If you had come to buy these same gloves a week ago, they would have cost you Rs 90,” announces the woman, holding out a pair of black gloves with a wavy pattern in grey. Perhaps I appear puzzled, because she looks at me with the air of one explaining something to a very stupid child. “Because it was snowing, madam. You couldn’t take your hands out of your pockets even to pick up a cup of tea, without these. But now the sun is out, so…,” she trails off half-heartedly.

With minimal bargaining, we acquire two cheery woollen caps and three pairs of gloves: two black-and-grey ‘Chinese’ ones, one bright blue and hand-knitted. Once breathing into our cupped hands is no longer necessary, we return to our slow amble down the cobblestoned market street that does so much to maintain Kasauli’s reputation as North India’s best-known hill-station-in-a-time-warp.

Family friends and websites alike have told me that Kasauli has “a British colonial feel”, so I’m expecting the cobbled road, gabled roofs and potted geraniums, and even the sight of bread and butter pudding on the Hotel Alasia menu doesn’t surprise me. But it’s the angrez-style weather talk that catches me unawares. “Kaise ho, aunty?” calls a young woman to a sari-clad lady. “Kya thandi hawa chal rahi hai na?” A hotel waiter describes in unsolicited, sorrowful detail at exactly what hour of evening the wind will start to blow, and when a slippery frost will form on the road. Later that afternoon, when Father Ashanand, the gentle young priest who’s just been posted to Kasauli’s old Anglican church, excitedly shows us a musically-annotated video recording of last weekend’s snowstorm on his cellphone, I’m convinced. In Kasauli, the weather is the only news.

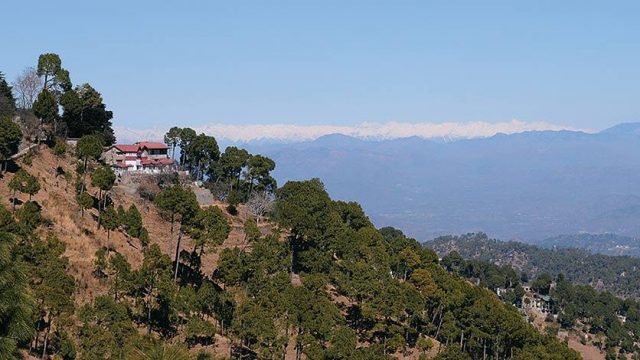

To give Kasauliwallahs some credit, though, winter here does have many shades. It can be wet and windy, grey and gloomy, or as crisp and golden as a crunchy slice of toast. We have good luck — it’s a bleak, grey morning when we arrive, but two almost-toasty days follow. The wind stays sharp as a whiplash, but the sun warms your back as soon as you’re out of the shadows. “Arrey, madam, I can’t tell you how lucky you are,” gushes Aruna, who helps run the reception (and much else) at Ros Common, the Himachal Tourism hotel where we’re staying. “It was raining, then it was snowing. Grey, then white, then grey again — no blue sky. We’ve been aching to see this for two months!” ‘This’ is pronounced while waving expansively in the direction of a semi-circle of snow-clad peaks that seems almost to surround us as we sit in the semi-paved garden of the restored colonial bungalow. I’ve never been much of an enthusiast for mountain views, but this is simply stunning.

Aruna points out the Dhauladhar range and the famous peak called Choor Chandni, all the while providing tidbits about Ros Common’s previous lives. “This used to be a girls’ school, and then a CID office. The hotel started in 1983. I first came here from Shimla with my uncle, in 1987 — it was my first posting. There was none of this cement and paving then, it was a garden: a mass of creepers, and roses and ghadi phool (they look just like the dial of a watch) growing all over the roof. I just took one look at it, and at this view, and fell in love. I’ve been here ever since,” she laughs. The old mali responsible for that glorious garden retired a few years ago, and the riot of life and colour has since receded into a more subdued, matronly existence: black wrought-iron chairs and tables, with only the odd yellow cosmos peeking through. “Lots of things have changed here, even though we tried to preserve everything,” muses a pensive Aruna. “This was built as a private house with interconnected rooms, but we walled up the doors — guests complained about the sound travelling. We replaced the old wood pelmets with curtain rods, but they keep falling off — today’s nails don’t stick in these walls!”

Kasauli has many buildings dating back to the 19th century, though they’ve been through several incarnations since. The imposing grey stone structure of the Protestant Christ Church was erected in the 1840s, and although the fittings were redone over the next 50 years, a lot of the woodwork — the pews, the gallery and the altar — is very old. (There’s also the stone engraving of the Ten Commandments, whose sonorous magic can only be absorbed by reading them aloud when you’re there.) The Lady Linlithgow Sanatorium for tuberculosis patients is now the Research and Training Wing of the Central Research Institute. The Kasauli Club was founded as the Kasauli Reading and Assembly Rooms in 1880, while the twin hotels now known as Maurice and Maidens began life in the 19th century as the Kasauli Hotel and Hotel Grand. The faintly seedy Kalyan Hotel used to be Kali Charan and Sons, a fancy store which stocked French wines, Scotch whiskies, Swiss dry fruits and British cakes and cookies. All that remains of the original owners is the statue of a black cocker spaniel outside, presumably the likeness of a loved pet.

