I’d always longed to visit Nagaland. Countless friends from the scenic state, a love for their marvellous, inventive cuisine, and stories of their headhunting forefathers and the particular customs of its various tribes — Ao, Angami, Sema, Konyak, Lotha — all drew me there. But in Dimapur and even Kohima, of Hornbill Festival fame, houses are crowding on each other, urban establishments are setting up shop; Tuensang, in the east, is hard to get to and, frankly, not as much is left of the traditional ways. So when a dear friend set up a resort in the wilds of Nagaland’s Mon district, I decided it was time to go. And what better time than the Aoleong Festival, the area’s annual spring festival. In Mon, that wild, misty, beauteous place, you will find the last vestiges of the village world which once was Nagaland.

Half a day’s drive from Dimapur and a couple of hours’ drive away from Burma, mountainous Mon is the stronghold of the proud Konyak tribe, one of the largest tribes in Nagaland, known for its valour, former headhunting ways and striking face tattoos. Mon consists of a cluster of villages, all an hour or less away from each other. The first week of April every year sees the colourful, rambunctious Aoleong Festival, harbinger of spring and event of the year.

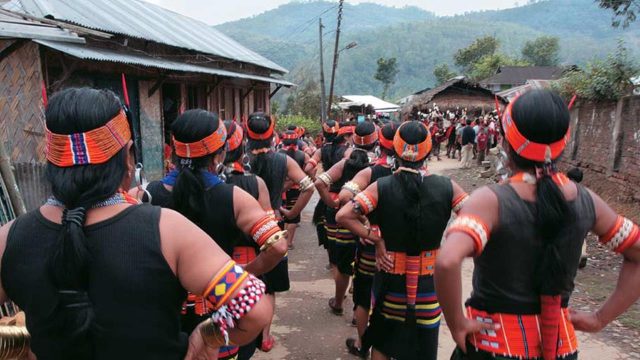

As we drive up the slopes to Mon town, we see them immediately, the stars of the show: the village warriors dressed in all their finery, elderly men with tattoos on their wizened faces, beaded chokers around their necks and little bronze heads that symbolise how many enemy skulls the warrior has claimed; their chests thrust out as they march up the street, spears in hand. What a spectacle they make, and how easy it is to imagine they are on their way to battle. A little girl begins to cry as she watches them strut towards us, and we laugh.

At the Jah-poh-long Mountain View Resort, Shepha and Phejin Wangnao, the charming young couple who have owned and managed it for two years now, check us into our cottages. They’ve both lived outside of Nagaland and have returned to be close to their families and homeland. I’ve always known well-travelled Phejin to be very proud of being a Konyak, and she seems absolutely at home both here and in Dimapur, where the Wangnaos also reside with their daughter Lemei.

There are tents as well, with roomy semi-circular bathrooms and, most of all, there is a gorgeous view of Mon town and the surrounding mountains and valleys. Lunch is in the traditional Naga hut, which is to form a hub of sorts in the days to come, and a little path leads to the kitchen, where Phejin expertly prepares a flavourful Naga chicken dish.

Trekking, angling and birding are all popular activities for the outdoorsy types who pass through here, Shepha tells us. The Wangnaos own and manage Interior Adventures, which coordinates much of this activity. Hailing from Mon village himself, Shepha guides visitors through the area.

We drive to the village, 10 minutes by Tata Sumo (that all-Northeast vehicle), and walk around the settlement of large bamboo huts in the afternoon mist. The houses are unusually large, and we admire their construction and thatch roofs, as we do their huge kitchens, when we are invited inside — the locals are by and large an outgoing, friendly lot. Hanging spectacularly above the hearth is a huge, everlasting bamboo rack, called a phot, on which every family places everything from drying meat to sprigs of leaves and garlic to shoes.

Children are underfoot everywhere — family planning, we wonder? Our photographer Zubeni, a Lotha herself, reminds me that the last census counted a population of only 10 lakh. A mound marked by tallish slabs of stone, we are told, is the site where headhunting trophies (in other words, human skulls) were interred when the village converted to Christianity. Shepha tells us that one village still flaunts a captured skull, to the annoyance of a rival village for whom the skull is an ancestral relic! It was a way of life here, this warring of villages, just as a certain survival-of-the-fittest ethic continues now; meat is scarce in the area, and birds, forest rats, every sort of game, are constantly being hunted. Skulls of every species — mithun to deer to bird — are displayed on the fronts of the huts and inside Mon homes. A little boy brings down two birds every day for Phejin’s cousin, for some pocket money. I can’t help wanting to watch my own head a little, some very buried, ancient instinct for survival stirring to the surface. For the record, though, the dogs of rural Nagaland are not on the menu and, in fact, are often popular household pets.

