Four days before I came to Jerusalem, the Pope was here, and reminders of his visit still fluttered in the form of little flags strung across the alleys of the Old City’s Christian quarter. The day of my arrival, a leading rabbi had died, and traffic into the city was complicated by the funeral procession. It was also the anniversary of the ‘liberation’ of East Jerusalem — from Jordan, during the Six-Day War in 1967 — and posses of young Jewish men, in yarmulkes and white shirts and blue trousers, rumbled through the Old City’s streets, singing menacing anthems of celebration.

All this seemed entirely appropriate. It felt like Jerusalem must always be this way: embroiled in its faiths, conflicted about its identity, perched on the cusp of a fight. Some countries are a product of geography, others of migration or colonialism. More than any other nation, Israel is a product of religion and war, the two forces packed so tightly together that it is difficult to determine where one ends and the other begins. Two months after my visit, when Israel began to pummel Gaza, I wasn’t surprised; I still remembered that brittle, aggressive atmosphere, just waiting for a strike of tinder.

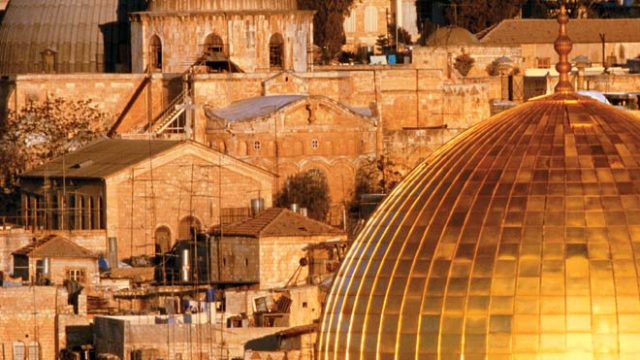

In the view of Jerusalem from Mount Scopus, the Old City lies cupped among the hills, shining in the sun, its buildings all clad in blinding white dolomite. At its heart is the most storied parcel of land in the world, which once held the Temple of Solomon and is now home to the Al Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, its half-orb covered in gold, marking the spot where Muhammad rose into heaven. Just beyond is the Western Wall — the Wailing Wall — and then the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built on the site of Christ’s crucifixion. Innumerable armies have desired these treasures and fought to possess them. Richard the Lionheart, beholding this view once during the Third Crusade, could not bear to look upon a city he could not seize. He cried out in despair, raising his shield to hide Jerusalem’s unattainable glory.

Such legend is thick on the ground in Jerusalem, visceral and entrancing. It fires the imagination in a way that pure history never can, and this in turn stokes the fervour of religion. Jerusalem is always what your imagination can make of it.

In the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, people keened and prayed over a slab of polished wood, upon which Christ’s crucified body was supposedly washed before burial. The word ‘supposedly’ works hard here; there is a column of rock upon which the cross was supposedly erected, as well as a star supposedly marking the precise spot of the crucifixion. Two central enclosures were swarmed by pilgrims, both supposedly the tomb that held Jesus for three days; the bigger belonged to the Greek Orthodox Church and the smaller to the Coptic Church.

“But come here,” my guide, a 71-year-old man named Eli Gertler, said. He led me to another niche, a low cave with walls darkened by the soot from a million candles. “This was where Jesus was really buried.”

And yet there were no pilgrims here at all, in this cramped grotto unsanctified and unrecognised by the world’s leading churches; they were all in the main chamber, experiencing paroxysms of devotion in the two ‘official’ tombs. On the other hand, what did Eli even mean when he insisted that Christ had been ‘really’ buried here? There was no way to know. Jerusalem frequently robs words of their meanings.

Even agnostics can fall into a mild version of the religious psychosis called the Jerusalem Syndrome. I got gooseflesh more than once, from how charged the air around me was with spiritual faith: at the Western Wall, where Jews lamented against the high, impassive dolomite; on the Via Dolorosa, along which Christ is mistakenly assumed to have dragged his cross; looking up at Mount Zion, where David, slayer of Goliath, built his palace; hearing the muezzin’s call, in the city towards which Muhammad originally urged his followers to face when they prayed. All religion may be a mirage, but few places conjure up these mirages better than Jerusalem, this overheated outpost in the desert.

