It’s 6am on my last day in Uzbekistan and I’m the only one having breakfast in the garish, chandelier-lit dining hall of Hotel Uzbekistan. Nobody’s watching, so I slip figs and walnuts from the buffet into my backpack for munching on later. The Fergana valley is the last stop on my Uzbekistan tour. As I’m finishing coffee, my guide, Gulnoza, calls.

Gulnoza is a divorced mother of three and she’s originally from Fergana. She teaches English part-time and works as a tour guide to make ends meet. She recently ended her abusive marriage to a man who only married her so he could move into her apartment in Tashkent. Her sister babysits her kids when she’s off on tours. She appears tired and burdened like many multitasking single mothers. She tells me about the busload of 56 Indian men she took to Samarkand yesterday. “They not interested in history,” she says, glancing at me, as if to gauge whether I knew what they were really interested in.

“I’m interested in history,” I assert, in case she assumes lack of interest in history to be a national trait. “Babur, the founder of the Mughal empire in India, he was from Fergana, you know?”

“Of course I know,” Gulnoza perks up. “King Babor! Your ancestor?”

“No, not exactly.”

It’s a glorious late spring morning and you wonder why the streets of India aren’t more like the streets of Tashkent, with such splashes of tender green, such clean, wide footpaths, such gracious trees. Because quiet and uncrowded are words that have long been deleted from the urban Indian psyche, I feel bewildered in the quiet, uncrowdedness of Tashkent. Can I be blamed? The entire population of Uzbekistan would make up two Delhis.

We are on the multi-laned, smooth-as-a-fish-belly highway heading southeast. I’m struck by the total lack of vehicles on the highways and the vastness of the Uzbek landscape. Blood-red fields of poppy swish past, a sky whose blueness is beyond words, and lakes for which emerald is the only apt adjective. Our driver, Agha Shakir, forgets to take his foot off the accelerator. On such underutilised highways, I might do the same. What on earth could have incited Babur to leave a land such as this and settle for the dusty plains of north India?

Gulnoza gives me a quick history lesson. “Babor tried to defeat Shaybani Shah, the Uzbek king of Samarkand. He fight Shaybani Shah but lose. He was put into prison. Khanzada Begum, she was a sister of Babor, very beautiful, very intelligent, she wrote poetry. When Shaybani see her, he fall in love. He asked her to marry him. She refused. When Babor was in prison, she went to Shaybani and says: ‘If you free my brother, I will be your wife.’ So Shaybani marry her and Babor escaped to Afghanistan. From there he goes to India and makes Mughal empire. Babor put to shame, you see, so he had to leave Uzbekistan.”

So I learn that sacrifices made by a sister were instrumental in helping the founding of an empire. I guess valour’s flip side is shame. For some men humiliation, limitations and constrictions become springboards for spiritual advancement; for others, the compulsion to establish empires.

Entry to Fergana is restricted. Fergana valley has been the hotbed of Islamist militant activity and we’re nearing a security check post. Some militant groups have advocated the ouster of president Islam Karimov, the ironfisted Uzbek who has ruled for almost two and a half decades since the country gained its independence from the Soviet Union.

An officer wants to see Gulnoza’s passport and my registration. I hand him the registration slip I received at the hotel. “Registration,” he repeats. Confused, I hand him my passport. “No. No. Registration!” he insists. Gulnoza has forgotten her passport at home. We look helplessly at each other. The officer tells us there can be no entry without proper documents.

“I talk to them,” Gulnoza says, and whispers as she’s getting out of the car: “Maybe I bribe them.”

She follows the officer to a squat building on the side of the highway. I wait in the car for a while and then get out to enjoy the rural landscape. It’s a crystalline morning made for reveries. The breeze is soft, men are fishing in an emerald lake, and a donkey is feasting on ample grass under a turquoise sky. Snow-capped mountains sparkle in the distance. I sit and stare, grateful for the unhurriedness of my day. The thought arises that we might not be able to enter Fergana, but it doesn’t matter. Either way, my gut says it’s going to be okay.

After about an hour, Gulnoza appears, smiling.

“I tell them King Babor was your ancestor. You have come from India to visit the land of your ancestor on your last day in Uzbekistan.”

I can’t believe they bought that!

“We bring back gift for officer,” Gulnoza says.