The old may not have stayed unaltered, but not much that’s new is allowed in. The town is administered by a half-military Cantonment Board, which is fairly strict about what it permits. “Construction is not banned entirely, but new properties are not allowed. If you have existing property that you want to build upon, you have to submit a plan of the proposed changes, and a maximum of 10-15 percent increase is allowed,” explains old Mr Gupta, who’s been running Gupta Brothers, Kasauli’s most well-stocked all-purpose store since 1978, and was once elected Vice President of the Cantonment Board. “You see, there are more than 60 bungalows owned by really big guns. And they don’t want anyone new to come in.” Mr Gupta is still smiling sadly when a burly gentleman in the store jumps into the fray. “Hah! All these folk supported the British and got a knighthood,” he smirks, “They don’t want anyone else to get a piece of the pie. The idle rich, y’know, they don’t want the hoi polloi around.”

It’s certainly incredible how many recognisable names from Delhi and Punjab own summer homes in Kasauli. There are the khandani rayees — like Khushwant Singh, whose house is inscribed with the name of his grandfather, Teja Singh Malik; the army-wallahs — a host of generals and brigadiers too numerous to name; the artist-intellectuals — like painter Vivan Sundaram (who recently lent his house to actor Pankaj Kapur when Kapur had trouble finding a place to stay); not to mention doctors and lawyers. More recent arrivals — politicians and cricketers — have to settle for what they can get: a mansion, but outside the town. Surjeet Singh Barnala’s massive estate is on the way down to Parwanoo, while Yuvraj Singh is building his home in Jagjit Nagar, 8km away.

The other source of visitors to Kasauli are the nearby boarding schools — earlier Lawrence School, Sanawar, but now several others. “People come to get their kids admitted, then later to visit them,” says Jai Kishan Thakur of Daily Needs. Thakur and his son Akhilesh are the third and fourth generation to run this popular shop, still remembered for its ham sandwiches and hamburgers by nostalgic old Sanawarians. “Earlier the kids used to come down every Sunday. But recently there have been problems — too much money, drinking, misbehaving with elders. Now students are allowed just one or two trips monthly, and then too accompanied by their teachers,” rues Thakur.

New Sanawarians may have been partially barred from the town, but plenty of the old ones can be found looking down from the walls of Sharma’s Photography Studio. A curly-haired, impish Pooja Bedi (next to her mother Protima) shares space with an impossibly young Maneka Gandhi and an equally unlined Sanjay Dutt. There are also gorgeous portraits of Farooq Sheikh and Deepa Sahi, though it’s only when I see Shah Rukh Khan circa 1990 that I realise why they’re together here. “Yes, Maya Memsaab was shot here,” smiles Mr Sharma. “That house at the corner, opposite the church, was Maya’s house. And Paresh Rawal was the dukandar of the shop next door.”

I summon up my memory of Ketan Mehta’s film, and it’s true, it’s all echoing streets and swirling mists. The mists are missing, but this is certainly the same place, in the same season. We walk all the way up the Upper Mall without meeting anyone except the crotchety old Sikh gentleman who guards the entrance to the Kasauli Club. There’s no sign of students (rowdy or otherwise), or parents, or even the odd brigadier walking his dog. Best of all, there seem to be barely any other tourists — except on the obligatory but pointless trek up to Monkey Point, where a whole busload of college girls were being shepherded along. We see no tourists in two days. But we decide to spend the third morning in even more splendid isolation — walking along Gilbert Trail, a pine-fringed hill path that veers off the tarred road just above the Army Holiday Home. I tread carefully, imagining some memsahib a century ago walking the same path. We walk for two blissful hours without meeting a soul, listening to the wind whistle in the pines. Maybe, I say to myself, Mr Thakur at Daily Needs has a point — “Yeh badal jayega toh phir Kasauli nahi rahega!”

The information

Getting there

By train: Your best options are the Kalka Shatabdi, or the Kalka Mail. From Kalka, the fastest way to get to Kasauli is by road — one hour on a bus, or an overpriced taxi (Rs 700-800). A more picturesque option is to take the Kalka-Shimla ‘toy train’ till Dharampur, from where you can hop on a local bus for the remaining 12 km to Kasauli (Rs 8).

By road: Kasauli is a comfortable 6hr drive from Delhi (325km).

Where to stay: Hotel Ros Common (Rs 1,550-2,350; 01792-272005) is a lovely old bungalow converted into a comfortable six-room hotel by the HPTDC. Glorious view, laidback but friendly service, and great chicken sizzlers.

Hotel Alasia (Rs 1,650; 272008) is old and atmospheric, though the lawn looks rather sorry for itself and the old games room hasn’t recovered from a fire a few years ago. There’s an almost-Victorian carpeted lounge complete with a piano, and functioning fireplaces in some rooms.

Hotel Anchal (Rs 400-1,200; 272542) is located at the end of the Lower Mall, Anchal and its competitor Gian provide options for budget travellers. Basic, clean rooms with attached baths. The incredible ‘family suite’ sleeps eight and has its own balcony overlooking the valley.

What to eat: Eat a bun-sum (a hot samosa stuffed in a bun) at Narender Singh’s shop in the bazaar. If you’re feeling intrepid, try his other ‘special item’ — bun-gulab jamun (“Woh jam jaisa ho jata hai,” offers its inventor). Try the Daily Needs burger, with its peppery ham and perfectly toasted caraway-strewn bun (tell them to go easy on the ketchup). Definitely stop by the chai shop at the end of the bazaar for a plate of pakoras in the evening — superb by any standards.