Fortunately, the Old City supplies its own cure for such stupefactions. A ramble through its slender streets brought me back from the sublime into contact with the stuff of everyday life. There were carts vending freshly juiced oranges, tasting like sunlight in a glass. There were stores selling Armenian ceramics, Jewish memorabilia, prints and paintings, scarves and prayer mats, and souvenirs of Jerusalem. I browsed through spices in the Arab quarter, the shops so close on either side of me that they blocked out the sun. We found a shoebox-sized café and sat down for glasses of Turkish coffee, dense as treacle. The proprietor, a Greek man of aristocratic bearing, sat at the entrance in immaculate attire: a tie, trousers and a vest, as if he only needed to throw on a blazer before addressing the stockholders of his cement corporation.

In the Christian quarter, Simon Katan fell into conversation with us. He was sitting outside his shop selling scarves and busts of Jesus, his hair white and his belly round and proud. Once, Katan said, he was sitting indoors at his counter, when a couple of nuns passed by on the street. He saw them through the glass façade of the shop, and one of them looked familiar. “‘Sister Mary! Sister Mary of the Visitation!’ I shouted, or something like that, and I ran outside,” Katan said. “She also came running back, and it was her!” Just a few days previously, he had received a Christmas card from Europe, manufactured for charity by Sister Mary’s order and featuring her face on the cover. “It was such a coincidence,” Katan mused. “But then again, the whole world passes through Jerusalem.”

Driving into Jerusalem from the south, it is not difficult to understand why so many prophets and religions found purchase here. The Negev Desert is parched and unremitting, so brutal that the soul yearns for solace and is forced to ponder the meaning of life. The very air tastes of salt, and the heat bounces off the baked wadis. The rock here was eroded long ago by water and more recently by wind, and the projections from cliff faces look like noble noses. Guides conduct trips into the desert, their jeeps jouncing around in the dust; campgrounds offer tent lodging for the more hardy travellers.

At its north, the Negev borders that other geographical body massively inhospitable to life: the Dead Sea. But just as man has tamed the Negev — luxury hotels; hothouse grape cultivation; even swimming pools — so has the Dead Sea been sprinkled with life, in the form of tourists wading into its oleaginous waters. A grimace is inevitable as you lower yourself, rump-first, into a floating position, because the salt mercilessly attacks the tiniest cuts and scrapes anywhere on your body. (If your back happens to be freshly sunburned, as mine was, that is a special category of hell). In resorts ringing the Dead Sea, spas offer Dead Sea mud treatments and cosmetics packed with Dead Sea minerals, but these feel like faint shadows of the real thing. The true lure is what the Sea itself provides: those hedonic minutes of floating without effort, limbs weightless and utterly relaxed, in a brackish version of zero gravity.

A short drive from the Dead Sea is Masada, the ruin of a once impregnable fortress built in the middle of the desert, on an ochre cliff, by the paranoid Herod the Great around 35 BCE. At the foot of the cliff, Nubian ibexes grazed on the patchy vegetation; there is water underground here somewhere, which was why Herod had chosen it as the location for his stronghold. Most of Masada’s walls are long gone, but its layout is intact, with low stones marking the imprint of the palace upon the rock. The occasional preserved or reconstructed room — such as the tepidarium and caldarium of the bathhouse, with some of the original mosaic still in place — felt like a miracle. In another chamber, behind a glass wall that retained his air conditioning, a grey-bearded man wrote out the Torah by hand, watched all the while by tourists; it was as much performance as scholarship.