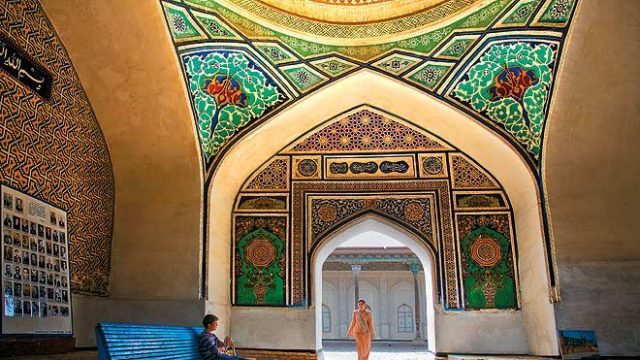

A couple of hours later, we enter the city of Kokand, the pearl of Fergana. First stop is Khudayar Khan’s palace in the centre of the city, built in the 19th century by the last Kokand Khanate king. I stare at wall after wall of intricate blue, green, maroon and ochre tile work, flowery calligraphy, delicately carved wooden doorways. I can relate to some aspects of all these cultural artifacts, the Muslim names of rulers, and the architectural styles of the domes and arches and their scriptural ornamentation. I can read the Persian and Arabic calligraphy on the walls, but I don’t know what the words mean. I feel like an insider and an outsider. I came to Uzbekistan to find some sort of spiritual connection, which I certainly didn’t find in the historical sites, but I did in the people; good-natured, curious and hospitable people who shared food and photographs with me on trains from Samarkand to Bukhara and from Khiva to Tashkent.

Next we go to the Juma mosque where afternoon prayers have just ended. Groups of rosy-cheeked Uzbek men in embroidered caps are standing outside the mosque, chatting amiably. Nobody seems to be in a hurry to get anywhere. Unlike the mosques of the subcontinent, where the prayer call is broadcast on loudspeakers five times a day, this practice is outlawed in Uzbekistan. People show up for prayers at the mosques at designated times without being summoned by loud, unmelodious maulvis. Gulnoza keeps talking, having memorised spiels for all the palaces, mosques, and mausoleums and madrassas. After Juma mosque, it’s the Dahman Shakon complex and Modari Khan’s mausoleum where Nadira, the famous 19th-century Uzbek poet and princess, was buried. She was put to death by the Emir of Bukhara when he defeated the Khanate ruler. In mid-20th century, her remains were moved to another spot in the cemetery.

A guide appears from somewhere and reminds me of guides who insist on becoming your guides at Indian monuments. He talks, Gulnoza translates. A group of school girls want their picture taken with me. “You are from India!” they exclaim and I feel flattered for a moment, but realise Bollywood has something to do with the interest I elicited. They prattle off names of recent movies they’ve watched. We can’t converse about much else in a common language.

At last exhausted, I pay the guide and Gulnoza and I sit down on a stone bench under a tree with the serenity of graves around us. I am surrounded by the paradox of human arrogance, transcendence and ultimate insignificance. I witnessed it in the officer’s sudden refusal, then his change of heart and here in the grand monuments built by ambitious rulers who lie as dust. All of which leaves me awed and humbled and bewildered. The exquisiteness of classical Uzbek architecture is about human ingenuity as much as it is about human frailty. Islamic aesthetics fused with Chinese, Persian and Central Asian influences. Geometric designs, trance-inducing patterns within patterns, and the stunning creative capacity to utilise line, form and colour to convey the unconveyable.

I can’t take in any more history, so I suggest lunch. We eat the Uzbeki bread called non, kebab, and red peppers in a vinegary dressing washed down with lots of weak tea. And the entire bill for the three of us comes to about $4!

Fergana is famed for its fruit. On the way back, we stop at an outdoor market. We have to get gifts for the officer and I want to take home some apricot jam. Apricots are available fresh, dried and canned, but there’s no apricot jam. Disappointed, we return to the car empty-handed to find a woman arguing with our driver.

“What is she saying?”

“She’s selling medicines.” Gulnoza says no more so I ask Agha Shakir.

“Viagra,” he replies.

Each ‘Twelfth Night’ has the picture of a naked man, a naked woman on top, and another in his arms. Individually wrapped. Made in China. But why is an erection-sustaining pill marketed as Twelfth Night?

“I’ll buy two,” I say.

Gulnoza looks puzzled. “You want? It’s only for men.”

“Yes, but it’ll make a nice souvenir!”

