Historically, Lucknow was a cultural melting pot in the erstwhile Kingdom of Awadh. Food, literature, dance, and poetry—all the finer aspects of life flourished under the patronage of its colourful nawabs, chief among whom was the last Nawab of Lucknow, Wajid Ali Shah. He was considered a cultural luminary of his times and continues to be remembered for his fascinating life, immortalised in Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khilari.

The Wajid Ali Shah festival, organised by the Rumi Foundation and supported by the Uttar Pradesh Tourism Department, celebrates the legacy of the eponymous Nawab. It also highlights the syncretic traditions and culture of this region—for Awadh is renowned not only for its genteel charm, grace and exquisite courtliness, but also its secular traditions and inclusive worldview. A harmonious amalgamation of diverse cultures thrives within its folds, known as the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb.

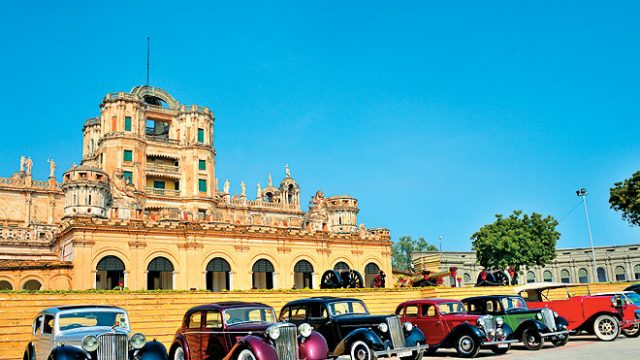

The second edition of the festival (February 23–24) showcased this rich heritage through a deliciously inventive panoply of events. The attractions were not paraded in a routine display for visitors. Instead, performances were handpicked from a vibrant palette and juxtaposed onto the architectural heritage of the city, infusing life into these cultural landmarks. A winning combination was the poetry recital by Shanney Naqvi within the massive chambers of the Bara Imambara. It transported the spectators to a magical era of resplendent colours, with a touch of sepia at the edges. Another memorable event was the tour of the city in vintage cars. It was a sight to behold: the priceless beauties chugging down the roads, with city traffic whizzing by.

It is only fitting that the festival opened at one of the enduring vestiges of Awadh’s courtly culture—the Jehangirabad Palace—with a spirited kathak dance performed with trademark panache.

The tour de force, however, was Indrasabha or the ‘The Heavenly Court of Indira’, an opera-drama directed by renowned director Muzaffar Ali. It is a gripping tale of celestial beings—apsaras and gods—struggling with human emotions of love, loss and longing. The story written by the 19th-century poet Agha Hasan Amanat was first presented in the palace courtyard of Wajid Ali Shah, and was a runaway success at the time. Its current version was played out in a surreal theatre—the ruins of the British Residency, the former township of the British crown in Lucknow that was devastated in the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

The festival concluded with a tribute to one of the most passionate and radical poet-philosophers of the 13th century, Jalaluddin Rumi. The rumiana session was held in the hallowed chapel of La Martiniere College. A swashbuckling Frenchman, Major General Claude Martin, built this building, also known as Constantia. A good friend of the Nawab, he was an avant-garde who made Lucknow his adopted home and is credited with a host of splendid structures across the city.

It is often said that Lucknow is known for its kebab, shabab and nawab. In years to come, it will be more precisely known for its last nawab, as the Wajid Ali Shah festival continues to captivate its audience— locals and visitors alike.