We saw more ruins by the sea at Caesarea, where Herod had built a hippodrome and an amphitheatre, and at Acre, where the old city includes a citadel of an order of crusading knights, complete with pinched underground passages for hasty escapes. After such sights, Tel Aviv will feel new and brash, with its shiny corporate towers, modern condominiums, and hipster boutiques. Tel Aviv, they told us, is Party Central in Israel, with clubs that crank out funk and techno until dawn, and cocktail bars where you could stand around all night without finding a seat. Somehow, this didn’t excite me. I walked desultorily along boulevards such as Sheinkin, with its Bauhaus-inflected buildings, jewellery design studios and footwear emporia; apart from the occasional poster of Moshe Dayan that popped up in a window display, I could have been in any European town. What I wanted was more of the Crusades and the Old Testament, and the romance of old stone glowing in the sun.

Fortunately there is Jaffa, the port town attached at the navel to Tel Aviv, conquered once by David and Solomon and Richard the Lionheart. Jaffa is an agonised town, its Arab residents claiming that the government is attempting to turn it entirely Jewish, using the sort of strong-arm tactics with which the state has come to be associated. But charm oozes out of Jaffa’s tourist quarter. Its cobbled alleys run past quiet cafés and roaring restaurants, through flea markets, and past shops selling antiques and art and pomegranate wine. Some streets lead to the old port, now largely defunct, the Jaffa orange warehouses turned into bars and jazz clubs. On the boardwalk, as the sun sets, restaurants set out tables that fill up with wine and mezze and giant saucers of hummus, and the dusk is punctuated with the soft flashes of iPhones taking selfies. Only a few feet away, it is easy to forget, is the waterfront where army after army landed, over three millennia, all headed with single-minded intensity for Jerusalem.

The information

Getting there

El Al, Israel’s national airline, flies direct three times a week from Mumbai to Tel Aviv Yafo (Rs 45,000-50,000 return approximately). Turkish Airlines flies Mumbai-Istanbul and Delhi- Istanbul daily; there are 49 flights a week from Istanbul to Tel Aviv (Rs 40,000 return approximately). Royal Jordanian flies Mumbai-Amman four times a week and Amman-Tel Aviv several times a day (Rs 41,000 return approximately).

Visa

Bank statements for three months, travel insurance valid in Israel, and proof of accommodation are needed. Full details are at www.israelvisa-india.com. Visas cost around Rs 1,300 and take a minimum of five-seven days for processing.

Currency

One Israeli Shekel = Rs 17.3

Where to stay

The Leonardo (www.leonardo-hotels.com) and Dan (www.danhotels.com) chains of hotels provide four- and five-star comforts across the country ($150-260 per night, inclusive of breakfast). The Jerusalem Panorama Hotel ($65 per night; www.jerusalempanoramahotel.com) is a good mid-range option, while the Jaffa Gate Hostel (private rooms from $27 per night; www.jaffa-gate.hostel.com), close to the old city, is another good option.

Getting around

Buses and trains ply between the major cities, although a hired car is advisable for off-road exploring. Within cities, taxis and buses are common; in Jerusalem, a light rail also operates, although the old city is best explored on foot.

What to see & do

Israel’s primary draw is its historical and religious sights: Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall, its churches and mosques, its ancient citadels. Many of these are free to enter and open almost every day. The Yad Vashem (www.yadvashem.org) and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (www.english.imjnet.org.il) provide vital context to the history. Wander through the old cities to discover curio shops, art galleries and quiet cafés.

Where to eat & drink

Ubiquitous falafel stalls provide quick, delicious lunches on the go. In old Jaffa, Dr. Shakshuka (www.shakshuka.rest.co.il) is a popular street restaurant with communal tables serving North African food, including the signature eggs-and-tomatoes shakshuka ($8-$11). In Jerusalem, fine dining can be found in The Eucalyptus (www.the-eucalyptus.com), owned by the renowned chef Moshe Basson, situated near the old city’s Jaffa Gate. Basson recreates indigenous Israeli food, often from near-forgotten recipes; tasting menus run from $58 to $101, exclusive of wine.

Top tip

Israel is hotter than you’d expect, so keep strong sunblock, water and a hat handy at all times. It’s a good idea to hire tour guides when you can afford them as there’s usually a lot more history to a site than is visible on the surface even to sophisticated tourists.