A deal is struck. The lady brings out her entire stock hidden inside the folds of her burqa. That’s 45 Twelfth Nights for 40,000 soms (about $16). I pay 2,200 soms for my two.

“What’s Shakir going to do with them?”

Gulnoza chuckles: “Sell at higher price to tourists in Tashkent.”

Back at the check post, Gulnoza and I meet the officer who had allowed us to visit my supposed ancestor who was born in Fergana but buried in Afghanistan. Gulnoza showers the office with rehmats (thank yous) and we unload our offerings on his desk: fresh Uzbek bread, fruit and chocolates.

As we drive back to Tashkent, I wonder if the world has changed much from Babur’s time. Our reality in the 21st century is still about war and violence, empire-building, corruption, and poverty; men’s narrow definition of what it means to be a man is still compelling them to purchase medically-enhanced masculinity. But there’s a silver lining: it’s much better to be born a woman today. Even the most privileged Muslim women in Babur’s time had few options for exercising personal agency. Even the ordinary Muslim woman today is better off by comparison: she can end an abusive marriage, work as a tour guide, sell Viagra if she has to for a living, or like me, set out on a journey to Uzbekistan.

The information

Getting there: Uzbekistan Airway and Air Astana fly the Delhi-Tashkent round trip from about Rs 38,000. Choose a tour package that includes the Fergana valley to get there. Like several other operators, Zamin Travel (00998366, www.zt-ouzbekistan.com) offers all-inclusive packages to cover the main destinations of tourist interest in Uzbekistan. A long day trip is enough to visit the key historic sites in Fergana. Tashkent to Kokand (227km) takes about 3-4 hours by car, depending on how quickly you get through the check post.

Visa: It’s best to book a tour with a tour agency; they apply for a tourist visa on your behalf to the Republic of Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (www.uzbekembassy.in/embassy/consular-section). The LOI (letter of invitation) is issued by the ministry and is required for visas. Visa processing takes about ten days. Fee for a single-entry tourist visa valid for seven days is about $40.

Currency: Rs 100 = approx 4,000 UZS (Uzbekistani Som). US$100 will get you about UZS 244,000. Be prepared to carry wads of Uzbek money. The best exchange rates are to be found at unofficial money-changing outlets; you’ll find that even juice and snack kiosks offer these services.

Where to stay: Hotel accommodation is usually included in the tour package and you can ask for it to be customised to your preference. I stayed at Hotel Uzbekistan (from $80 inclusive breakfast; www.hoteluzbekistan.uz/en) in Tashkent. The hotel’s Sovietera architecture is aesthetically unappealing; and the hotel staff was not unfriendly, just inefficient. Don’t expect too much from the hotels in Tashkent. The Radisson Blu Hotel Tashkent (from $150; www.radissonblu.com/hotel-tashkent) is among the better hotels in the Uzbek capital but it doesn’t match the Radisson standards found elsewhere. You may like the welllocated Lotte City Hotel Tashkent Palace (from $140; www.lottehotel.com/city/tashkentpalace/en) better for its courteous service, but beware of rooms above the loud karaoke bar. Hotel reception takes care of the mandated police registration as soon as you arrive at each destination within Uzbekistan.

What to see & do: In the city of Kokand in the Fergana valley, visit Khudayar Khan’s 19th-century palace in the heart of the city, the Juma mosque, the Dahman Shakon complex, and Modari Khan’s mausoleum where Nadira, the famous 19th-century Uzbek poet and princess, was buried. You must visit the outdoor fruit and vegetable markets for a visual feast, and have chai at a traditional Uzbek chaikhona, seated on carpeted divans against luxurious cushions. I would recommend travelling by train within Uzbekistan. Trains are clean and inexpensive, but don’t always run ontime. Train travel is one of the best ways to meet locals and experience their hospitality and friendliness.

Where to eat: I mostly ate at small cafés. Fresh Uzbek bread and a wide variety of fruit make for a very satisfying meal. Uzbek pulao is great; it’s delicately flavoured with spices, nuts and raisins but available only at lunchtime. Barbecued meat is popular, for example, chicken and lamb kebabs. Uzbek food is generally very mildly spiced, so vegetarians and lovers of spicy food may have a hard time here.

Top tip: There’s lovely pottery and embroidery to be found in Uzbekistan, but you should be prepared to bargain down prices.