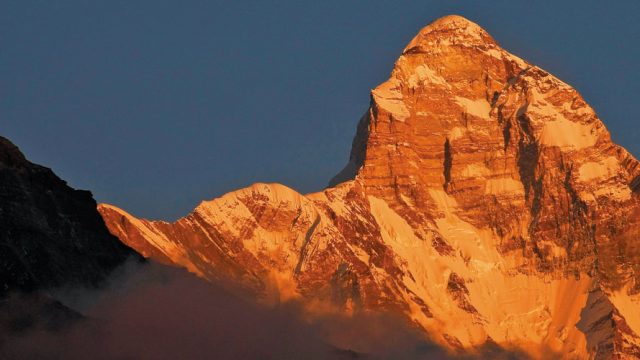

To my right, the delicate ice flutings of Bethartoli Himal were a blushing pink in the diffused light of the rising sun. Even the Devistan peaks that formed the dividing ridge between the inner and outer sanctuary were out. Would Nanda be revealed at last? Her peak couldn’t be seen from camp so Narendra and I ran around to the southern enclosing wall of the valley. We drew up to Malathuni pass, panting, with our boots soaked by the heavy dew. There she was, Nanda Devi, her west face in shadow, but her pinnacle proud and true, sailing through the heavens without any wind. The people of Lata were right. She was herself and no other. Looking at her strange, fearful symmetry it is no wonder that Nanda Devi the mountain and Nanda the goddess are considered one and the same, indivisible.

At the lovely alp of Dibrughati, 2,000ft below us, it was still night. Yet, across the gorge, the green side valley of Dudh Ganga — that descends from the combined snows of Trisul and Bethartoli — looked exactly like a sun-kissed CGI valley. To my left Dunagiri’s peak was lost in a maelstrom. But the majestic shoulders of this giant stood out, the snow glinting in the sunshine. The sun started peeking out from behind Hanuman, and slowly the Dharansi alp started shining a bright emerald green, of a kind I don’t remember seeing before. Lammergeiers flew overhead in slow arcs while tiny swallows leapt down into this amazing scene of wild gorges and snow peaks. A mouse hare emerged to sun himself. I sat there for hours, staring, until swirling mists from the Rishi slowly hid the world again.

The Information

Nanda Devi NP

The national park lies in central Uttarakhand across the main crest of the Great Himalayan Range. The core sanctuary covers an area of 380 sq km. This is a part of the larger national park measuring 630 sq km, which also contains the Rishi Ganga gorge and its surroundings. The village of Lata lies on the westernmost edge of the park. The park forms a part of the larger Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve which covers an area of 223,674ha spread over northern Garhwal and Kumaon. The national park was instituted in 1982 following grave concerns over environmental degradation. It was recognised as a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1988.

Getting There

The roadhead of Lata village is approximately 516km by road from Delhi. You can book a one-way taxi for Rs 8,500 to take you to Joshimath. This takes roughly fifteen hours unless you are held up by landslides and roadblocks — something not uncommon on the NH-58 till Joshimath. Shared taxis run from Rishikesh to Joshimath at Rs 400 per seat. Lata is another 30km away on the new highway that runs till Malari in the Niti valley. You could either book a jeep from Joshimath to Lata for Rs 700 or take the shared option for Rs 30 per seat.

Preparations

Although this is a short trek, it’s a fairly arduous one, so you need to be very fit to tackle it. The track is unsuitable for ponies, so despite taking porters along, you will need to carry at least some of your luggage yourself.

The best season for this trek is from mid-September till late November. It can also be done in the months of May and June, but then you will have to be prepared to flog a route through heavy snow in the higher reaches of the trail, which makes some of the trickier parts of the trail even more hairy. The long post-monsoon stretch of clear days and non-slippery rocks is when you should try and attempt the trek.

Unless you’ve arranged for these via your trekking operator, you will need to carry a good down sleeping bag and a dome-style two-man tent. You will also need a good pair of waterproof hiking boots. There’s a lot of vertical clambering over loose rocks, so a good grip is essential. Since Nanda Devi is a national park with restricted movements, you will need to get a forest permit from the office of the Divisional Forest Officer in Joshimath. Despite the permit you are not allowed to cross the Rishi Ganga. Your trekking operator can get this organised easily. Keep a day or two in hand in case you get held up due to bad weather.

Potable water is scarce from the second day onwards, so you should ensure that you’re carrying enough water for a few days. If your guides know the area well, they will be able to keep you supplied with fresh water.

If you’re tiring, never be the last person on the trail. The forests are full of black bears as well as the occasional leopard.

The Route

Day 1: Lata village (6,998FT)-Kanook (9,400FT)/6 km

A leisurely walk through the forest, it should take you about four hours. You can stay overnight in tents. However, if you want to camp near flowing water then you can stop at Bhelta in the forest.

Day 2: Kanook– Lata Kharak (12,336FT)/6km

This is the first steep stretch so start early. The walk usually takes about four to five hours through constantly changing forests of deodar, chir and blue pines.

Day 3: Lata Kharak -Saini Kharak (12,467FT) and back

This day should be kept aside for acclimatising and wandering about the ridge-tops. You get great views of the Garhwal Himalaya from both these grazing grounds. Musk deer abound in the dwarf rhododendron forests just below Lata Kharak.

Day 4: Lata Kharak-Dharansi (13,780FT) /13km

This is the toughest day. The route is almost entirely over rocks and cliff-faces. Beyond the ridges of Jhandi Dhar and Bhafgheyana Dhar, there is a spectacular cliff traverse over the broken precipices of Satkula. Watch where you’re stepping and be mindful of falling rocks. You should start as early as possible so that you reach Dharansi with enough daylight to spare. Never try to cross this stretch when it’s raining. You will encounter packed snow in May and late November, so you should come equipped with ice axes and the know-how to use them.

Day 5: Dharansi

You should ideally give yourself an entire day at Dharansi and go rambling about the hanging valley. It’s a great place for views. Keep a lookout for the wildlife, especially bharal and ibex. If you’re very lucky, you could even catch a glimpse of the snow leopard. If you’re up early enough and are fit, you could descend to the alp of Dibrughati (11,480FT). However, you should only try this if your permit covers Dibrughati.

Day 6: Dharansi-Kadi Chaun (10,072FT)/13km

Retrace your steps till Jhandi Dhar and then take the trail to Tolma and camp in the thick forests of Kadi Chaun. As an alternative, you could return to Lata Kharak and go down the next day to Lata. If you’re in a tearing hurry, as I was, then it is possible to descend all the way to Lata, a mammoth ten-hour hike. I sprained my knee badly due to sheer exhaustion. Definitely not advisable.

Day 7: Kadi Chaun-Tolma and Suraithota (7,037FT)/8km

Suraithota is the roadhead. You can catch shared jeeps going from Malari to Joshimath.

Trek operator

I used the services of Mountain Shepherds, a loose body of Bhotia guides and porters from the villages of Tolma and Lata. This is an offshoot of the Nanda Devi Campaign for cultural survival and sustainable livelihoods. Narendra Singh Rana was my guide and I couldn’t have asked for anyone better. They charge daily porter and guide fees of Rs 400 per person per parao (day’s walk) while on the move and the same rate per day for rest days. This is exclusive of rations and fuel. Tents can be hired for a one-time payment of Rs 1,000. Homestays at Lata and Tolma cost Rs 400 per person per day. The forest permit comes to approximately Rs 1,500 per person depending on length of stay. Contact Sunil Kainthola 9719316777, bhotiya@gmail.com, mountainshepherds.com