For years now, as Shanghai prepared for the largest world fair ever, those of us who live here have had to put up with buildings wrapped in bamboo renovation scaffolding. We have sighed at paint-spattered sidewalks—when there was a sidewalk at all. Often, the pavement itself was ripped off for replacement. Massive chunks of the city were boarded off to accommodate the pile-drivers, and clouds of construction dust choked us as subway lines were added. The historic waterfront Bund was closed off and inaccessible as jackhammers flew over a new promenade.

More recently, sidewalk hawkers were chased off the streets. Our pirated-DVD store managers now beckon us through hidden backdoors where the real selection is kept. Haibao—the blue water-blob who is the Expo symbol—was installed as a metal statue in my neighbourhood park. Expo volunteers in orange jackets appeared all over the city, looking slightly self-conscious. Every Shanghai citizen was promised a free ticket. To our delight, a fleet of shiny new Expo taxis hit the roads, the seats squeaky (and with seatbelts!).

Then, on May 1, all the city’s wraps came off. The dignitaries flew in and Shanghai, tarted up and gleaming, grinned from ear to ear as it stepped onto the world stage amidst a burst of fireworks over the river.

On 5.28 sq km, on both sides of the Huangpu river—Shanghai moved thousands of families and an ancient shipyard to help make space for this—around 200 countries and 50 government and non-government bodies have built pavilions to showcase their best.

On this same river, some 170 years ago, sailed Britain’s emissary Henry Pottinger, armed to the teeth and backed by gunboats. The Qing Dynasty sued for peace and China and Britain in 1842 signed what the Chinese call the ‘Unequal Treaty of Nanjing’. The treaty never once mentions the word opium, or profit, but it secured by force for the British the right to live and trade in Shanghai and other port cities, thereby facilitating access to China’s lucrative markets. The French and the Americans quickly followed.

China never forgot the Opium Wars. Along with the Japanese occupation of China just before World War II, they remained festering scars on a national psyche. “The Expo is a repudiation of that humiliation of a semi-colonial history,” said photographer Liu Heung Shing, who has just released a collection of pictures of Shanghai to coincide with the Expo opening.

It’s not a history that young Chinese know or care much about, but the Expo is definitely a site to impress a date. This is their city, this is their time and it is their eyeballs—as affluent, future world travellers—that the world has come to Shanghai to attract.

The French (who have retained their canny sense of China) were first in line to accept a spot. The Americans (who have not) were last. The Expo forecasts 70 million visitors for the six months that it’s running: that’s an average of about 380,000 people a day. “Most of those will be school children trucked in from the countryside during their summer holidays,” said one journalist friend.

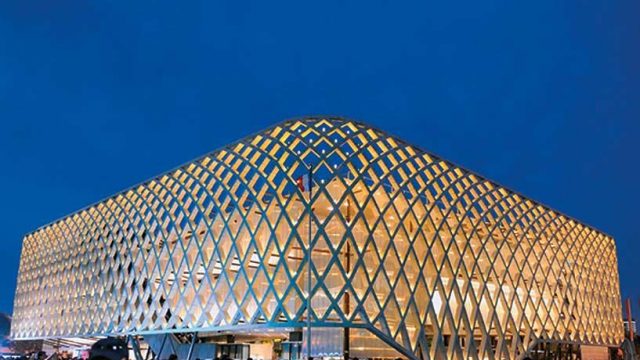

Whatever the case, the Expo feels exactly like what it is: a mela, a maidan, a place to delight and make you gasp. Which is what my husband and I did—middle-aged and jaded as we are—gliding up the escalator on our first visit, having found our way there on a brand new subway line and swept through empty security checks. We happened to swivel around and there rose the massive, elegantly simple China pavilion painted a brick shade that some call ‘Forbidden City red’. The structure is built using interlocking wood brackets, a 2,500-year-old traditional Chinese technique that requires no nails.

We never made it inside the popular pavilions (China tops the list)—you need reservation tickets that are handed out at the beginning of the day. Tens of thousands are snapped up in the first five minutes. Hanging over the event, like so much powdered saccharine, is the contagious feeling of goodwill generated when 200 countries get together and do something other than quarrel.

For the largely Chinese crowd thronging the Expo, this is an incredible opportunity to see the world without leaving home, and one senses a certain teeth-clenching determination to see it all—understandably, because national treasures and visiting foreign dignitaries litter the Expo grounds like confetti.

Egypt has just unveiled a statue of the Pharaoh Amenhotep IV, one of its eight national treasures. The monarch of Brunei just dropped in to see his pavilion. Dutch royalty is rumoured to be in town shortly.

The Danes sent over their mermaid, because, as they said, they wanted to send what they loved the best. There she sat, after her long, ignominious journey via cranes and crates and customs, looking a little lost with no sea to look at, slightly hunched, her tail tucked under her bottom. “Denmark is a land where we don’t pray very much, but that is OK, because we believe in each other,” was the cryptic message to China from one Stine Spedsbjerg, a Danish writer.

Israel proudly displays two pages of the original manuscript of Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (donated to the Hebrew University by his wife).

The French have lent the Expo some masterpiece paintings, including ‘The Dance Hall in Arles’ by Van Gogh and ‘Woman with Coffee Pot’ by Cézanne.