As we walk past one of the houses, a handsome young man calls us in. “Bhaini,” he calls out to Zubeni, who he proceeds to chat up in Nagamese as we sit with him around his glowing hearth, in his hands a ubiquitous opium pipe. Once the biggest threat to the British in this region — the Konyaks had crafted their own handmade guns, and actively sought to combat the colonisers — the warriors were quelled with opium brought in from Burma. The drug fuels the men here, an expensive habit that lays many to waste. Most smoke the region’s mainstay at least two or three times a day.

Like many around here, our opium-smoking friend’s lips are stained red, unsettlingly, from an excessive fondness for tamul (paan). We watch him with someone who appears to be his assistant or first man in the opiatic world, as they concoct opium from scraps off a sap-filled cloth, and light up. He is immediately animated, and we sit with him for half an hour before we realise that he is the chief angh, or king, of Mon village! Apparently, anghs can be identified by the special turquoise blue-beaded leg bands they wear, and particular Naga hats bearing feathers. Also, we are lucky to have found him, as it is important to visit the angh first and pay your respects, when visiting a village.

In his late 30s now, the angh was only eight when his father died, killed by the underground. The eight-year-old angh was married to a much older woman, as he needed a queen (anghyu) to watch over him, and we learn from others that she moved on and had children with other men. He is free to take on new wives and concubines—his father had 18 wives — but seems wedded to the pipe.

Around the fire at dinner, we meet a jolly French threesome who are touring the Northeast with a guide and an earring-obsessed Australian who is combing the surrounding villages for Konyak ornaments. As always, it seems the foreigners have got here first. But Anuj, who runs a biking adventure company named Chain Reaction, and who we meet the next day accompanying an American mother-daughter biking around Nagaland, tells us that young Indian corporates are hitting this part of the country more and more. With some surprisingly tasty local rice beer, we wash down the pork, greens and chicken aan-soi (chicken stew thickened with ground rice). Everything is smoky and incredibly fresh, and the night sky is that special, mountaintop thing — very black and full of stars.

The next day sees more rumblings of the Aoleong Festival — literally, with the beating of the long log drum. We weave through the mountainside, ravaged by deforestation and jhum cultivation yet pleasantly green with bamboo and filled with birdsong. Today we journey to Lungwa village on the Burmese border, whose angh’s house is famously bisected by the border itself; the front of the house is in India, the kitchen in Burma! Here too we chat with the village angh, equally flamboyant as our Mon chief angh; he sports a cowboy hat with a feather on it. In his living room we spot an odd metal chair; a seat from one of the World War II planes that reportedly crashed in this area and parts of Arunachal, discovered and subsequently gifted to him. This village is particularly large, and also slightly more exposed to tourists; there is a prominent display of opium pipes made of bone, jewellery, masks and swords, all on sale. We visit the murongs — large, high-ceilinged dormitories for young boys who leave their families for a few years to live here, learning the ways of life together and performing assigned tasks for the village when required.

Festival day, April 4, is misty and cold. As the log drums continue to reverberate, we set off to the Aoleong Festival proper, in Mon town. (In every village in this district, similarly, everyone prepares for their own celebration.) Everyone has taken out their traditional finery, even the most urban of the Mon townsfolk sports a Konyak necklace. They wear their shawls, necklaces, traditional woven hats, the men especially conspicuous in their sashes, which are tied across their chests from shoulder to waist. Several hundred locals and some visitors congregate in the festival grounds, and after the pastor blesses the festival — the region contains animists but, we are constantly reminded, is still predominantly Christian — men and women from various tribes get into position. The dancing, chanting and singing commences. The men sport hornbill feathers, woven red sashes, knives with furry tails, spears and bells which are attached to their backs. The women dance more sedately, sporting armbands, belts, waistbands around their shawl-skirts, headbands, intricate earrings and feathers. With their ululating cries and the men’s own deeper singing, a powerful unison emerges. Theatrically, warriors shoot into the air and we gasp — the air is thick with smoke and gunpowder. There is soon a mist of a different kind, a mist of smoke from which warriors can be glimpsed only in intervals, their heads lifted in war cry, guns and spears held aloft in song; the warriors are alive again, it would seem.

Afterwards, there is a feast of luscious pork and rice, the richness meant to be cut by the accompanying passion fruit leaves that we eat raw. Festival day ends by the gooseberry tree just below the resort kitchen hut, which looks out onto the mountains. We drink and listen to the log drum beat on, and are sated.

On the last day, we chat with some young locals from Mon, some of whom plan to continue in the government job track that is almost the edict here, though one wants to learn carpentry. Traditional skills are prized here, but there is also a young person’s longing for progress. Apang Pangyeih, a young student, tells us that Mon and Tuensang were the last to get education and electricity, and seems intent on advancement. The word ‘backward’ has often — carelessly — been applied to the Konyaks, but the truth is that they were in many ways the most advanced and therefore most suppressed by the British. Apang jokes that there are advantages to the word backward that they have to hang on to now.

For here in Mon, kings are still kings, and also opium addicts; warriors are ordinary men, yet, they once were warriors.