India brought out Rabindranath Tagore — almost literally I thought, doing a double take in the afternoon sun at a man in a kurta and long white beard. There was a celebration of the 149th birth anniversary of our poet. Tagore came to China three times to lecture. He said he might have been Chinese in a past life, because stepping off the boat onto Shanghai’s soil felt like coming home. He garnered quite a following amidst the local literati, but not without controversy; the more ardent followers of the then newly born Chinese Communist Party needed hard-headed youth for the Revolution. They thought Tagore might soften them with all that mystical nonsense.

On a warm May afternoon, at the India Pavilion, the largely Chinese crowd sat through speeches. There was the usual mike-tapping, thanks to reliable action from the Ghost Who Lives in Microphones At All Indian Functions. A Chinese actor read out poet Zhao Lihong’s rather lovely ode to Tagore, ‘Have You Seen My Heart’. He read with his palms held up, with some dramatic pauses, a certain amount of furious blinking and staring into the middle distance. But it worked. The performance wound up with an affecting, simple dance by a Bengali troupe, the choreography set to Tagore’s music. Several hundred Chinese, sitting on bamboo seats, hanging over the rails outside or passing by, stopped to watch spellbound or take pictures.

The winners at this Expo are music and dance, the most primeval forms of animal expression that need no language. Shashi Tharoor was right. Forget the treaties and the summits—art is the strongest bridge between cultures. They have certainly provided my best moments at the Expo so far; when dusk softens the sky, the buildings light up and you can wander the grounds cradling, say, an authentic Czech or Danish beer, taking in a concert of Turkish music, or the thrilling thunder of lithe Korean drummers, or the lilting melodies of a Maori choir.

I walked into the Indonesia pavilion, in search of childhood sensory markers and just then, with a marvellous synchronicity enhanced by a vodka-fejoa-apple cocktail purchased from the New Zealanders, the Gamelan orchestra launched its haunting, groaning bells. Three little Balinese girls strutted onto the stage, their frangipani flower horns all aquiver, their eyes flashing up and down, their heads nodding from side to side, fingers aflutter. They were perhaps 10 or 12 years old, but in the blue wash of stage lights, wrapped in the music, they were warriors and queens. They were alarmed, or despondent, or pensive or wrathful. I couldn’t tell which story they were enacting, until one little dancer came on with wings strapped to her forearm, and I slapped my forehead. Jatayu! It was a marvellous reminder that we have been borrowing from each other for thousands of years anyway.

The other big-draw pavilions are the Western countries. The British pavilion—a sea anemone type structure made of plastic tubes filled with seeds from around the world—is a biodiversity project. The Saudi pavilion too attracted a massive line, which we joined out of curiosity, snaking around the barrier meant to keep people in order. We fell into half-conversations and asked the man in front why he wanted to see the Saudi Pavilion. “They’re rich,” he said. “Thought we’d go have a look.”

After an hour, we lost patience and left to go look for some alcohol, thereby missing the key Saudi sight, as described on the website: “The world’s largest curved screen covering 1,600 square metres. Visitors standing on a moving belt—like a flying carpet—to watch a 15-minute special-effects movie that makes them feel as if they were flying over the country’s deserts and cities.” The persistent folks win: a few hours in a line to see a pavilion is nothing next to an expensive flight and jetlag.

To facilitate their visits around the Expo, elderly Chinese carry around three-pronged walking sticks with an extension that doubles as a stool. People come with bags stuffed with edibles. We saw one thrifty woman who wheeled a bag filled with food so she needn’t spend extra money on eats and could spend the whole day at the Expo—the bag had a folding chair attached to it.

The Expo requires much walking, but there are drinking water fountains aplenty, of all heights; and abundant clean toilets that flush and have toilet paper supplies. There are Starbucks and signature Shanghai restaurants selling hot noodles. The pavilions have their own food too.

“The Expo 2010 will enhance the friendship and exchanges among people worldwide,” Yang Xiong, executive vice-mayor of Shanghai, said at the opening flag-raising ceremony. This might be irritating policy speak, but it’s hard to refute when you see two Chinese farmers with lines on their faces, dirt under their nails and greying hair, lean forward in awed stillness to watch a Jordanian artist fill coloured sand into a bottle.

I’m eager to go back to the Expo (I’m sure I will go multiple times over the next six months) and see what the urban innovations on display are—this is after all the Expo themed ‘Better City, Better Life’, and the idea is to feature inventions and marvels. I’ll also catch the next concert—Herbie Hancock features at the US pavilion.

Some people have more immediate concerns. Rahman Nazar, at the Afghanistan pavilion—where stalls are crammed with carpets and other Afghan handicrafts—complained that the Chinese were not buying his wares. Nazar is a tall, well-built man, with a thick moustache and an easy manner who had travelled here from Kabul. “They just take pictures standing next to me. The young, the old, men, women, as though Shah Rukh Khan had come,” he said in Hindi. Everyone is taking pictures, because this is a summer to remember. Drivers get in trouble for stopping on the soaring Lupu Bridge to take pictures of the Expo site from a height, thereby creating massive traffic jams.

Just as in the 18th century, the world still needs China’s buying might. But the power equation has evened out. There’s plenty of security, but not a gunboat in sight. And this summer, I’m going nowhere because the party’s in Shanghai.

Open until October 31, 2010. Visit http://en.expo2010.cn/.